Throughout this week, we plan to have posts from the conference. Please email jenna@aare.edu.au if you have something you would like to write (quickly) either your own paper or something you have just heard and want to discuss. Thanks!

EduResearch Matters

How strong schools became the backbone of the juggle struggle

When state premiers came out and said that schools were going to close in March of 2020, there was audible panic among parents.

There was one exception to the ‘closed school’ rule, the children of essential workers.

Somewhere buried in those directives was the simple truth about schools – schools are essential for families so that they can keep working, pandemic or no pandemic.

We wanted to know if what we had always assumed was correct, that schools are one of the means that allows women today to juggle more than our mothers.

In short, we wanted to know if schools were an important part of allowing women to work and have children.

While we were undertaking this work during the pandemic, we wanted to understand how working women juggle it all and all the time, not just during COVID.

We spoke with over 200 women to ask how they juggle it all. What we found, for anyone who works in a school, will be unsurprising.

What we found was that schools provide a huge amount of support to working families to give them the chance to pursue their work.

The women we interviewed were from a range of backgrounds. Some had families, some didn’t. Some were partnered, some weren’t, and some were in polyamorous relationships. We interviewed straight women and women within the LGBTIQA+ community.

The women we spoke with reported having a huge mental load to carry. We defined the mental load as the emotional and psychological burden of the little things, the small, everyday, quotidian tasks that keep a house, a family and the world running.

The mental load is everything from, in a family with kids for instance, making sure the children work on their homework, and knowing when it’s due, remembering to pick up milk from the grocery store, checking that the second load of washing goes into the dryer, making sure they have booked in to see the doctor and other various little ‘details and things’ that have to be done around and outside the house.

The biggest issue with the mental load was the job of remembering everything. And, this task fell almost exclusively on the women in heterosexual families.

And the group with the biggest mental load was heterosexual women with children. When it came to the pandemic, those women with children were under the most stress and pressure. As one of our participants stated:

I definitely carry about 90% of the mental load, my husband the other 10%, usually about himself. All other tasks, responsibilities to do with our children, dog and household fall to me. In terms of household tasks, it would be 80% me, 15% my husband, 5% my children. I would love them all to do more but they complain and don’t do it”.

She was hardly alone, we met a lot of women who were in the same boat, who were struggling before the pandemic, but even more during the school closures and lockdowns.

Women we spoke with relied heavily on schools to help them manage their competing demands, indicating that their workload had increased considerably once school attendance was no longer available to their children.

But, while schools definitely gave women the chance to work, it also increased their mental load. Interestingly, it seemed to be the women who were responsible for being the interface between family and school.

In spite of women working more hours than ever before, of our 205 interviewees, we found that 154 said they were the major responsible person in their household. These 154 were tying the children’s shoelaces, turning up to the school when the child was in sick-bay and taking that phone call when the school needed something to do with their child.

We already knew, from the data, that women today are doing more than their mothers ever did. In spite of their increased paid work, they’re spending more time with their children than their mothers did in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, as the following table shows.

We also know men are doing more than they used to, but, in most heterosexual relationships where the family has children, the adult called on to do the school stuff is usually the mother. Some of our respondents stated that even where the father was listed as the primary contact, the mother was the one the school got in touch with.

Interestingly, the women in our study who were in homosexual, or poly relationships with children, reported there was always one person who was largely responsible for the multitasking: remembering the school excursions, the sports kit and the parent-teacher interviews as well as loading the dishwasher, putting on the next whites load and, on top of all that, the stuff for their own paid work. If they were a mixed sex poly realtionshiop that person was, can you guess?, a woman.

But in spite of costing extra work, it was schools, we found, that provide an important opportunity for women to maintain links to the workforce. Schools allowed mums to manage their time and, yes, get a vital break from the kids. However, these women were paying that debt back in time, in the mental load, in remembering what the schools needed of them.

Our book provides a commentary on the lives of women today, presents research, and suggests strategies for balancing the mental load in practical ways.

We found that, before we can have equality within the workplace, there needs to be more equality at home, too.

The Superwoman Myth: Can Contemporary Women Have It All Now? by Jennifer Loh, Raechel Johns and Rebecca English (Routledge) Raechel Johns (left) is a Professor of Marketing at the University of Canberra, and currently the Head of the Canberra Business School. She has broad research interests focus on service management including technology use and also community wellbeing. She also has research interests in management, particularly focusing on workforce trends, the future of work, and productivity. Rebecca English is a senior lecturer in the School of Teacher Education & Leadership in the Faculty of CI, Education & Social Justice at Queensland University of Technology. She teaches into the BCT Curriculum area as well as the sociocultural studies units and was a teacher in both the Catholic Education and Education Queensland sectors for seven years.

How to bridge the teacher and academic divide online

The Problem & the Proposal

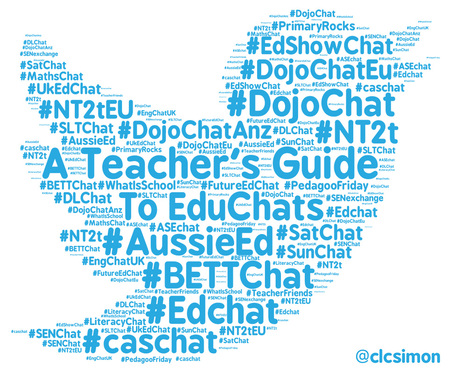

One of the most widely accepted facts in education is that teachers and academics often do not mix. This hurts teachers engagement with research and its application in the classrooms. Social media, and Twitter especially, holds the potential to bring together teachers, academics, and others within shared spaces to develop collaborative approaches to research and to actively engage with it. Important within this is the idea of a pracademic: a person capable of working between and within the teaching profession and the world of research. As such individuals seem to hold the key to narrowing this gap.

