Rachael Hedger on early childhood reform: implications for our children, the sector, and the economy.

This week, Victoria and New South Wales jointly announced a universal preschool year for all 4-year-old children, offering 30-hours of fully subsided ‘pre-prep’ or ‘pre-kindergarten’. Victoria plans to implement this change from 2025 whilst NSW will begin from 2030.

This announcement demonstrates a significant investment in families and young children, improving workforce participation for mothers, and therefore providing a substantial boost to the economy.

The news is music to the ears of the Early Childhood sector who have advocated for the importance of early learning for decades. The Thrive by Five Campaign, part of the Minderoo Foundation, have advocated for equal and early access to early learning to politicians and the government for some time now. Whilst parents may have concerns about putting their child into an Early Years setting for 5-days per week, at this stage, the opportunity is optional. As the people who know their child best, parents have agency here as to whether they take up the offer, considering what will work best for them within their own family dynamic.

Whilst it’s great to have Commonwealth and State level government support, this initiative is not without its complexities.

A key consideration in these early stages is whether these States have the infrastructure needed to uphold this promise. As it stands, there will be considerable issues in rural and remote areas, with 44% of regional families and 85% of remote families living in a ‘childcare desert’.

Australia’s disadvantaged children have a lot to gain from regular preschool attendance. AEDC data reveals that children in the poorest areas of Australia are three times more likely to demonstrate developmental vulnerability than children in wealthier areas. Universal access could help reduce this statistic. However, attendance alone is not enough to close the equity gap. These children need high-quality, accessible, play-based opportunities provided by knowledgeable and experienced educators.

Crucial to effective Early Childhood education is a rich, play-based program of teaching and learning. The first five years is when a child’s brain develops the most. These years are vital for setting the foundation for life-long learning and children’s ability to form meaningful relationships. It is through play that children engage and interact with the world around them developing creativity, imagination, problem solving, and social and emotional skills. To facilitate valuable play opportunities for children, they need educators who understand the theories that underpin effective play pedagogies. We need educators who are specially trained to support, guide and care for children successfully.

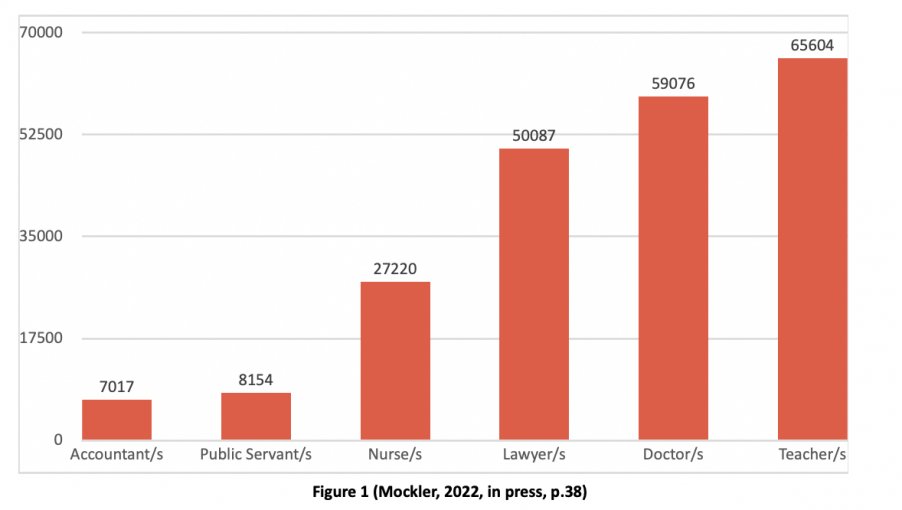

The most significant matter in implementing this reform will be the distinct lack of Early Childhood educators across the sector. Before the announcement on Wednesday, there were an estimated 6000 vacancies for educators in birth-5 settings, with a predicted 39,000 educators needed by 2023. The reform will be directly dependent on a strong Education and Care Workforce Strategy that recruits and retains Early Childhood educators. At present, the lower-than-average pay and conditions results in huge staff turnover as they leave the sector to look for more prosperous opportunities. This greatly impacts children’s learning as they cannot establish and build meaningful, positive relationships with a consistent caregiver.

Working with young children is a rewarding profession. To see children flourish and grow on a daily basis is a beautiful experience. Simultaneously, it is hard work. To care for young children’s needs involves feeding, cleaning and toileting, keeping them safe at all times. To educate young children involves observing, assessing and documenting their learning, preparing resources and the learning environment, and maintaining relationships with families. It involves engaging in play opportunities, extending children’s thinking through questioning and conversation, encouraging new language, and supporting children’s physical, social and emotional development. Few people understand the complexities of balancing the differing demands of this role. Childcare is often seen as only child-care, and this is perhaps why it is underrated and undervalued. An Education and Care Workforce Strategy would need to attract, retain, value and appropriately pay educators for the vital work that they do with young children.

Accompanying the announcement this week, there was mention of incentives to encourage the uptake of Early Childhood Education degrees. Some Eastern universities are looking to offer fast-tracked degrees ranging from 3-years to as little as 18-months. Many will provide up to a year of credit for Certificate III and Diploma qualified applicants, shortening their study time considerably. This approach questions the quality of the Early Childhood educators that we look to produce. If governments invest billions of dollars into the sector only to staff it with employees that have not been adequately educated, we defeat the purpose of what we’ve set out to achieve; quality education for our young children. Teaching is an art form. It takes time and commitment to understand how children learn, the theories that underpin practice, and experience in how to effectively educate Australia’s diverse children. Rushing educators through an Early Childhood education degree will not deliver quality outcomes and would be a disservice to our children.

The reform announcement this week is long overdue and should be celebrated. It is a guaranteed boost for the economy and offers more choice for working parents, but we should tread with caution from here. The biggest and best investment that we can make is in our youngest citizens. They are our future. Australia is beginning to put the economy where it belongs – in our children’s hands.

The main question now is if, or when, will the other States follow?

Rachael Hedger is a Lecturer in Early Childhood Education and Course Coordinator for the Early Childhood Initial Teacher Education degrees at Flinders University. She is undertaking a PhD (Deakin University) in which she explores on how arts-based practices can support children’s science learning. Her research interests focus on how drawing can be used as a vehicle for exploring science concepts, focussing on process and exploration. She is a supporter of learning through play pedagogies and encouraging pre-service teachers to be advocates for young children’s learning.