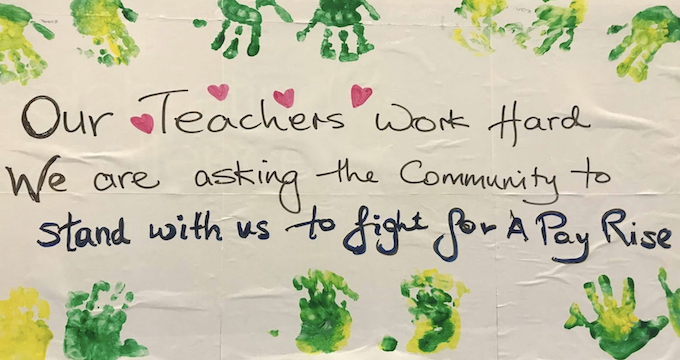

Teachers are striking. Not just in NSW, Australia, where the NSW Teachers’ Federation went on strike when it took to the streets in late 2021. Teachers in the states of Washington, Ohio and Seattle in the United States also took strike action this year in response to similar pressures that Australian teachers are facing. They are demanding smaller class sizes, more specialist support for teachers, higher wages, and better conditions to prevent teacher burnout.

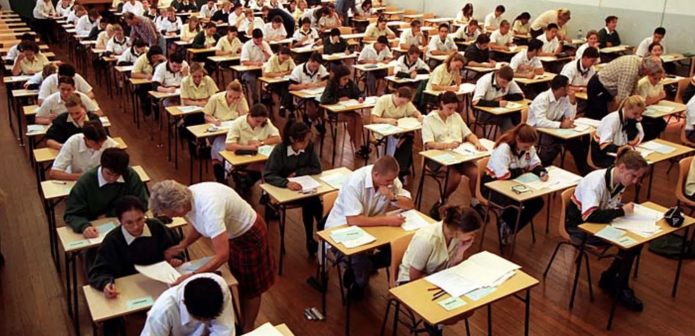

My research has focused on school education mainly in NSW where market-driven agendas have entrenched competitiveness in education systems, contributed to the rise of precarious work in the teaching profession, slowed the growth of teacher salaries, and increased the workload and administrative burden on teachers and school leaders. For the last 40 years, neoliberal policy agendas in education have threatened to undermine the democratic foundations of public schooling and weaken education unions that represent the voice of thousands of teachers.

Research on teacher unions is lacking

Although public education is an issue at the forefront of society, what is lacking in the conversation about neoliberal education reform agendas is how teacher unions attempt to challenge such agendas. Teacher unions are important civic and economic associations that articulate teachers’ collective and professional voice.

As an interdisciplinary researcher spanning the fields of industrial relations and education, my research focuses on the interrelations between employees and employers and their representatives, and the state. For nearly 10 years, I’ve examined the complex contexts in which teacher unions organise and campaign in an effort to understand the strategies they use to resist neoliberal agendas.

My chapter, recently published in Empowering Teachers and Democratising Schooling: Perspectives from Australia, contributes to understanding how teacher unions build grassroots activism and shape campaign strategies to resist neoliberalism and inspire action towards a more democratic future. The chapter is nested in a broader conversation in the book, alongside contributions from teachers and researchers, which is focused on giving primacy to teachers’ voices in education scholarship and public debates. The chapter draws upon insights from my doctoral thesis which examined how one teacher union in Australia has campaigned over the last 40 years in response to various education reforms and threats to teachers’ working conditions.

Lessons in building union power

There are contemporary reports of a teacher shortage crisis in New South Wales. Compounding this is an ageing teaching workforce. While the education and training industry has the highest proportion of employees who are trade union members, revitalising how unions recruit and engage the next generation of activists is a key concern of unions today, not only for teacher unions. According to the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics union membership data from August 2020, only 5% of employees aged 15-19 years are trade union members; this is only marginally higher at 6% for those aged 20-24.

In addition to the profile of unionism changing, the social, political, economic and cultural environment of organising is also evolving. One Former Assistant General Secretary of the teachers’ union I spoke to in my research reflected on this: “[when] you started teaching, you joined the superannuation scheme, you joined the health fund, and you joined the union, and you were just active in the union”.

Renewing strategies to engage an incoming generation of teachers into the profession has been an important task for teacher unions. Strategies have included organising beginning teacher conferences for teachers new to the profession, establishing networks to connect young activist teachers, and offering training and professional development opportunities for members.

Campaigning to advance alternative ideas in public education

The concepts of governance, accountability, efficiency and competition are also changing the way we think about public institutions and public services. Freedom within education is being constrained and democracy is being threatened by neoliberal logics. Such ideology has challenged the fundamental values on which public education systems have been built.

Research shows that teacher unions have responded to this in various ways, including ‘organising around ideas’, connecting with community and campaigning for social justice. This means presenting alternatives to dominant (neoliberal) ideas and campaigning for a vision of quality public education based on the values and principles of democracy and social justice.

Framing campaign messages in response to different contexts enables unions to set the agenda for public education and articulate the voice of the profession.

For instance, using ‘local stories’ can be a powerful way to appeal to parents and community members during campaigns. In one education funding campaign I researched, a Union Organiser from a teacher union spoke about how their campaign was framed around:

“not talking about the billions of dollars and talking about macro level, but just saying to the community this is what it means to you, this is what it means to Billy in kindy when he arrives at the school and he can’t speak a word of English, he’s able to get access to support . . . Those stories can’t be refuted and they can’t be talked down . . . [i]f you’re actually talking about a real human from a real place in a real situation.”

Empowering teachers has also been important in the face of threats to their core industrial and professional conditions of work, as well as the strong criticism and blame that has been placed on teachers over many recent years.

Teachers and their unions are working in challenging times. Continuing to foster a sense of empowerment in teachers and placing the voice of teachers at the centre of education debates is crucial in order to protect and advance the conditions of one of the largest occupations in the world.

Mihajla Gavin is a lecturer in the Business School at the University of Technology Sydney, and has worked as a senior officer in the public sector in Australia across various workplace relations advisory, policy and project roles. Mihajla’s research is concerned with analysing the response of teacher unions to neoliberal education reform that has affected teachers’ conditions of work. Mihajla is on Twitter @Mihajla_Gavin