Social Media as ‘third space’

The concept of the pracademic is relevant when one considers the increasing expectations for teachers to be both research-based practitioners and data literate. Pracademics have relevance to improving education systems through their boundary-crossing expertise. But how might we better develop and cultivate these pracademics? Social media has an increasingly important role to play in this instance. As a small example, the number of practising teachers attending the Australian Association for Research in Education National Conference is likely low; this is not uncommon for educational conferences. For many teachers, engaging with research is a distant memory, connected more to their teacher training and university days than their current practice. We feel this requires urgent research attention.

Social Media and Teachers: The #AussieED example

There are many examples of social media mediated groups that support the development of pracademic identity. One example is #AussieED, perhaps the longest running education Twitter chat in the world, but certainly within Australia. This Sunday evening chat brings together educational thought leaders, academic study, and all manner of educational ideas in an intense, hour-long discussion open to all. Whilst not all Sunday chats are necessarily engaged with academic ideas or research on this forum, the openness of #AussieEd and its variety means that it serves as a significant and ever-changing professional learning opportunity for teachers, leading them to learn, as well as moving towards research engagement.

#edureading

A contrasting approach is the #edureading group, which was started in 2018, by Steven Kolber. This group brings together educators – howsoever they might be defined – from around the world to discuss an academic article once per month. Participants are asked to read an article before the meeting and then post their reflections in the form of three short 3–5-minute responses on the educational video sharing platform FlipGrid. The group then assembles for an audio-based conversation on the ‘Twitter Spaces’ platform, and this discussion culminates in an hour long ‘Twitter Chat’ informed by the previous two fora’s shared ideas. The learning design of this group allows education-interested people from around the world to bring their own context and experience to the virtual table to speak back to educational research. As a result, we’ve established that this group provides a fertile space for pracademic generation and empowerment.

TeachMeets

TeachMeets, which occur both online and face-to-face, trace their history to 2006 in Edinburgh, where teachers assembled in a pub to deliver short presentations to their peers. This model has continued to develop, drawing on distributed leadership models, it is known as a ‘guerrilla form of professional development’ entirely organised and run by teachers. This model runs counter to the populist and dominant form of professional learning that is increasingly reliant upon the sharing of edu-celebrities and expensive, money-making entrance fees laden with sponsors.

Each of these three examples can carry differing levels of academic rigour depending on their membership, the topic being discussed and their direct engagement with research. But, if you are not familiar with any of these three forms, each is active and continuing and crucially, completely open to all interested participants. This runs counter to the dominant form of professional learning for teachers and academics, which is large-scale, paid lectures and workshops provided by a select group of experts.

Our research

Our research, through an autoethnographic case study approach, showcases the way that Steven Kolber, a practicing teacher, and Keith Heggart an Early Career Researcher used these social media fora to develop our own ‘pracademic’ identities. For each of us, these spaces served as a ‘third space’ that was neither academy nor teaching but allowed for new identities and relationships to research to be developed.

Findings

We proposed five main features of these democratic fora that separates them from less-focussed, less-academic adjacent social media spaces. These features are rigour and depth which requires that members of these groups engage directly with academic research and discuss these ideas in connection to their personal contexts. Whilst personal experiences are crucial, one key feature is discussion beyond immediate cultural context, this means leveraging the nature of ‘context collapse’ in online spaces and the global possibility of educators coming together. This depth, rigour and discussion beyond one’s immediate cultural context is possible because of the free, accessibility of the tools where these groups are formed. Within these fora knowledge creation both individually and as a collective group is of the utmost importance, not simply reading and responding, but building new knowledge through the combined wisdom of these groups. The lowering of boundaries and the shedding of titles and hierarchies within these groups allows genuine and new forms of collaboration to occur. We feel that when each of these five features are present, that these spaces can effectively develop pracademics, unlocking a range of new potentials for educational improvement.

Why does this matter?

This is increasingly important, as recently published research from the Monash Q Project confirms the differing levels of engagement with research, noting especially the differences between teachers and leaders engagement with research within schools. Whilst for education researchers, the engagement with the profession of teaching is also a challenge where the expectations of ‘publish or perish’ and the precarity of many positions provide unique challenges.

Next steps

Though this research is a small-scale, auto ethnographic case study focussed on two educators across the teacher – academic divide, we believe it has real value for new ways of conceiving of professional learning. In addition, we believe the discussion of pracademics and their role for improving education is important and worthy of continued exploration. Whilst the challenge of locating, developing, and collaborating with these pracademics is explored, we believe social media is increasingly important for these processes.

- DOI

https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-11-2020-0090

- Article located on the Journal’s website

Education focused pracademics on twitter: building democratic fora | Emerald Insight

Keith Heggart is an early career researcher with a focus on learning and instructional design, educational technology and civics and citizenship education. He is a former high school teacher, having worked as a school leader in Australia and overseas, in government and non-government sectors.

Steven Kolber is a teacher at a Victorian public school, the founder of #edureading founder, secretary of Teachers Across Borders Australia and a proud member of @AEUvictoria. #aussieED Global Teacher Prize top 50 Finalist

One powerful way to beat the trauma of school transition with joy and fun

On the Monday post lockdown, schools again reverberated with the sounds of all their kids in the playground. In this pandemic much has changed but perhaps none more than schools and the work of teachers. For many parents, teachers and students there will be justifiable anxiety about what students have missed out on. There will be no doubt be a rush in some classrooms to cram missed syllabus content into kids (which will soon be forgotten) as well as re-establish routines. There might be a better way to manage the return to schools by looking at what our neighbours across the ditch have done and are planning when they reopen later this year.

