The announcement of another review into Initial Teacher Education ( ITE) has sparked a flurry of responses from a range of players, even as many of the profound reforms from the previous Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) in 2014 still being bedded down. While there is evidence to suggest otherwise, a premise that underpins the new review is that initial teacher education programs in Australia are ineffective, and by association, those of us who work in initial teacher education need to lift our game.

Initial teacher education remains a political football.

Some see this new review as an opportunity to build on the success teaching educators have built over the past seven years, unions are concerned that professionalism and standards for teachers may be eroded, others argue that universities have dropped the ball on producing quality teachers. It is still unclear how contributions can be made to the new review, and whose voices will be listened to, and whose will be ignored? And, most importantly, will those who work in initial teacher education be rendered invisible in the debate?

This politicisation of what’s important to the profession has a real risk of side-lining professional educators who know, based on their research and scholarly works, what the problems are.

So, what do teacher educators say about their work?

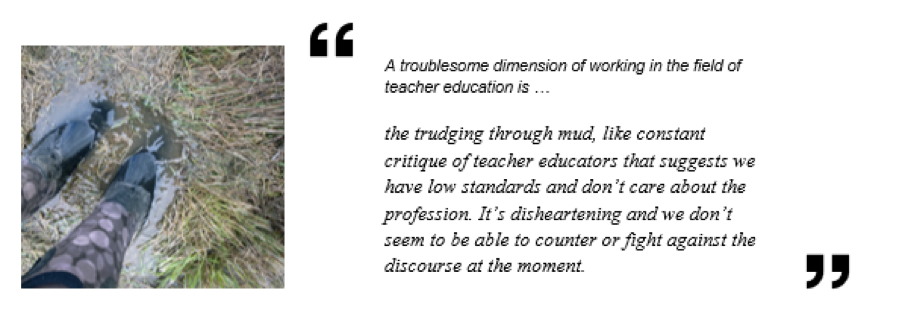

Coincidentally—or perhaps serendipitously—we have been leading a research project since 2020 where we asked those who work in ITE to share their views about various aspects about their profession. As such, we see our work as very timely for this touchstone moment to ensure the stories of those who work at the chalkface of ITE are heard and seen. Through our research teacher educators provided postcard style responses (with a combination of both image and short text). We share here some of the words teacher educators from around the world used to describe the complex nature of their work, along with a few of the images they provided, which also offer powerful visual metaphors about working in ITE.

The privilege of shaping the future of education and teaching

Teacher educators spoke of the delightful aspects of working in teacher education, where there is “the opportunity of working with and learning from so many different people – academics, pre-service teachers, professional staff and feeling like you are part of something really important”.

Several teacher educators relished being involved in shaping the future of education—and by extension—the lives of early career teachers: “It energises me and reminds me of the privilege of being able to shape the future of education in Australia”.

But there are challenges

Despite being part of a profession with potential to change others’ lives, teacher educators identified some troubling aspects of their work. Several referred to the “increasing control” and a perception that we are undermined in the work we do by the “constant critiques of teacher educators that suggests low standards and [we] don’t care about the profession”.

It’s not that regulatory oversight of the profession in itself is the problem, teacher educators said; It’s the decreased control by the profession of the profession that is of great concern: “The constant intervention by bureaucrats and policymakers, most who have never been teachers who impose unhelpful demands on the teaching profession and teacher educators.”

Teacher educators find it troubling that sometimes people outside the profession think we “don’t know what we are doing” and that somehow, “politicians think they know better”. It can be stifling and take teacher education in the wrong direction.”

“The constant government blame and mistrust of teacher educators…and the “countless inquiries that lead nowhere and undermine public respect and confidence”, prompting feelings of teacher education being “such a heavy gig, carrying the weight of expectations of students, universities, communities, employers and governments”. This perceived distrust, and “not quite knowing what policy imperatives are around the corner and dealing with political influences that are not informed by evidence”, is certainly having an impact on some teacher educators.

Working to change and improve the system from the inside

Despite the draining and debilitating effects of never-ending reviews and public critique, our research shows that teacher educators nevertheless remain hopeful: “We continue to find interesting and creative ways to do things and it gives…hope that we might change the system from the inside”. They carry out their work in ways “in which the meaning and purpose of education emerges out of silence and stillness, rather than the sound and fury”.

Away from the sound and fury that can be whipped up, working with pre-service teachers and watching them develop, provides a sense of optimism and hope for many teacher educators: “Despite the challenges administratively and in delivering a crowded curriculums the high level of expertise demonstrated by graduates is quietly fulfilling. Classroom readiness is outdone by passionate and gratifying stories from the field”.

Teacher educators say they are inspired in their work by “the enthusiasm, compassion, courage and energy of many early career teachers [who] have the potential to speak up and not accept the controls that are constantly being placed on the profession. They will need to be strong and tenacious and not accept the blame so often heaped on our profession”.

Where next with the ITE political football game?

In 1997, a group of teacher educators known as the Arizona Group wrote, “The unseen children in our schools ignite our passion for knowledge, our commitment to passion, and our desire to improve future teachers: we feel a moral obligation to the students of our students”. Our research highlights a similar concept at play in the work of teacher educators—they recognise the privileges and the responsibilities they have to the profession, future teachers and to the students of their students, however they must grapple with the shifting and ever-increasing levels of accountability that are imposed.

