Hello and happy new year. We start 2023 with a first for the blog: Nina Burridge and John Buchanan in conversation on Teachers as Changemakers in an Age of Uncertainty from the book Empowering Teachers and Democratising Schooling.

Nina: What is a good education in the current context? What are your thoughts on this?

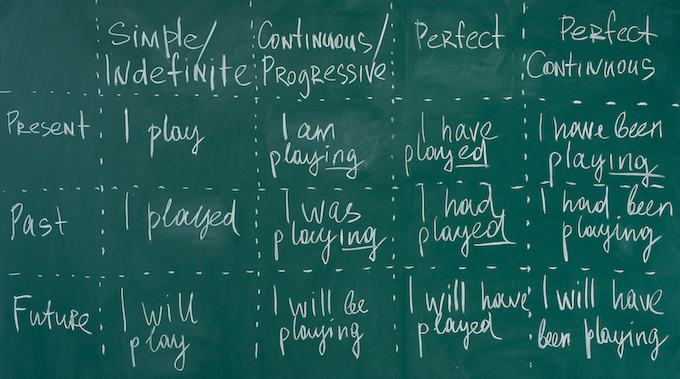

John: I’d say, a good education is defined by what it produces. The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Australia Declaration refers to confident and creative individuals. Members of the community of a community. That’s a slightly watered down version of the earlier Melbourne Declaration, referring to citizens rather than members of community. And the previous declaration referred to ‘equity and excellence’, whereas this one discusses ‘excellence and equity’. So I think that’s an interesting reordering of priorities, but Even so, these are noble aims, and then we subject kids to repetitive basic skills testing, which doesn’t seem to me to be a route towards confident, creative individuals, creative thinkers, etc.

Nina: Yes that is one of the key problems of international testing mechanisms like PISA. And of course we have moved towards this marketization of education. As governments are more interested in statistics rather than creativity. This is where our problem lies and why we need teachers, as change makers.

John: I think that is part of the problem of reducing education to a commodity. And putting it on the marketplace shelf in trying to compete with other jurisdictions. And the thing is, I’m not convinced at all of that: that high rankings and those things constitute a good education. In any case, it’s failing in its own terms, I think, because we’re slipping down the ranks. So I think what’s needed is a fairly fundamental reordering of the education system – matching our practices to those lofty goals; just as we ask teachers to do – devising learning activities that are consistent with educational outcomes.

Nina: Yes, so from my perspective, I think education within Australia and NSW has some particular specific problems at the moment and it is incredibly critical that we focus on the nature of these problems. Some of it is related to the marketization of education, which has indeed created a system which perhaps lacks equity, and it also, as you say it lacks excellence as well. And on this issue of equity I wanted to note that I’ve been doing some supervision of student teachers in schools and I’ve been travelling from the eastern suburbs of Sydney visiting some wealthy private schools to the Central Coast. To be honest I am staggered by the resources disparity between these schools that I saw in one week – it just brought home to me the problems of Equity within the Australian schooling system. According to various indexes, Australia is one of the richest countries in the world. We are supposed to have an excellent education system. And yet, there’s such a level of inequality between the resourcing of government and non government particularly in the less affluent areas – that is shocking. And that brings home to me the clear problem that we have in our education system in this country. Therefore the federal government has to really engage in looking at the role of teachers within our system, but it must also address the funding issues in relation to school resources but also of teachers salaries. Therefore there are some clear big issues for teachers in the 21st century and for the education system.

John: It seems to me the government has decided they will put all of their eggs into the upper echelons basket of the students. That, by whatever means they’ve decided, seems to be the best investment and that sort of commodification concerns me. On a related matter, one of the criticisms of Australian education outcomes is that we seem to have a ‘long tail’ – a long lag in terms of lower quality outcomes among students, so I’m thinking even if it’s not as a means to an end to me trying to fix that inequality. If you’re going to say you want that equity, then surely it’s reasonable to say we’re going to put most of our resources into the communities and the schools that have the least at the moment, to try and even things up. While that’s perhaps a discussion for another time, it certainly doesn’t seem to me that investing most of the money in the already well-to-do communities is going to fix equity – and probably not excellence either, because you want people to aspire. If you can get people from lower income lower socioeconomic communities to aspire. To you know, higher education achievements, I think that’s a good thing. That said, I sometimes wonder if we think university is the cure for everything. I want good car mechanics just as much as I want good teachers, doctors, engineers, etc. I sometimes think the most important professional in my life is my car mechanic, because if he – it’s a he – Is either corrupt or slack or cuts corners, that can have immediate effects for me and for my loved ones. What I want, though, is options and opportunities for all young people.

Nina: Yes, education is not just about university training. It’s much broader than that, education is also related to the idea of the sort of citizens we want to create. I guess what I’m saying is, the role of teachers is to really focus on the sort of society we want to create. Developing good citizens as such that have a compassionate mind that looks at issues that are not necessarily related to financial gain but the well-being of the Community. So developing a teaching philosophy for the 21st century might be interesting to discuss and it would be interesting to have your thoughts on that? Because teaching has become incredibly complex and there’s such demands on teachers and we know that they’re leaving the profession within five years. We’re losing between 30 and almost 50% of the profession that we’ve spent years training. They say, “no, this is too hard. I’m getting out of here and doing something else”. How do we change that and what is a good philosophy on which to base our teaching for the 21st century?