Schools in Aotearoa New Zealand have used the arts and creativity to support students and teachers make a meaningful transition back to classroom learning. An on line resource, called Te Rito Toi was created by the University of Auckland, in partnership with the NZ Principals Federation and the the teachers union that represents over 90% of all Primary teachers. The site provides lesson plans and advice for teachers to use the arts and creativity to help students reflect on their lockdown experiences and consider how they might use those experiences to make their learning more fruitful as they meet their teachers and classmates again.

A central pillar Te Rito Toi is that arts-informed curricular approaches are powerful for individual and community recovery after disaster, strengthening social support and building hope.

For students it is a gentle way back into schools that promotes opportunities for students to create and reflect on how the world has changed during lockdown and at its heart children catch up with relationships before catching up with learning.

For students, it is a gentle way back into schools . . . children catch up with relationships before catching up with learning.

The program is based on decades of international research into what the arts do, that they qualitatively shift the kinds of talk that happen in classrooms and provide students with opportunities to recognise how the pandemic has disrupted their lives and schooling. It also provides creative processes for them to respond to their experiences as they re-join their school communities.

In 2020 the University of Auckland team (who developed the program) carried out a research project with eight schools around Aotearoa about the use of Te Rito Toi in schools. It found that the lockdowns were just another layer of trauma along with multiple traumas happening in the lives of children and their families-the pandemic just exacerbated what was already happening. This was especially true in areas where Covid hit hard and where there are existing traumas such as poverty and dislocation.

When children are busy working hands-on in the arts, teachers observed that it was easier to have meaningful one on one conversations about their worries and concerns. This research demonstrates that the arts provide a space for safe dialogue with the adult teachers about their anxieties such as ‘will my grandad die? What will happen if they do?’ All the big questions best handled outside a whole class discussion. The research found that coming back to school to some joy and fun, along with the excitement of painting, drawing, dancing and moving was critical in supporting student wellbeing. Many teachers in this study, recognising the trauma of transition decided to put aside those more formal kinds of structures to excite kids about being back at school.

In New Zealand Te Rito Toi has been very popular. The lesson plans feature different mediums of expression and provide ways for children to build relationships, explore and describe emotions, engage with possibility, and reimagine the world. The Te Rito Toi team have delivered webinars to over 40,000 teachers around the world that have inspired similar resources in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Hungary. The Te Rito Toi online resources have been used in the US, Canada and Australia. This enthusiastic take up recognises that while routine and syllabus content are critical, they are not enough to support this massive transition and readjustment. The NZ Ministry of Education have joined the Principals Federation, the teacher unions in endorsing the approach for schools in Auckland when they return after months of lockdown.

Te Rito Toi focusses on classroom-based curriculum resource post-crisis. Schools cannot go back to ‘business as usual’ post-disaster and resume normal routines as if nothing has happened. They must address with children the fact that the world has changed and help their students make sense of that change. These resources provide ways for children to reflect and create on their own experiences in a safe way and helps them to make sense of how they might be feeling. As our classrooms spring back to life we might look across the ditch to see how a dose of creativity and the arts can make spaces for our young people to process, reflect and respond to the changing world around them rather than just expecting them (and us) to just get on with it.

The CREATE Centre hosted a Webinar, Coming Back To School Through The Arts, featuring Prof. Peter O’Connor(University of Auckland) and Prof. Julie Dunn (Griffith University) in October, with discussion of some of the resources from Te Rito Toi and how they can be used effectively to support young people returning to school. Professors Peter O’Connor and Julie Dunn highlighted how critical attending to the intrapersonal and interpersonal capacities and needs of children rather than just their ‘academic’ needs. The webinar helped educators understand the background and applications of this arts education resource in and beyond Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Dr Michael Anderson is Professor of Arts and Creativity Education at The University of Sydney and Co-Director of The CREATE Centre.

Professor Peter O’Connor is the Director of the Centre for Arts and Social Transformation at the University of Auckland and an Advisory Board member of the CREATE Centre

The truth about Terra Nullius and why First Nations people say Tudge is wrong to say we need optimism

Australia’s federal Minister for Education, Alan Tudge, will not endorse the draft national curriculum for secondary teachers of Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) because the changes are “overly negative”and could teach kids a hatred of their Country” (ABC 2021).

But from a First Nations perspective, the time has come to speak the truth about what has happened since the invasion of the sovereign lands and waterways, the act of Terra Nullius and the legacy of this mindset.

The draft national curriculum was publicly released for comments in early 2021. It revealed substantial changes to the Year 7-10 History curriculum and is to be finalised and given to all state Education Ministers for their consideration and endorsement by the end of this year.

Since the introduction of the National Curriculum in 2012, many secondary teachers of HASS have lamented the lack of Australian History taught in Years 7-10. Australian History which was previously covered in Year 8 was moved and watered-down into the primary school curriculum, leaving secondary HASS to cover a very broad scope without much Australian and Indigenous History until Year 10.

The new draft History curriculum proposes the inclusion of more Australian focused content earlier; including pre-colonisation First Nation histories in Year 7 and more detailed consideration of Australians’ roles in both WWI and WWII in Years 9 and 10 respectively. Year 10 will still include the civil rights History of Australian and Indigenous peoples – the only Australian and Indigenous focuses to date.

