Let’s face it, it can be fun to poke holes in the premise of silly Hollywood films. The idea that a character portrayed by Scarlett Johansson has tapped into the 90% of her brain we don’t use provides a basis for glossy action set pieces but isn’t founded in reality. Research in neuroscience does not support the idea that we only use 10% of our brains.

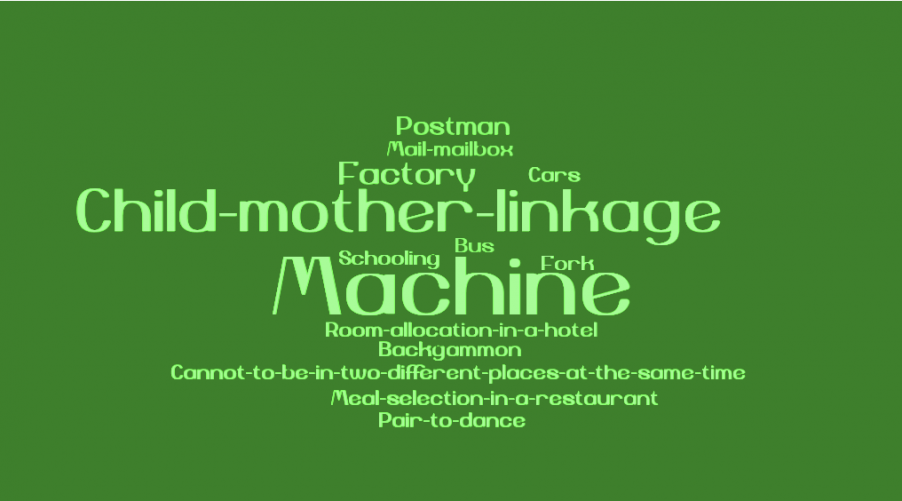

The recently released discussion paper from the Teacher Education Expert Panel recommends that initial teacher education students in Australia learn about ‘how the brain learns and retains information’ and are inoculated against such neuromyths. These include the idea that people are ‘left-brained’ or ‘right-brained’ or that students should be instructed in their preferred modality-based learning style.

During the last few decades, neuroscience has uncovered more about the inner workings of our brains than in the entire recorded history prior to this time. New imaging technologies have unlocked many of the mysteries of the enormously complex machinery in our heads. These discoveries have led to major breakthroughs in the treatment of numerous disorders and promise many more. The research has also provided deep insight into what’s going on in students’ heads when they are learning. This is all undisputed.

However, as the cliche goes, it’s a long way from neurons to the classroom. The notion that a working knowledge of how the brain functions (or doesn’t) is immediately useful to the day-to-day work of teachers is flawed. We found no clear relationship between the level of knowledge about the brain and how effective teachers are. Neuromyths in education are themselves a neuromyth.

It isn’t through an understanding of the brain that most of the useful basic research on learning comes from. Rather it is research on the mind (I’m not going to get into the relationship between the two, which has been a topic of fierce debate since Descartes). The most impactful basic research on learning is often from the learning sciences, particularly psychological science.

The biological level of understanding learning is important in its own right. However, it is mostly through controlled studies on attention, memory, emotion, and metacognition, among other factors, that we can dismiss some potentially harmful ideas about learning and point us in more productive directions. That there is a correlation with some now observable parts of the brain is less important and often not useful.

For example, studies on the mind provided the evidence to debunk the learning styles myth. Not having to consider what to do about the kinesthetic learners in my classes when I’m designing lessons is useful to me as a teacher. That students are using all their brains in my class (or not) is less so.

Does it really matter whether the emphasis here is on the brain or the mind? It is, after all, useful to know about some aspects of neuroscience to prevent being sold on ideas such as brain training, that have no empirical basis. There are problems that are perpetuated by overemphasising the brain. These include but go beyond people using neurobabble to sell questionable products and approaches.

Focusing on the brain perpetuates an overly reductionist notion of basic research on learning. Much of the criticism levelled at the learning sciences more broadly is associated with the supposed positivist nature of the research. Through the control of factors in search of causal relationships, the work is far too removed from the complex environments that students learn in, so the argument goes. The emphasis on the brain does not help with these criticisms. Reducing learning to biological processes is inherently reductionist.

There is undoubtedly a role for basic research to inform education. What we do in the classroom should be informed by rigorous evidence of causal factors. Cognitive Load Theory, Multimedia Learning Theory, and research on self-regulated learning are all critical contributions to improving what we do in physical and virtual classrooms. All have a foundation in basic research on the mind. These are just some of the many examples. The ongoing challenge is to figure out how basic research translates to practice.

While foundational research is useful and needed, it can’t be applied in a prescriptive way. One of the other major criticisms of the role of basic research on learning for education is that the work de-professionalises teachers. This argument is perhaps best captured in Gert Biesta’s notion of ‘learnification’.

It was once the case that people like B.F. Skinner were convinced that basic research could provide the recipe or formula to ‘fix’ education. These strongly positivist notions were largely abandoned in the late 20th century (with perhaps some notable exceptions including some technology companies and consulting firms). The research field has moved on and this is why criticisms of modern learning sciences are often way off the mark.

Jason Lodge

Most of us who work in this space aren’t hardened positivists like Skinner and are not trying to teacher-proof learning at all. Basic research provides a foundation, principles (such as those derived from Multimedia Learning Theory) that require the professional judgement of a teacher to use effectively in their complex classroom environment with their students. Basic research, therefore, has the potential to empower teachers, not de-professionalise them.

The translation of basic research to education can be effective when not formulaic. Translation from the lab to the classroom and back again is not straightforward but is absolutely possible. The process is best built on partnership. For example, the highly successful Partner Schools Program run by my colleagues at the University of Queensland brings the science of learning and the classroom together through conversations and collaboration between researchers and teachers. Importantly, instructions on how to teach are not being cast out from atop ‘Mount Evidence’.

For initial teacher education to move forward, it would help to empower emerging teachers via a solid grounding in the basic research that has the most potential for impact in the classroom. That research isn’t about how the brain works. The key research primarily comes from psychological science, not neuroscience. What is also important is to lay a foundation for partnership between researchers in the learning sciences and teachers so that we might strive for a convergence of ideas and approaches between the laboratory and the classroom. Focusing heavily on the brain and neuromyths isn’t going to get us there, as useful as they might be for debunking silly Hollywood tropes and supposed ‘brain-based’ learning tools.

Jason Lodge is an associate professor of educational psychology, head of the Learning, Instruction and Technology Lab in the School of Education and deputy associate dean (academic) in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at The University of Queensland. His research focuses on the cognitive, metacognitive, and emotional mechanisms of learning in education. His work with the lab primarily emphasises self-regulated learning with technology.