John: This is maybe a strategy rather than philosophy, but I’m thinking further about what you were saying before about producing empathic students who can understand what it’s like to be somebody other than themselves. I guess, too, I want students to be big thinkers. I think most fundamentally, I want them to be big thinkers and problem solvers, and that’s where I think that compassion and empathy comes in. Because I think otherwise, you run the risk of educating a generation of just more literate, numerate ICT-savvy monsters – and that’s a really frightening scenario, I think. Surely we need the best teachers to do that. And so you need to make the teaching profession attractive and it seems to be anything but attractive at the moment. As you say, so many teachers are leaving within five years, presumably feeling disillusioned, and maybe it’s partly too because there’s no longer this idea that our grandparents had a career for life, a job for life. But if that’s the case, if that’s the norm, and teaching has to be even more competitive, I think because it needs to attract people from other professions. And that’s probably not a bad thing itself. I think attracting people with work experience and life experience, I think is a good thing. Good new blood – even though it does worry me a bit that you spend perhaps four years producing a teacher who will only be in the job for four or five years, that seems fairly expensive to me. So for me, one of the questions is how do we make teaching more attractive to attract the best teachers? And also I guess. If you do have the best teachers, that will raise the esteem of teaching. I think in the same way that we think of doctors at the moment. Generally, as soon as you know that somebody is a medical practitioner, you presume well they must be reasonably bright.

Nina: I think one of the problems is that we don’t value teaching as much as we might value some other professions. And yet, as I say, to teacher education students our profession is one of the most important professions around because you are face to face with the kids of the future with the people of the future. These young people, whether they are primary school or secondary school teachers, are actually going to be an influence on young people and perhaps reshape society in the future. So for me, I think this idea of teachers as changemakers and as activist professionals is valid and necessary and as Paulo Friere (1968, 1994) notes Education can be emancipatory. It can change lives. Teaching is not just a job – perhaps it is a moral practice as has been written up in academic research (Pring 2001) so teachers as changemakers will focus on promoting social justice issues, human rights, enabling the skills of critical thinking and initiating the idea of global citizenship. Students should think about how to make a better future a better world for their generation.

John: I think at the moment we’re paying a lot of lip service to teachers. I think governments have come to realise this because of the current teacher shortage. Also, what’s almost universally seen, I think, is the great job teachers did during COVID to keep the system running. But words are cheap, and so we’re not doing anything much to support them. A bit like nursing, you know, another really important job. Other than saying nice things to them, we’re not doing anything practical, or listening to them either in terms of what they want. Also, for a lot of politicians, the system has worked well for them. I don’t want to be too stereotypical here, but I think a lot of them are perhaps from the majority, even though that’s changing ever so slightly. And the system works for them, so why would they want it to change? You know, it’s easy for them to pay lip service. Yes, we must support our teachers better and not just go on as business as usual. The trouble is it’s reached the point where it’s not even doing that anymore. We’re not able to staff our schools, and I think if that’s the case, that’s a fundamental dereliction of duty.

So, we really have to re-evaluate our work with teachers and teachers’ roles and providing them with resources, obviously, but also perhaps a better balance between the pressure that we put on them in terms of compliance and supporting them in their teaching and giving them confidence to actually really be more innovative in what they do in the classroom.

The administration work related to compliance is necessary but more support is needed to allow teachers to maintain their focus on the classroom. Administrative work wears them down. It puts more burden on them, so it just makes them tired so that perhaps makes them more likely to become minimalist. It demoralises them and it just stops them from having the bandwidth, the mental cognitive bandwidth to be big, creative thinkers. So, while we have these lofty aims in some of our vision statements, our curricula are sometimes fairly bound up in, you know, lower-level outcomes in lots of testing, including basic skills testing in competitive exams and in league tables, both within systems and across nations, so everything seems almost destined to take the higher order thinking, and the joy out of teaching. It seems to me that if you want confident creative learners, you start by engendering confident, creative teachers.

Nina: That’s interesting because it brings us to this idea of Martha Nussbaum’s philosophy of Education For Human Development. It focuses on some of these critical issues noted above and understanding the complexity of the world, the differences that exist in societies and having the narrative imagination as Nussbaum says, to apply real world problem solving techniques to seek solutions. So if you look at the challenges of the 21st century today, such as the military conflict in the Ukraine; what’s happening in terms of our own democratic systems, we are seeing a move in the world turning towards more conservative ideas. We also have a climate crisis and we have growing inequality in the world. So these are key issues that teachers need to address with their students. So I think there’s a lot for teachers to do, but at the same time we have to resource them properly to be able to do it.