Many of these inclusions will be welcomed and celebrated by Australian HASS teachers, but our purpose here is not to defend the draft curriculum but to question the minister.

Perhaps Minister Tudge is what Noongars call ‘dwokabert’ (deaf ears)?

Minister Tudge argues that contestability should not feature prominently as a historical concept in our curriculum, but that we “must give an optimistic view of our country.” Do these values represent, “the vast majority of Australian people?” Do we not have a responsibility to teach about the pluralist backgrounds and perspectives of our diverse society? Isn’t our role to equip secondary school students with critical thinking skills to make choices, based on well-informed and widely-considered ideas and beliefs? And most importantly, surely Reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples will remain rhetorical unless we teach a true and accurate account of Australian history in order to develop future generations of Australians who are well-informed about Australia’s rich, diverse and unsettled history?

The goals for education in Australia were formally confirmed again in the Alice Springs (Mpartwe) Declaration in 2019. They included the creation of “active and informed citizens.” Minister Tudge’s agenda, to propagate patriotism and blindly optimistic views about Australia, are accompanied by his argument that History “should be about teaching accuracy” rather than contestability. It is ironic that contestability and debate is one of the key pillars of the liberal democracy that the Minister is arguing should be appreciated, while he is, at the same time, rejecting that History should be contested.

This is what is most concerning about Minister Tudge’s rhetoric – he is poisoning the curriculum well by insisting on the unquestioning acceptance of an incorrect, or at least out-dated, version of Australian History. To come out in opposition now to curriculum change, after his government commissioned Marcia Langton A.O. to integrate and thus infuse Indigenous knowledges into curriculum material just last year, is disrespectful and ‘winyarn’ (sorrowful).

Returning to the Howard Era arguments for “accuracy” and teaching “what happened” as fact in History is contrary to the Australian educational goals of developing critical and creative thinkers. If we want a better way forward then we need to look no further than the Australian Coat of Arms with its ‘waitj’ (emu) and ‘yonga’ (kangaroo) standard bearers. Both animals cannot walk backwards and they symbolise forward thinking and national progress.

Australian students should be challenged to understand that there are different perspectives of our National history, it is not a single story. Critical thinkers, in History, ask questions about whose stories are being told, what perspectives are being represented, and whose versions of History are we reading? We do not accept just “his story,” but we look for “her” stories, and “their” stories. It is essential to the process of reconciliation to know the true histories of Australia as it is a vital element in providing systemic change in the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples which holds the power to Heal Country on both sides of history.

From left to right:

Dr Olivia Johnston is a qualified HASS secondary teacher and now an Edith Cowan University lecturer who is upskilling and mentoring the next generation of HASS teachers in Western Australia.

Dr Libby Jackson-Barrett is a Noongar teacher, scholar and researcher. Her PhD thesis offers an accessible insight into Indigenous Theories of Knowledge and Yarning Circles with 3 cups of Tea patience.

Dr Christine Cunningham is an Educational Leadership academic. She admires her early career co-authors very much and is the Higher Degrees Coordinator at Edith Cowan University’s School of Education.

Many thanks to Peter Broelman who allowed the use of his cartoon which is the main image for this story, as selected by the authors

Why Alan Tudge is now on the history warpath

Australian children will never defend the country if the draft history curriculum is adopted. That’s the takeaway from the Federal Education Minister Allan Tudge’s speech to the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) on Friday.

The minister called for yet another curriculum reform to ensure “a positive, optimistic view of Australian history”.

His reasoning? “Individual students learn to understand the origins of our liberal democracy so that they can defend it, they can protect it, they can understand it, and they can celebrate it”.

The impact of such talk on the education system is cause for concern. Curriculum reform is expensive for the economy and disruptive for the sector. Tudge’s comments are unusual given the Australian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (ACARA) just completed a public deliberation over the History curriculum earlier this year.

This begs the question:

What the hell is the Minister doing?

It’s about the election but there is something more. The use of two political spaces, Sky News and the libertarian think tank Centre for Independent Studies (CIS), rather than the more bipartisan National Press Club, supports the campaigning thesis. My previous research has shown CIS and the Institute for Public Affairs have a specific focus on causing education issues to go viral. When an issue goes viral, it becomes something talked about in more households and more online accounts, whether challenged or accepted. As the lobbyist theory goes, more viral = more likely to have popular influence. Add to this Tudge’s online blocking of multiple historians and teachers of history over the past weeks, as they question his weird focus on optimism, a clearer picture emerges. This commentary is not about policy. It is about the election and getting that little word “optimism” associated with the Coalition.

It’s probably electioneering

There is a federal election on the horizon, and even if the Government is re-elected, there will be a cabinet reshuffle. So why is Tudge making so much noise about History education when he only has five months left in the job? I believe the imminent election is the key to unlocking Friday’s weird flex.

It is tempting to look at the transcripts from Tudge’s comments and dismiss them as far-fetched. But it is more important to draw back the lens to view a government with an election in five months, after a pandemic year filled with bad press.

When taking a broad view of the Federal government, it is interesting to note that the word “optimism” is popping up in many Federal press releases and media interviews. Minister for Health and Aged Care, Greg Hunt, has been using the word consistently since COVID19 vaccines were developed, but the word has also crept into other portfolios. Prime Minister Scott Morrison is the “man for optimistic narratives”, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg is optimistic of an economic recovery, Trade and Tourism Minister Dan Tehan is optimistic about resolving the French submarine diplomatic disaster, “government sources” from Attorney General Michaelia Cash’s office say they are cautiously optimistic about resolving the industrial relations bill, and Foreign Minister Marise Payne even has “optimism” in her Twitter profile, even if it is about breeding racehorses.