While in the public realm teacher educators are often ‘invisible’ or easy targets for political point-scoring, the snapshots we have shared here highlight the capacity, commitment, and care of those working in the field of teacher education, and their willingness to advocate for their profession, their students, and students in schools. This may be an opportunity to build on the ‘good work’ in ITE, but it is also high time that the government listened in meaningful and authentic ways to the voices of teacher educators in this latest review of teacher education.

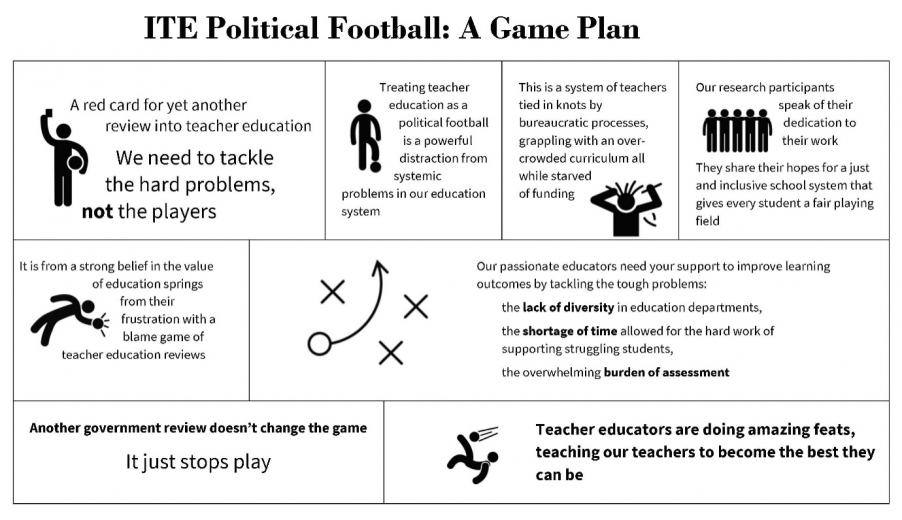

In summing up, our key moves and ideas in this current game of ITE football are outlined in the following game plan.

About the study

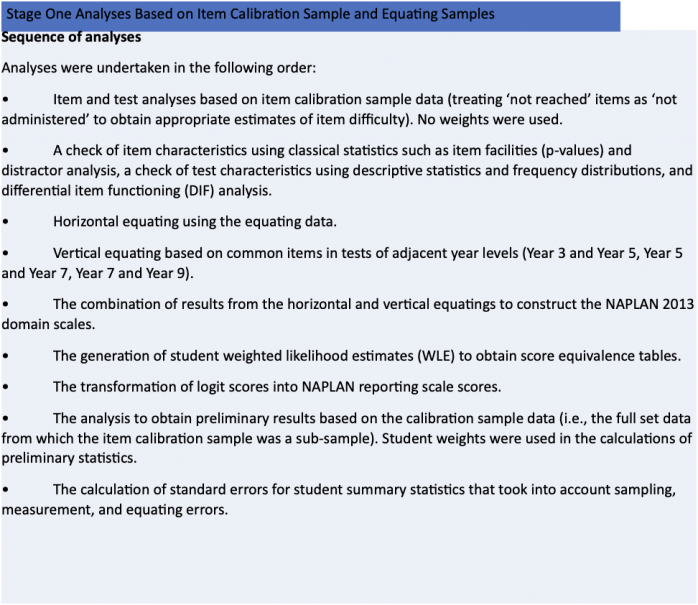

Over 100 participants who work, or have recently worked, in teacher education—predominantly within Australia but also internationally—were involved in the project, which commenced in September 2020. We used an online survey instrument to invite our participants to share postcard style responses (both image and short text in an approach that mirrors earlier research) in response to prompts about the troublesome, delightful, ambiguous, and hopeful aspects of working in the field of teacher education. The juxtaposition of text with images through arts-based research (ABR) genres offers opportunities for new and unanticipated meanings.

AUTHORS

Amanda Belton is a data creative working with education and arts researchers to visualise research information. She works with playful approaches and empathetic design principles to communicate research data visually into the digital realm. Amanda’s work combines an obsession with gifs, a keen interest in animation and mixed reality with interactive information design. Amanda is on Twitter @DataCreative

Robyn Brandenburg is an associate professor and the associate dean, research at Federation University Australia. She researches teacher education and mathematics education and is the immediate past- president of the Australian Teacher Education Association. Robyn is on Twitter @brandenburgr

Ron “Kim” Keamy is an associate professor and teacher education researcher in the Centre for Program Evaluation in the Melbourne Graduate School of Education at The University of Melbourne. His recent research is in the area of educators’ professional learning where he is increasingly using arts-informed research methods, and research into the implementation of a teaching performance assessment—the Assessment for Graduate Teaching (AfGT). Kim is on Twitter @KKeamy

Sharon McDonough PhD is a researcher in teacher education with advanced disciplinary knowledge of sociocultural theories of teacher emotion, resilience and wellbeing. Sharon brings these to explore how best to prepare and support teachers for entry into the profession, how to support the professional learning of teachers and teacher educators across their careers, and how to support wellbeing in education and in community. Sharon is on Twitter @craftyacademic

Mark Selkrig is an associate professor in the Melbourne Graduate School of Education at the University of Melbourne. He works in the fields of teacher education and creativities and the arts. His research and scholarly work focus on the changing nature of educators’ work, their identities, lived experiences and how they navigate the ecologies of their respective learning environments.Mark is on Twitter @markselkrig