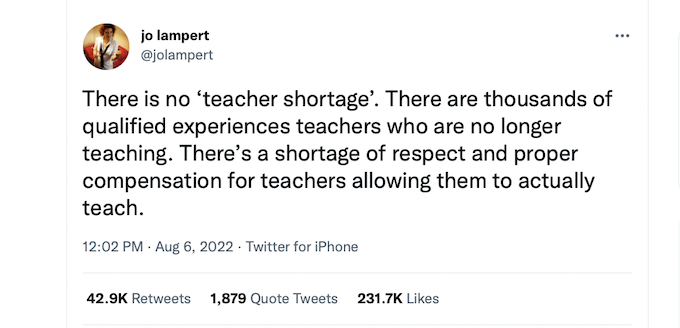

Our dwindling teacher workforce makes headlines every week and new Education Minister Jason Clare calls it “a massive challenge”. A wide range of strategies have been proposed: increasing the respect and reputation of teaching as a job, raising completion rates in university teaching programs, attracting more mid-career professionals into the teaching, offering bursaries, paid internships and reducing university fees for students studying teaching. There are also conversations about keeping teachers in the classroom by making the pay more competitive.

Another option on the table is to fast-track visas for teachers from overseas. But can recruiting teachers internationally work?

Australia hasn’t previously welcomed teachers with overseas qualifications, especially those from language backgrounds other than English. The English Language proficiency scores required by AITSL are higher than is required for migrant doctors (and any other profession we could find). Likewise, the English proficiency scores to enter an Initial Teacher Education program are higher than for any other degree, including HDR programs. This creates expensive additional barriers for non-native English speakers, and could be considered discriminatory, given that native English speakers aren’t required to demonstrate the same level of proficiency.

These barriers are impacting the level of diversity of the teaching profession. Less than one-fifth of of teachers (17 per cent) identify as being born overseas, compared with 33.6% of the wider working-aged Australian population. Further, it reinforces a deficit view of teachers from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, overlooking the contribution that such teachers might make to school communities.

Teachers in countries such as China are highly respected. In Japan and South Korea teachers are well paid and valued as highly educated professionals. Australian ITE programs go through rigorous accreditation to ensure that new teachers have the knowledge and skills they need to be effective teachers, as do other countries. Some countries require all teachers to hold Masters degrees, some require teachers to be bilingual or multilingual. Overseas teachers may actually be more qualified, not less.

A diverse teaching workforce allows culturally and linguistically diverse students and their families to see themselves reflected in their education system. Students will find role models that reflect their life experience, allowing them to feel more comfortable and more able to flourish in learning environments where their home culture is valued. Teachers from racial minorities can understand the experience of racism, and help prevent it from happening, as well as offer empathy to students experiencing prejudice. Studies from the USA have found that teachers of colour are more likely to have higher expectations of students of colour. Studies also found less absences and less disciplinary issues when students of colour were taught by teachers of colour. Most importantly, racially diverse teachers can play a key role in challenging stereotypes about racial minorities among the wider community. In short, everybody benefits from a diversified teacher workforce.

However, our current highly homogenised workforce doesn’t allow for these benefits to be realised. While the few teachers that we have from minoritised and racialised backgrounds bring much needed diversity to the workforce, they can become victims of racism themselves. They regularly fend off criticism about everything from their accents to their dress, skin colour, religion or beliefs. Their pedagogies and knowledge of curriculum are often subject of criticism, whereas for their white anglo colleagues, nuances in teaching practices are accepted as part of individual difference in the profession.

There’s sadly a lack of information about cultural diversity among teachers. Country of birth is a crude measure of diversity, and AITSL admits that it currently doesn’t have more detailed information.

Examining the experiences of teachers from different cultural groups, especially with regards to their intentions to remain or leave the profession, will become available in the ATWD in future, and will provide insight into our understanding of cultural safety in schools for students and teachers of different cultural groups. (ATWD report, 2021, p. 18)

However, we also need a far greater understanding of the contributions CALD teachers can make to school communities, and the circumstances that contribute to schools being the kinds of places where diverse teachers – and diverse students – can thrive.

Welcoming teachers from overseas can do much more than address our teacher shortage. While there does need to be some briefing and orientation into Australian teachers’ legal responsibilities, our curriculum and expectations of teachers, we can find ourselves enriched by a workforce that is more representative of our multicultural, multilingual population and our globally-oriented curriculum. More than just a solution to the teacher shortage: A diverse teaching workforce would add value to Australian schools.

Dr Rachael Jacobs is a lecturer in Creative Arts Education at Western Sydney University and a former secondary teacher (Dance, Drama and Music) and primary Arts specialist. Her research interests include assessment in the arts, language acquisition through the arts and decolonised approaches to embodied learning.

Dr Rachael Dwyer is a lecturer in curriculum and pedagogy in the School of Education and Tertiary Access, University of the Sunshine Coast. She is also the president of the Australian Society for Music Education (ASME), Queensland Chapter.