Optimism has popped up enough times to warrant attention. The word taps into a public desire for something good to happen after the heartbreak and restrictions of the COVID 19 pandemic. We also know that the current federal government is very keen to ensure popular optics. “Optimism” is a useful word for dismissing the Opposition’s criticism of the Government at the same time giving hope to the population. It’s a powerful word that escapes a lot of generalised attention, and does a lot of political heavy lifting.

How “optimism” works in History education

The tactics of this current government’s History education rhetoric is different to the Howard government. The History Wars have a few skirmishes every time there are announcements about education’s role in the development of the nation. While Ministers and their lobbyists clutch pearls over declining scores in literacy and numeracy, and students are squeezed into STEM for the economy, History has always been about what type of nation Australia’s children should be actively informed about. In the past, this battle for the soul of the nation has at least had some semblance of debate, with academics, historians and politicians getting into the nitty gritty of what it means to raise active and informed citizens. They have engaged with alternative readings of events, even if only to dismiss them.

Tudge’s History War is different.

Tudge’s reasoning is riddled with misinformation and weird predictions but he keeps coming back to this word “optimism”. While he drags out the History Wars’ bread and butter about balancing the positive things Australia has done alongside the violence of the colonial past, his desire to squeeze in the use of “optimism” in other ways looks more forced.

For example, as mentioned previously, the review of the Australian Curriculum was just completed in July. It was not until after the Australian public were invited to make submissions on the proposed changes to school offerings that Tudge began to get quite vocal about changing it. Which leads me to wonder, if he really wanted to make the curriculum more optimistic, why didn’t he begin this campaign before the review ended. A closer look at his reasoning shows that some of the items in the History curriculum he thought were pessimistic have already been removed in the latest draft. So why did he think they were worth talking about?

He uses old news to argue that if the draft curriculum goes forward, students “won’t necessarily defend our democracy as previous generations have done” using data from the Lowry Institute to support his claim. Apart from being completely impossible to make that prediction, what Tudge doesn’t say is that the Lowry Institute poll on democracy shows young people’s faith in democracy is on the rise, trending up from 31% of the population believing in democracy in 2012, to 60% in 2021. So using Tudge’s logic, the current History curriculum is doing exactly what it is supposed to do.

But by flipping a 60% win to a 40% deficit, Tudge can politik about the need for optimism.

These are tactics, not ANOTHER education reform strategy

This points to education tactically being used to further the Federal Government’s re-election campaign, rather than a strategic move to save the soul of the nation. Tactics are localised responses to circumstances, whereas strategies are more stabilised and long term. So in other words, the federal cabinet ministers are finding issues to associate with the word “optimism” and putting it in front of as many voters as possible. For education, the History Wars have a history of going viral, even before the internet. And if you look at Tudge’s comments on Friday, the History curriculum is nestled in with the other two big viral topics – literacy and numeracy test scores.

Ultimately, education cannot continue to be used by politicians this way. Education researchers and journalists need to work hard on holding these tactics up to the Australian public and pushing back on the use of words like “optimism”. While researching for this article, it became increasingly noticeable that the media has begun to use the word to describe the Government. And it’s not just the Murdoch press. Every time a journalist associates that word with the Federal Government, they are giving them free political advertising.

This is just another electioneering policy announcement where Federal politicians have called for a review of the Australian Curriculum: History declaring the hearts and minds of Australia’s youth as under threat. This same rhetoric was used in the 1990s when Henry Reynolds and Keith Windschuttle faced off over the “black armband view of Australian history” in the proposed national curriculum. We need to start asking why this government sees the need to renew the History Wars while still pointing out the misinformation in their rhetoric.

Education researchers need to look hard at their expert subjects and then pan out to see if they are simply being used as a pawn in a wider federal agenda. Education has been in a state of flux for many years now and this requires research that pre-empts, just as much as it reacts. That involves looking wider than the education portfolio. If we look outside of our silos, there’s some clues about where we are going.

Naomi Barnes is a lecturer in Literacy, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology

We struggled to make university more equal. Has that battle for equality worked now?

Australian education policy has really focussed on getting ‘equity groups’ into university and then onto completion with initiatives designed to improve access and participation.

That worked.

Recent data indicate that there has been growth in the university enrolment of these equity groups in the past ten years. Published studies have also found evidence for comparable employment outcomes for university graduates from equity groups shortly after degree completion with favourable employment outcomes sustained at three years after graduation.

But what happens next and why does it matter?

Education drives social mobility and levels the playing field for those with disadvantaged backgrounds.

Our study looked at postgraduate study outcomes in tandem with employment for graduates from equity groups in Australia. We found graduates from equity groups are afforded the same, if not better, opportunities to engage in further study after the completion of their bachelor qualification.

But we also discovered graduates from some equity groups, namely those from low socioeconomic status backgrounds, with a disability, or from non-English speaking backgrounds experience weaker employment outcomes including being in full-time employment and salaries.

Why is postgraduate study an outcome of importance?

The opportunity to engage in postgraduate study is an important outcome in its own right, especially from an equity perspective. University degree attainment is influential on social mobility and associated with higher earnings over a lifetime, with higher earnings found for those with postgraduate qualifications. Globally, bachelor degree attainment has been growing and arguably, postgraduate degree attainment is increasingly needed to gain a competitive edge in the workplace, and to provide greater opportunities for leadership roles. Moving beyond benefits at the individual level, there are also persuasive reasons for encouraging a diverse postgraduate student base. Encouraging diversity in postgraduate education will flow on to diversity in a nation’s leaders, educators of future generations and other important influencers of a country’s future.

