Video games are a dominant form of entertainment, consistently outselling books, film, and music combined. How can education learn from their addictive design?

Great games and great learning share attributes of experiences that challenge us through a variety of immersive problem solving, decision-making and strategic activities.

Video games tap into supportive internal factors of learning such as engaged and positive emotional states, immediate feedback, interval learning and input quantity (or ‘chunking’).

It’s super effective! (For learning)

The success of video games in facilitating learning lies in their intuitive, pleasant design, engaging narratives, and addictive, rewarding feedback loops. Research indicates that video games can improve perception, memory and knowledge retention.

Though video games may be studied as texts , we are focusing here on incorporating game-inspired elements into teaching methodologies to enhance both learning outcomes and student enjoyment. By leveraging the intuitive and self-directed nature of gaming, educators can make learning addictive and engaging across various subjects.

Gamification vs games-based learning. Fight!

Incorporating game elements into education can take two primary forms. Both approaches can enhance the learning experience by adding elements to lesson content such as risk and excitement, urgency, pleasure, and status.

Gamification pervades our lives in everyday things such as loyalty program points, fitness apps, productivity performance targets, Uber ratings, social media metrics and dating apps. Gamification in education involves integrating game mechanics, such as points, badges, achievements, awards or rankings to the classroom, while game-based learning uses actual games as the primary teaching tool . Here, we are more focused here on game design than using games per se.

“It’s-a-me, Mario!”

Effective game design is crucial for facilitating learning through gameplay. Games with visually pleasing designs, engaging narratives, and addictive gameplay mechanics tend to be more successful in capturing learners’ attention and promoting active, enjoyable participation.

Engineer Mark Rober outlined how a game design approach, what he calls the “Super Mario effect ” can encourage participation in learning activities where it otherwise would not be evident.

By situating repeated, instant feedback for error correction in a dynamic narrative or context where there is a freedom to fail, gamers learn from failure, try alternate strategies, and develop their skills at their own pace until they succeed.

Design is crucial to this process, and there is even a New York school that has based its philosophy on the principle of video game design.

Achievement unlocked

Video games excel in setting challenging goals and providing clear objectives for players to achieve. The sense of accomplishment and progression inherent in games motivates players to overcome obstacles and master new skills.

Educators can adopt similar strategies to set challenging yet achievable goals for students, fostering a sense of accomplishment and motivation in their learning journey.

Emphasising effort, progress, and continuous improvement fosters a sense of agency and ownership in learning.

Advocates of game-based design have recognised that games prove students are quite capable of memorising and recalling immense volumes of knowledge, when it is constructed by them and founded in experience.

Pokémon players famously memorise more than 27,000 values in three dimensions when battling hundreds of character iterations. By contrast, the entire periodic table has 118 elements and there are approximately 200 irregular verb forms in English.

While students may want to hide their effort and achievements, gamers proudly share their status, achievements and even how long it has taken. In Mortal Kombat, one achievement requires winning 2,800 matches, playing more than 670 hours. To obtain the Pure Poker achievement in Pure Hold’em takes about 10,000 hours.

One has to respect the time and effort gamers dedicate to their craft. Gamers are willing to dedicate and invest time into seemingly repetitive and mundane levels or challenges, showing a persistence and resilience that we would envy in education. Some gamers even modify their games or set challenges to make them even more difficult than the developers intended, such as speedruns or completing games using only one button!

Games are ‘eustressful’, a beneficial form of stress somewhere between fun and scary, that is motivational.

How can education manage this balance? Measuring progress rather than purely achievement could be key.

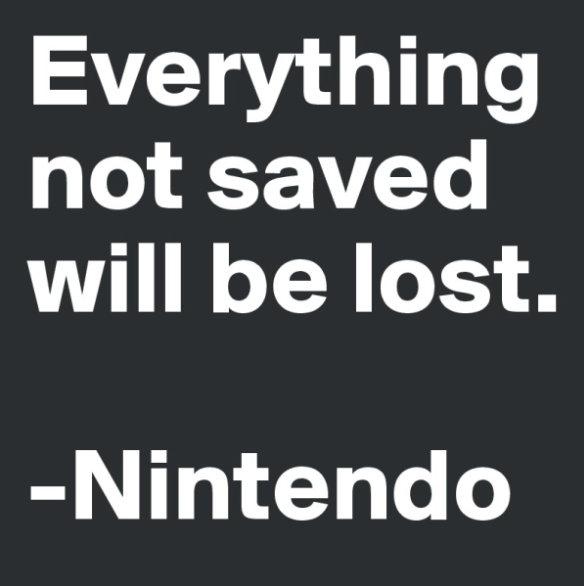

“Save progress?”

Games offer tangible feedback on players’ progress through various metrics such as scores, levels, and achievements. Similarly, educators can implement assessment methods that provide meaningful feedback and recognize students’ growth and achievements. Emphasising progress over final scores encourages continuous improvement and resilience in learning. ATAR, take note!

The Legend of Zelda was one of the very first games to offer saving. In education, resubmitting a task for a better grade and measuring improvement rather than pure achievement is an example of offering the equivalent of save points for assessments. Could a student’s response to teacher feedback be considered as well as the achievement itself?

Compared to many games of the 80s and 90s where a player had only a few ‘lives’ to survive the whole game, modern first-person shooters such as HALO and the Lego series of games provide more generous opportunities to make progress and complete levels, rewarding persistence and removing a punishment for failure. Where once, players may have merely given up when reaching a level or ‘boss’ that was too difficult, modern games allow players to eventually progress. When learners are not as worried about how they fare relative to everyone else, they focus on their own game.

“Select your difficulty”

Games often offer adjustable difficulty levels to accommodate players with varying skill levels and preferences. The 1977 Atari is credited as one of the first video game consoles to offer selection of difficulty.

Nintendo intentionally made Disney’s The Lion King and Aladdin games difficult so that gamers would have to rent the game longer from the video store!

Games showcase a stellar array of ways to increase challenge in differentiated ways. They can add more enemies, more difficult or faster enemies, more complexity, reduced health or time to complete the same challenge, and even adaptive intelligence enemies.

Moving away from kill counts and mindless shooting, first person shooter action games such as the James Bond franchise and Metal Gear Solid have innovated with objectives related to time, stealth, lives lost, civilians saved, accuracy, ammunition saved and even style.

Similarly, educators can personalise learning experiences to meet the diverse needs of students by offering differentiated instruction and support. By providing opportunities for students to challenge themselves while maintaining a supportive learning environment, educators can foster a sense of competence, growth and autonomy in their students.

“Game over. Play again?”

Often based in an immersive world or context, in games there is a clear sense of objective made meaningful by a narrative and the presentation of a pathway towards a goal. The map views of SuperMario, Donkey Kong Country and Candy Crush are exemplary examples of how to establish a sense of journey and incremental challenge, which promote mastery and replayability.

By embracing game-inspired elements such as dynamic feedback, meaningful challenges, and personalised learning pathways, educators can empower students to become active participants in their learning journey.

Video games offer valuable insights into effective learning strategies that educators can leverage to create engaging and immersive learning experiences.

Dr Hugh Gundlach is a lecturer and researcher in the Faculty of Education, The University of Melbourne. He teaches in the Master of Teaching (Secondary) and is the Commerce Coordinator.