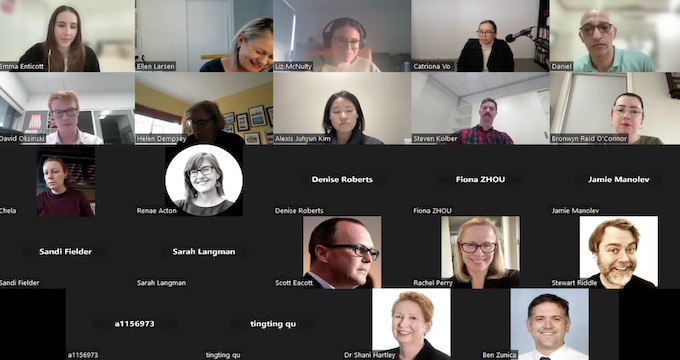

We’d like to thank those Early Career Teacher Panellists on the Teachers’ Voices : Catriona Vo, Emma Enticott, Liz McNulty, Daniel Siddhartha, Alexis Kim, David Oksinski

As educational researchers, we must listen to the voices of teachers to understand what research is critical to their work, and how we can effectively work with teachers to respond to contemporary issues and opportunities of the profession. Educational research operates in a void when teachers’ voices are left unheard. That void constrains the critical professional partnerships needed to bridge the research-practice divide and produce research with an authentic and powerful connection to educators’ work.

The Australian Association of Research in Education (AARE) Teachers’ Work and Lives Special Interest Group launched the first in a Teachers’ Voice Panel Series on June 24. It provides time and space for educational researchers to listen to teachers about what research matters to them. In this initial panel, six early career teachers from state and independent schools across Queensland, Victoria, the Northern Territory, and New South Wales came together online to share their ideas about research and their work. We asked our panel the following questions:

What are the current topics or issues for you as an early career teacher that are critically important for educational researchers to be investigating right now?

These early career teachers showed a clear and strong commitment to their professional growth. They indicated they were most interested in learning how best to meet the needs of the diverse students in their classes.

“How do we as teachers engage in culturally and linguistically responsive teaching? Given the diversity in schools and just how our classrooms are growing in terms of how diverse they are.” – Catriona

“Inclusive education… I’ve got anyone and everybody in my classroom, so what kind of research can be done so that students can get individual attention, and [teachers] giving each student exactly what they need.” – Liz

Inclusive practice

Inclusive practice and culturally responsive pedagogy emerged as topics of crucial importance, highlighting the focus of these future educational leaders on acknowledging, celebrating, and responding to the richness of their classroom cohorts.

They also spoke to their pressing need to understand how to work with Artificial Intelligence in ethical and practical ways.

“AI is another big thing. It’s taking over; whether its students using it to plagiarise (so how might we design tasks that stop this), or, how we might find ways to use it in responsible ways”. – David

The rapid evolution of digital technologies made the need for future-focused educational research in this space time-sensitive. Emma said: “Technology is moving so fast . . . I feel like the research that’s coming out now is delayed to my needs.” Panel members’ responses underscored the significant role that early career teachers will play in leading the way in working with a rapidly evolving digital landscape.

The panel also pointed to the potential for research to inform how teachers work together to innovate and collaboratively build professional capacity.

“To me, workplace culture is what it’s all about, genuine collegiality, with a generative outlook toward how to improve systems”. – Daniel

Still COVID-19

Interestingly, the residual impact of the COVID-19 years still loomed large as they discussed their need for research that could contribute to their address of student resilience, seen as an ongoing concern among students in the classroom.

“A lot of the younger students are coming out of the COVID years lack resilience. So it would be good to have more research into how we can support students with less resilience, especially with the limited resources we have”. – Alexis

We were impressed by the varied suite of topics reported by the panel as mattering to these early career teachers. At the heart of their interests was a commitment to social justice, a responsiveness to contemporary digital challenges, and a desire to contribute to a work culture of collegiality and collaboration.

To what extent do you, as an early career teacher, currently connect with research and/or researchers as part of your work? What are the available opportunities/challenges to doing this for you?

As with anything teaching, the “T word” loomed large as the key challenge to connecting with research and researchers.

“Time is a resource we don’t have much of, and I find that reading research can be quite difficult, it can be quite dense, but through reading groups and discussion this reading can be a lot more beneficial.” – David

Time alone, however, is not the only barrier to being research-connected as an early career teacher. The panel also shared how access to research post-graduation is also hindered when connections to their university are severed.