Furthermore, finances are one of the greatest barriers to participation in higher education. Direct costs such as tuition fees are substantial, but are dwarfed by the opportunity cost of study – the missed earnings from time spent away from the workforce and in study. These costs are exacerbated for postgraduate degree study. It has been argued that social inequalities extend beyond first degrees into unequal graduate outcomes, including postgraduate degree attainment and occupational class.

Postgraduate study and work outcomes

Our study used data on over 40,000 Australian graduates sourced from the national Graduate Outcomes Survey, linked to data from 19 universities in Australia to examine work and further study for bachelor degree graduates. We considered employment and further postgraduate study outcomes for six equity groups: low socioeconomic status; with a disability; Indigenous; non-English speaking background; from regional and remote locations; and women in non-Traditional areas of study. We found that graduates from low socioeconomic backgrounds, with a disability, and from non-English speaking backgrounds experienced lower rates of employment, particularly those from non-English speaking backgrounds whose prospects of being employed after degree completion lagged far behind those from English speaking backgrounds. Conversely, graduates from regional and remote areas had superior prospects of being employed.

Further study opportunity, however, were positive for all equity groups, except those from regional and remote areas. We found, however, that equity group graduates tended to be engaged in study of another bachelor qualification, and did not have comparatively higher rates of study in a postgraduate qualification. The one notable exception here was for women in STEM fields, who had markedly higher rates of further postgraduate research study.

We also examined the outcome of full-time employment for equity group graduates. Once again, the same groups of graduates from low socioeconomic backgrounds, with a disability, and from non-English speaking backgrounds were found to be less likely to secure full-time employment. Separate analyses of hourly wages showed that these exact same groups also experienced weaker earnings.

What does these all mean?

The comparable or slightly favourable employment outcomes for three of the equity groups (regional or remote areas, Indigenous, women in STEM) are encouraging and suggest that higher education policy for these groups are achieving their intended purposes. However, given the weaker employment and earning outcomes for the other three groups (low socioeconomic status, with disability, non-English speaking background), there is still work to be done. Our study was not able to pinpoint the reasons for the weaker employment outcomes due to the nature of the data, but previous studies have noted the lack of social capital and/or labour market discrimination for these groups, and these might require policy intervention and development.

The finding that equity group graduates are more likely to be engaged in further study after their degree completion is interesting, but there remains some issues of concern. Firstly, a higher proportion of equity group graduates are engaging in further study at the bachelor degree level. This potentially limits any advantage that can be gained from further study and time further spent out of the workforce. Secondly, and related to the first point, it is possible that graduates from equity groups feel that they require further study to gain an edge in the labour market. It also raises questions on whether these graduates felt that their first degree did not adequately prepare them for work, and possibly concerns that they felt further investment in study is required to overcome labour market discrimination or other barriers. These important considerations will hopefully be the subject of future studies and action.

Ian Li is an economist based at the School of Population and Global Health, The University of Western Australia. He is interested in applied fields of health and labour economics, particularly on research on the determinants of well-being, economic evaluation of healthcare, graduate outcomes and higher education policy equity. Ian is a member of the UWA Academic Board, the Equity and Participation Working Group, and director of the Public Health undergraduate major. He is an editorial board member of the Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management and a co-editor of the Australian Journal of Labour Economics.

Have we lost trust in science?

Trust in Science, Society, and the Australian State: A Crisis in the Making?

“The return to school has no room for anti-vax sentiment or vaccine hesitancy,” NSW Education Minister Sarah Mitchell told the Sydney Morning Herald. The questioning and the loss of trust in science has been brought into full force by the Covid-19 pandemic and has entered public discourse and all spheres of private and communal life.

Vaccines have been splashed across headlines in Australia, with rapid uptake amongst the latest added cohort tempered by vocal, policed anti-vaccination protests. This questioning of science and trust in scientists poses a much larger question – How are science, society, and the state interacting? Why do understandings of science continue to be limited to ‘STEM’ disciplines rather than all systemic forms of knowledge? And how do educators and researchers respond to such concerns in a higher education context that has been severely hampered by the epidemic whilst its work becomes more visible, and sometimes more important than ever?

A recent symposium held online by Deakin University’s Centre for Research for Educational Impact (REDI), and the Science and Society Network (SSN) sought to spotlight such questions. ‘Science, Society and the Australian State: A Crisis in the Making?’ ran across three days with four panels and a roundtable. Both vaccine uptake and the climate crisis were common threads across the event. Mitchell’s statement about the incongruence of vaccine hesitancy and open classrooms begs for debate from university leadership and institutional representatives, but crucially requires inter-disciplinary perspectives and a view across philanthropy, private sector, government policy and media.

Scepticism and loss of trust in science was a major thread throughout the symposium. Professor Emerita, Raewyn Connell suggested that the proliferation of knowledge may be attributed to its commodification. However, dealing with this knowledge was the key question – How do we communicate across disciplines and avoid miscommunication in a sea of knowledge? Brian Schmidt, Nobel Laureate and Vice-Chancellor, Australian National University commented on the rise of the internet and how we now face a drowning out the voices of the academics and experts. He asserted that in the educational context students can be taught how to understand this information and learn how to act critically and ethically.