John: These young people, our current students, are going to have to fix a lot of the problems that are of our making, and that’s going to involve a lot of complex thinking; a lot of selfless thinking. And yet we don’t want them to be too revolutionary in doing that. We still like the good things that our privileges brought us, and in a sense it’s like telling these young people to fix the house. Well, we know that the foundations are dodgy. Unless there’s a bit of an overturning of the status quo, the changes are just going to be cosmetic, and I don’t think they’re going to be enough to fix some of those problems.

Nina: I was also thinking that technology and social media are making the teaching profession so much more complex. Social media has such an impact on students emotional well being and in their cognition. We see again the increasing complexity this is causing teachers. I was recently in a class watching a student teacher teach some year 10 students. I was stunned to see how many of them were playing games on their computers. I would have much preferred if the teacher had told those students to put away their laptops and just engaged in the classroom discussion.

John: I know I’m a bit reactionary in this way, but I think social media, and even the digital world in general has done as much harm as it’s done good to education. It’s got potential to be wonderful to find out things. But I’m not sure if the explosion in knowledge has resulted in an explosion of wisdom. And if anything, I think in some ways I think it’s led to an explosion in contempt for knowledge, because, well, ‘I can find it on YouTube. I Don’t need you as a teacher’.

And I’m not looking for ways to bag social media here, but it seems pretty well-founded that levels of depression and anxiety and powerlessness that social media have increased amongst young people. That seems the exact opposite of what you would hope it would do. You would hope it would empower them to say ‘I can have a voice here’, but it seems to be having totally the opposite effect.

John: I might just mention one more thing in terms of my recent work at various universities in teaching. I think there is increasing pressure to pass students. And I think that’s in part because of reputation protection from the university concerned, and also because of the desperate shortage of teachers. I don’t see how how you can have this idea of raising standards among teaching while you’re just desperate to find anyone who will teach.

In terms of improving teachers’ working conditions, I would recommend less workload through perhaps smaller classes or perhaps less face-to-face teaching – but in the current situation this would not be possible. Improvement in pay and conditions would help but of course governments are reluctant to enable this because of the costs involved. It seems we are in a no win situation here.

A couple of other things in terms of teacher preparation, the move at the moment towards a more apprenticeship model I don’t think positions us well to improve the quality of teaching. Because I don’t think that watching and copying equates to teaching, and I think that’s the default. Even on professional experience, our students tend to watch and copy rather than try and work out, well, why did she or he do it this way. And how and why might I do it similarly or differently? And I think the move to online learning, particularly in universities, is unhelpful. I think the horses bolted. I don’t know if we can go back to being more in the room, but I really like the idea of people being in a room together to kick around a big idea and you know, discuss with each other because, similarly, if you’re online, I think the temptations to be off task are even greater. If you’re in a learning situation, encountering something new and challenging, you need to be devoting everything you can to that. The more distractions there are, the more difficult it is for you to get the most out of this really expensive, really valuable ‘commodity’ is a word that comes to mind, this phenomenon called teaching and learning. I think we need to try and free ourselves from distractions.

Nina: So now just to finish up in terms of examples that you’ve come across where teachers can represent or be seen as agents of change. What examples would you put forward?

I think that there are some important issues that we must address as a society in relation to the role of teachers. I still absolutely value the work that we do as teachers, despite the fact that there’s such as you say, a teacher shortage. We must not undervalue the work of teachers as changemakers in dealing with some of the challenges of the 21st century, such as the climate crisis. So to me this is one example where teachers can be changemakers. I was in New York in November 2019 when the students were engaged in the climate strike. I’ve seen it in Australia as well and I think that as teachers, we should embrace and support and encourage young people to take action. These young people are being absolutely active in their own future and really playing a part in the democratic process. Another example is my work that I do with refugees in Indonesia. It shows me again how vital the work of teachers is. These poor refugees who have fled their homeland, reached Indonesia and their resettlement process is taking years and years particularly to Australia, because it has closed its borders. Hence their children are not being educated – and now the families are having to set up volunteer schools to educate their own children because education is so vital for them. These students in these small underresourced schools are so enthusiastic for learning – quite different to what I’ve seen in some of the classrooms in Australia. This is because they understand the necessity of the process of learning and for them it’s vital. I also see these young teachers who we are helping by providing some basic elements of teacher training trying their best to engage these students in learning. They may not end up being teachers in the long run, but they’ve taken up the challenge, to teach in English because education is so vital in these circumstances. In working in refugee communities you also realise the importance of a focus on human rights and justice in the world.

John: We must not forget that we often talk about rights and freedoms. For me, I think it’s what I call responsible autonomy. Our freedom always exists in context; it’s always limited. Even though I love the idea of freedom, and I love the freedoms I have and would hate to give them up, I still have responsibility. And returning to my comment before about the measure of education is the kind (pun intended) of person it produces, I suppose my question to kids would be, ‘what kind of grown up do you want to be?’ And my question to teachers, parents, governments, and the rest of us would be what kind of grown-ups do you want to produce?

Nina: Totally agree that with rights come responsibilities and that is of course again the role of teachers as changemakers. They must instill in students the importance of speaking up to challenge injustices in the world but with this also comes the responsibilities of being a good active citizen.