Read our full paper on lead teachers here.

Australia needs to recruit, develop and retain high quality teachers – lead teachers. To make that happen, this country needs a more credible, economically affordable, administratively feasible and legally defensible professional certification system for leading teachers. That’s not all. It also needs better rewarded career pathways for the teachers that meet the standard in Australia.

The National Teacher Workforce Action Plan released by education ministers last December identified the pivotal role our national system for the certification of Highly Accomplished and Lead Teachers (HALT) could play in ‘elevating the profession’. The plan sets a target for the certification of 10,000 teachers as HALT by 2025.

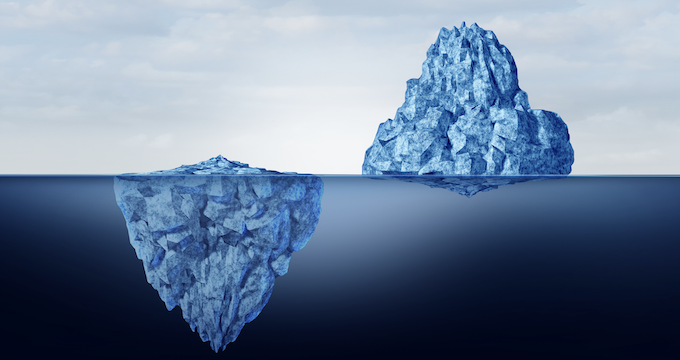

But in the 10 years since HALT certification was introduced, only 1,200 teachers have so far gained certification – representing less than half of one per cent of all 307,000 full-time-equivalent teachers in Australia.

What’s putting teachers off?

Deficiencies in the certification process are a key reason for the low uptake. The process of providing evidence for each of the 37 indicators was cumbersome and inefficient, leading significant proportions of applicants to drop out. Assessing applications was also time consuming and therefore expensive.

The current approach is burdensome and costly. The plan calls for the streaminling of HALT certification processes. States and Territories are being asked to develop their own processes that are ‘less onerous, while being rigorous’, and guided by AITSL’s revised Framework for the Certification of Highly Accomplished and Lead Teachers.

Streamlining needed but not enough

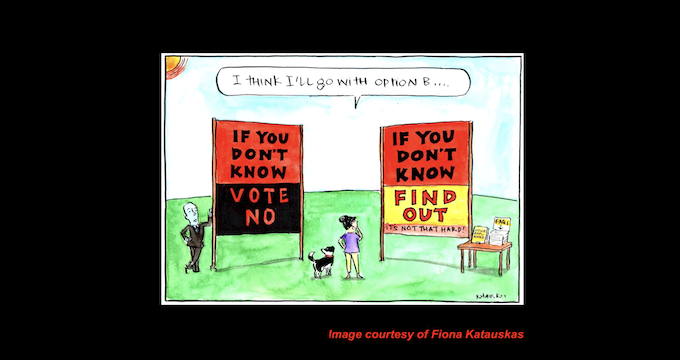

Developing rigorous methods for standards-based assessment of teacher performance is a highly complex measurement exercise. Tough questions will inevitably arise about a certification process’s ability to reliably distinguish between teachers who have attained the HALT standards and those who have not.

International experience shows that certification systems live or die to the extent that stakeholders are confident about their validity and reliability. The revised AITSL Framework covers matters such as eligibility, portability and appeals processes but does not describe the methods Authorities are to use for assessing applications.

Streamlining the HALT certification process would be greatly helped by the development of an assessment framework that gives applicants a clear indication of the evidence they will need to prepare for certification and how it will be assessed.

What’s the solution?

In a pilot conducted from 2015 to 2018, the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) developed assessment frameworks for highly accomplished primary teaching and secondary science teaching.

These assessment frameworks are freely available. Each includes four portfolio tasks with detailed guidelines. Together, they enable applicants to provide evidence covering all 7 of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers and a representative sample of teaching skills across the curriculum they teach.

To illustrate, most primary teachers are expected to teach English, Mathematics, Science, Humanities and Social Sciences. For English a primary teacher might choose to document a unit of work in which they planned to:

‘engage students in writing for a range of purposes and audiences, catering for the diverse learning needs of students in planning classroom activities and enabled all students to make progress in their knowledge and understanding of writing.’ (Australian Curriculum ACELY1694)

This statement from the Australian Curriculum provides a clear indication of what an applicant needs to demonstrate in a portfolio entry. It matches what accomplished teachers do in the normal course of their job. How a teacher does this is for the teacher to decide.

Evidence of impact

As with all the portfolio entries we developed, this task calls for evidence of impact on what students are doing and learning. As teachers prepare portfolio entries evidence prospectively once they decide to apply for certification, not retrospectively, these tasks also provide a valuable vehicle for professional learning. Similar assessment frameworks can be developed for other subjects and levels of teaching.

At the end of the pilot, between 81% and 100% of participating teachers positively rated the clarity, validity and fairness of the portfolio tasks. All agreed that preparing their application was a valuable professional learning experience that improved their teaching.

Importantly, we found that assessors took about one hour to judge each portfolio entry. Four entries would take no more than 4 hours. That’s significantly less than the time it now takes for assessments of each application.

Making certification mainstream

Under the current Plan, the goal is to increase the number of teachers certified as HALT from 1,200 to 10,000 by 2025. This is a modest but realistic goal in the short term. Long term, however, far more ambitious goals will be needed if the Plan is to have a significant impact on recruitment, retention and the quality of teaching.

Over the next 15 to 20 years, we should aim for a situation where most teachers and school leaders now progress through certification as a normal part of their career pathway to higher salaries and school leadership positions. Only then can certification hope to increase the recruitment of high-quality graduates and the retention of experienced and accomplished teachers in the profession.

Dr Lawrence Ingvarson, AM, FACE, is internationally recognised for his research on teacher education, professional development, teacher quality, teaching and leadership standards and assessment of teacher performance and has published widely in these areas. He is a Fellow of the Australian College of Educators. He joined ACER in 2001 and served as research director until 2006.

Dr Hilary Hollingsworth is a co-research director at the Australian Council for Educational Research and has worked both nationally and internationally, as a university lecturer, education consultant, teacher and as a researcher in the fields of teaching quality, teacher and leader professional learning and teacher standards. Her current work is strategically focused on enhancing and shaping teaching, learning, and school leadership policy and practice.