With the proliferation of knowledge claims there is a tendency to deprive science of its context, nuance, and complexity. When this happens the ability to appropriate or simply deny scientific knowledge becomes much easier. The rise of misinformation and conspiracy theories available online and on social media compete with knowledge claims from experts. Alexandra Roginski from Deakin University spoke about her research on ‘Conspirituality’ and how deep social rifts have been created through questioning the seriousness of Covid-19. Roginski provoked us to consider the historical precedence of misrepresenting science and attacking of scientific consensus. These are not new phenomena and have a history within the campaigns of the tobacco lobby. From a public facing perspective, epidemiologist Catherine Bennett from Deakin University discussed her role in communicating epidemiology expertise with the media. She stressed the importance of starting conversations and figuring out what information people have. She clarified that some people unknowingly spread false information while others may do so on purpose. A sympathetic and informed position can enable dialogues which convey enough complexity to explain key ideas and communicate effectively.

As the symposium continued, the role of the educational institution became a key focus. Centring on the curriculum, Mark Rose from Deakin University discussed the impact science and policy on indigenous Australians. He advocated for a curriculum that balances the many facets of modern Australia and equips children to deal with competing worldviews, allowing a nimbleness of mind to see different perspectives, yet remain anchored at the same time. Focusing on the university, Tamson Pietsch (University of Technology Sydney) used a framework of ‘publics’ as she acknowledged that universities are deeply dynamic and political in nature. She placed climate change at the centre of the issues around which publics must come together to bring demands on governments and institutions. Student and broader educational publics can act to meet the challenges facing universities, the educational sector and, to an extent, help shape society at large.

Finally, it became clear that tackling eroding trust in science is not just a job for ‘the scientists’, although it is often presented as such. The latest reform to higher education illustrates how STEM values have been favoured above critical thinking and creativity offered by the humanities. However, as Joy Damousi from Australian Catholic University explained, the collaborative skillsets of both STEM and HASS are required to tackle global challenges. The so called ‘divide’ between the two areas of knowledge is complicated and nuanced. Glenn Withers, Professor of Economics, Australian National University argued that there is value in all forms of knowledge. In particular, he suggested that holistic knowledge offered by indigenous knowledge systems may provide a way forward to work across disciplines and should be developed and institutionalised as an additional learned academy.

With the threats of climate change and Covid-19 playing upon our collective psyche, grappling with the issues of science, society and the Australian state is a critical task. So where do we go from here? The symposium debating the nexus of science, society and state has helped advance a set of critical debates. Tackling vaccine hesitancy and climate change is an interdisciplinary task, which requires educators and researchers to think critically and creatively. Educators, researchers, and institutions play an important role in forming publics and taking a stance. The role of nuanced, yet clear communication is required to spread accurate knowledges against a plethora of information to prevent misunderstandings and gain trust. Finally, taking different knowledges into account, such as indigenous knowledges, may offer us a way forward in facilitating holistic and interdisciplinary work to take on the developing challenges we collectively face.

Natasha Rooney (Deakin University) is a PhD Candidate at the Alfred Deakin Institute of Globalisation and Citizenship, Deakin University. Her research is on the circulation of epigenetic and postgenomic models of life in the Global South.

Playground duty really is quality time: how joyful learning happens outside the classroom

The Quality Time Action Plan is described by the department of education as an approach intended to reduce and simplify administrative processes for teachers and provide them with more time for “high value tasks”. It is here that I have a quibble with this document and its definition of playground duty or supervision at lunch and recess as a “non-teaching activity”. I see this definition as problematic and at odds with the important role teachers play on school playgrounds and the learning that takes place in this setting.

Teaching does not just happen in the classroom

The playground is one of the most important places of learning, it is here that children and young people develop socially, physically and practice a degree of autonomy outside of the classroom. A learning that is as important as that which takes place indoors. The role of the teacher is far more than a provider of knowledge. Relationships are the heart of our work. The playground offers us a space to interact with our students, to observe them in a different light, learn about their interests, strengths and vulnerabilities- an understanding that is essential for building our professional knowledge and informing practice.

Teachers on the playground have a role that goes beyond keeping children physically safe and opening yoghurt. It is here they can offer support to students as they negotiate new or challenging social and physical situations. The playground offers young people a place for autonomy and socialisation. It is here they practice important skills that contribute to their social competence, such as sharing, managing conflict, making friends and learning new skills. Teachers participate in this learning by ensuring students have appropriate equipment to play, such as balls, hoops and skipping ropes. They can make suggestions about how to communicate more effectively, self-regulate, take risks or de-escalate conflicts.

In American schools, playground duty is provided by non-teaching staff, often a parent is paid to fulfil this role. In my experience this resulted in confusion as school rules were implemented inconsistently and according to the assumptions of the adult standing on the yard. I recall one officious parent banning children from trading pokemon cards for no apparent reason other than she did not like the game. Students had no idea when they could run, what they could play or often why they were in trouble. What happened on the playground often stayed on the playground and teachers remained unaware of the social dynamics and the impact they had on the children in the classroom.

Playing is learning

The wording in the action plan denies the important role of teachers in supporting this learning. The playground is a valuable resource for students and teachers as it is the primary place for playing. Play, in its many variations in primary and secondary years, offers much more than a place for children to “let off steam”. Vital social and emotional learning happens when children play and interact on the playground, they develop their awareness of themselves, of others and their capacity for acting with responsibility and kindness. Teachers can model this for children, to facilitate play in the early years, and in the primary and secondary years, encourage social inclusion and give emotional support when needed; this can be as simple as putting on a band-aid to address complex matters such as bullying. The playground is the heart of the school community and a place for students and teachers to play and come together for the wellbeing of all.