“Once I left university, of course, I have my alumni account, but that’s very restricted in terms of what I can access. So, I’m only often getting outdated information or I’m only ever getting the abstract.”- Emma

It was a theme that most of the early career teacher panel were primarily engaging in research through Professional Learning opportunities, with many of these opportunities being limited due to funding and time constraints. These systemic barriers to engaging in research, combined with the “density” (David) of research in some instances, led to the panel raising the need for “bite-size” research summaries on a variety of accessible platforms like practitioner journals, LinkedIn, and Instagram etc.

The diversity of ways that early career teachers preferred to access research-related media was also notable. with some noting preferences for print media (“the value of grabbing a physical text that is sitting around the staffroom”- Daniel) and others accessing videos and digital media more frequently.

For us as researchers, this raised thoughts of how we keep early career teachers connected to research and the universities they have spent so much time in after graduation. This appears to be an important question in moving forward in continuing to bridge the perceived research-practice gap.

As an early career teacher, what kind of research would you be most likely to take part in? How would you suggest we bridge the gap between the research community and the early career teacher community?

Many early career teachers leaned on the university-to-school connection during their first years of teaching, with a large portion of the connection to research coming from direct contact with past lecturers.

“The connection with lecturers and when you leave university, I think those relational connections are just so important for sustaining us as teachers sometimes just having that person that we can talk to, to say, “Hey, you know, this is going on in our classroom, do you have any thoughts about this” or just even checking in.” – Catriona

Emma too explained how she drew on her connections with past teacher educators. She proposed preservice teachers before graduation need to be upskilled in how to stay connected:

“It is a skill- staying connected. How do we stay connected? What are some really quick and easy places we can go to get this research? In that final year of ITE, how can we teach graduates how to stay connected and where to go for help”- Emma

They want access to research and are happy to be part of research

As well as these university-teacher connections providing a means of access to research, the panel also showed interest in being part of educational research while being cognisant that such research would need to work in with their everyday work.

“If I was part of research in my school, something that sat alongside my work, then that is something that I would be interested in”- Alexis

Excitingly, they encouraged educational researchers “to do a lot more research with their students who have gone out into teaching” (Daniel), reminding us that our alumni are important research partners.

The early career teachers on this panel, however, understood the important role that teachers played in being open to the value of research.

“There needs to be a shift in how teachers actually think about research…so how can we make research seem like it is accessible and approachable and that it is a part of everyday teachers’ work? Until we unpack that position that teachers may have about research and all those assumptions that teachers may have, that will go a long way to bridging teachers and research and how we design research that will get teachers onboard and involved in research too” – Catriona

As educational researchers, we need to find ways to connect with our early career teachers in ways that create manageable and timely access to cutting-edge research that can support their work.

Ways to connect

“This panel is an awesome starting point and I have learned so much this afternoon and that just speaks to the importance of these kinds of discussion.” – Liz

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to these early career teachers for their time and insights. The convenors of the Teachers’ Work and Lives SIG, along with all participants in this event were left in no doubt that the future of the profession is in very good hands!

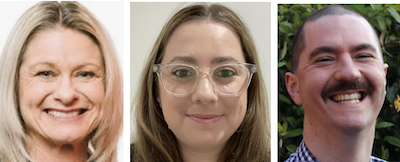

From left to right:

Ellen Larsen is a senior lecturer in the School of Education at the University of Southern Queensland (UniSQ). Ellen is a member of the Australian Association for Research in Education [AARE] executive and a convenor of the national AARE Teachers’ Work and Lives Special Interest Group. Ellen’s areas of research work include teacher professional learning, early career teachers, mentoring and induction, teacher identity, and education policy. She is on Twitter @DrEllenLarsen1.

Bronwyn Reid O’Connor is a mathematics educator and researcher in the Sydney School of Education and Social Work at the University of Sydney. Drawing on her experience as head of mathematics, Bronwyn teaches in the areas of secondary mathematics education at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Her research focuses on supporting students’ motivation, engagement, and learning in mathematic as well as secondary mathematics teacher education. Her work focuses on addressing the research-practice nexus, and she serves as Editor of the Australian Mathematics Education Journal to continue disseminating high-quality research to practitioners.

Steven Kolber is a proud public school teacher who has been teaching English, History and English as an additional language for 11 years. He has been recently named to the top 50 finalists in the Global Teacher Prize. He is passionate about teacher collaboration which he supports through organising Teach Meets, running #edureading (an online academic reading group) and supporting Khmer teachers by leading teacher development workshops in Cambodia with Teachers Across Borders Australia.

Header image from the Teachers’ Voice Panel Zoom call.