Victoria’s new Phonics Plus lesson plans are being rolled out to support early literacy instruction. But do they actually enhance early reading instruction? As a lecturer dedicated to preparing future teachers, I have serious concerns about the quality of instruction they promote.

I emphasise the importance of research-based practice—my students create literacy lesson plans and justify their instructional choices with evidence. But where is the research backing these lesson plans?

The Victorian government promotes Phonics Plus as a way to enhance early reading instruction, focusing on phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, handwriting, and morphology. To support its implementation, the government has provided lesson plans for teachers. Although not mandatory, these plans set the standard for classroom instruction and warrant closer scrutiny.

Are These Lessons Too Long and Too Rushed?

How long might you expect young children to sit and engage as a whole group? Lesson length and sequencing are important considerations. Each lesson requires Foundation students to sit through a 25-minute Phonics and Word Knowledge session—a demanding duration for young learners, especially when tasks require sustained attention and cognitive effort.

A closer look at the sequencing raises more concerns. For example, in Phonics Plus Set 3: Lesson 9, activities jump from syllables to phonemes. Clapping syllables is a whole-word awareness task, immediately followed by phoneme-level analysis requiring segmentation into individual sounds. This shift from recognising larger spoken chunks to identifying separate sounds demands a significant cognitive leap that would even confuse adults.

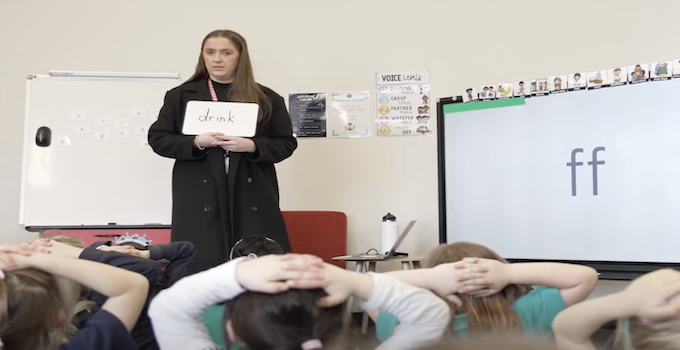

The Phonics Plus lesson demonstration video on the ARC website reinforces these concerns. The scripted, rapid-fire teaching style, delivered from the front of the room, shows little to no scaffolding for students navigating these concepts.

Cognitive Load Theory emphasises the need for clear, step-by-step scaffolding over rapid shifts. Additionally, the National Reading Panel found that phonemic awareness instruction is most effective when focused and not overloaded with multiple overlapping tasks.

Where’s the Differentiation?

These lessons follow a ‘spray and pray’ approach, treating all students the same regardless of ability. For example, the high-frequency word ‘at’ appears in Lesson 1 as new content for all students. What happens if some children can already recognise and read this word?

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development highlights the importance of tailoring instruction to students’ current abilities—too easy, and they become bored; too hard, and they become frustrated. Bruner also emphasised scaffolding as essential for ensuring students build on existing knowledge rather than receiving one-size-fits-all instruction. Snow, Griffin and Burns stress the need for differentiated literacy instruction, particularly in early years classrooms. The evidence is clear: without differentiation, capable students risk disengagement, while struggling students are left behind.

Fluency Without Meaning?

Another area of concern is the use of texts to build ‘fluency.’ In Phonics Plus Set 1, Lesson 3, the Fluency Text is simply a grid of single letters: A, T, and S. The lesson plan directs teachers to use choral reading and partner reading of this text for 15 minutes.

In Lesson 9, students engage in choral reading using:

Tom can tag Sam and Pat.

Tom can tag Sam at the dam.

The cod is in the dam.

These texts align with phonics instruction but lack narrative value. How can students meaningfully engage with them?

Fluency is not just speed and accuracy but also expression, pacing, and comprehension. The lack of meaningful context in these choral reading tasks suggests students are practising letter and word recognition in isolation rather than developing expressive, purposeful reading.

Choral reading might seem effective, but research suggests otherwise. Shanahan (2024) argues that choral reading does not inherently improve fluency because it focuses on group reading without individualised pacing or comprehension engagement. Kuhn & Stahl (2003) found that fluency is best developed through repeated reading with feedback and discussion about meaning, rather than rote repetition of sentences.

Have you ever sung along to a song only to later realise what the lyrics actually mean? Just as choral singing doesn’t guarantee comprehension, choral reading doesn’t ensure students make meaning from text.

What About Meaning-Making?

Perhaps the most pressing issue in Phonics Plus is the lack of emphasis on meaning-making. Young readers thrive on content-rich texts that foster discussion and comprehension. While decodable texts reinforce phonics, they must be complemented by experiences that promote storytelling, prediction, and interpretation.

Duke and Pearson found that effective reading instruction integrates both code-based and meaning-based approaches. Castles, Rastle & Nation (2018) also advocate for balanced reading instruction embedding phonics within engaging and meaningful reading experiences. The Simple View of Reading reinforces that reading involves both decoding and comprehension—without explicit attention to meaning-making, fluency practice lacks purpose.

Prioritising rapid decoding over comprehension mirrors the shallow processing seen in digital reading, undermining critical literacy. Is this the outcome we want for our students?

Concerning gaps

While Phonics Plus aims to support early literacy, its lesson plans reveal concerning gaps in differentiation and comprehension development. Victoria’s reading reforms must balance phonics with meaningful reading experiences to develop engaged, proficient readers. Unless these gaps are addressed, the lesson plans risk doing more harm than good.

Naomi Nelson is a lecturer and literacy coordinator at Federation University Australia’s Mount Helen Campus. She educates pre-service teachers and works with colleagues to deliver contemporary and engaging literacy courses. Naomi’s PhD research investigates reading comprehension, the impact of reading mode (paper vs. screen), and the strategies students use to understand text.

The header image is a still taken from Phonics Plus In the Classroom, a video from the Department of Education, Victoria