Our duty when schools reopen

Studies show that student wellbeing should be the highest priority for schools when they re-open. For many students, learning from home has been a period marked by significant anxiety and social isolation. Reports show what our students missed most about school was playing with their friends and their teachers. Removing teachers from the playground takes away their opportunity to reconnect with their students, to be present with them as they return to school, to share their concerns and more importantly experience the joy of being together again. Surely this should be considered as “a high valued task”.

Olivia Karaolis teaches across the School of Education and Social Work at Sydney University. She completed her research at USYD after working in the United States in the field of Early Childhood Education and Special Education. Her focus has been on creating inclusive communities through the framework of the creative arts.

Main image: CC BY-SA 2.5, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6427507

Not every principal will love the arts but every arts teacher does. They need support

Australians have leapt online to participate in arts events. More than 30% of Australians have engaged with arts events online and more than 40% have participated in some form of art-making in any of the artforms, dance, drama ,music, media art or visual arts.

That shows the Australian appetite for arts of all kinds. But what happens at a school level? The arts is one of the eight learning areas in the Australian Curriculum. While each state and territory has a particular approach to how the curriculum is put into place, schools are best placed to determine how to deliver the arts to their students.

Ultimately the school principal decides the allocation of time and resources for learning areas.

Not every principal is going to love the arts, but every arts teacher does. High-quality arts occurs when students and teachers share the tools of creation and this collaborative approach cultivates the student’s individuality rather than focusing on fulfilling pre-specified outcomes. I undertook case study research of eight NSW Specialist arts teachers. These teachers identified that it was not actually the curriculum but other factors within the school which influenced how the arts were positioned.

The values held by the school are led by the school principal who must fulfil required accountability requirements from NAPLAN to mandated curriculum, in addition to managing the day to day running of the school. The principal may be focused on the outside perception of the school, evident in the number of student enrolments, NAPLAN ranking on the My School website and other external high stakes test results such as the Year 12 school completion rankings. Yet, the principal could be focussed on the internal workings of the school including the students’ learning experiences, teacher autonomy and a sense of community within the school.

Six factors were associated with the principal’s focus which determined the place of arts education within the school: student numbers; curriculum regulation; resources allocation; teacher autonomy; student autonomy and interest and a culture of community. Within these factors I found that the teacher’s anecdotes identified if the principal held an outward focus on the public perception of the school or an inward focus on the student learning experience.

Student enrolments and curriculum regulation

Outward focussed leadership centred upon numbers of students enrolled in the school or within a subject.

One teacher reported that in one year group, French was timetabled for just four students, but although ten students wished to enrol in it, drama was not timetabled as the school had set a minimum quota of twelve students.

Curriculum regulation in NSW also played into this situation as languages are mandated in years 7 and 8 but drama is not. Schools may allocate lower priority to learning areas that are not directly associated with high stakes testing such as NAPLAN and the Higher School Certificate. Independent school teachers in my study noted that their principals considered the My School profile of the school contributed to public perception of the school.

By contrast, two other teachers reported high levels of student participation in the arts supported by their respective principals who were inwardly focussed on the student experience. Creativity was valued in learning at one school where the principal recognised that students who participated in the arts achieved top academic results across learning areas. At the other, a primary school, students were busy with rehearsals for the musical production as well as class activities leaving no time for behavioural issues. Additionally public perception of the school was enhanced through the whole school musical production.

Resources allocation

Timetabling the arts within the school day, provision of physical resources such as paint, instruments, suitable space and allocation of specialist arts teachers contribute to positive arts experiences within the school.

Teacher autonomy

Teachers with strong subject-knowledge and belief in their students’ capacity continue to teach the arts against the odds within their schools. But collaboration and collegiality among teachers across learning areas in a school is more conducive to teacher career satisfaction and job longevity.

Student autonomy and interest

The random allocation of arts curriculum to teachers who are not confident to teach the arts may limit the learning that takes place and potentially make the classroom boring for students. Students need to have control over their learning, and particularly in the arts students will develop their creativity, risk taking and collaborative problem solving. These serve to inspire the students’ interest. But, expectations of outcomes limit the students’ view and force them to measure themselves against pre-specified outcomes. In the arts students learn through making mistakes . Curriculum interpretation that focusses on only on the final outcome, misses the meaningful learning that actually occurs in the process of making the artwork or performance.

A culture of community

Teachers in this study reported a range of arts activities in their schools that created a culture of community. One regional teacher ran a school holiday drama camp which gave more isolated students the opportunity to connect with peers. Teachers reported that through their participation in the arts students felt they were contributing to and were part of a larger community.

The student experience is more than curriculum

The inclusion of the arts in the Australian curriculum legitimises it as a learning area. As teachers in my study have reported, it is factors outside the curriculum that ultimately determine the place of the arts within the school. High stakes testing and the MySchool website do not provide a true three-dimensional picture of the student experience in any school. School principals need to focus on the students’ learning experiences within the school. Additionally, teachers need to buy into curriculum reform to ensure positive action.

And principals should get behind their hard working staff.

Linda Lorenza has a PhD in arts education and curriculum policy and is head of course for CQUniversity’s Bachelor of Theatre degree, lecturing in acting and theatre studies. She is recognised for her education work in the Australian arts industry at Bell Shakespeare, where she was involved in the Theatrespace longitudinal research study into the influences on young people’s attendance at theatre; and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Her recent research includes teachers’ responses to curriculum change in the arts.