This work came to life through the painting of Elder, educator, artist and Honorary Senior Research Fellow, Aunty Denise Proud.

We are at a time where educators are thirsting for information, not just about Indigenous peoples, histories and cultures, but also how to address professional standards of practice in Indigenous education. The Australian Professional Standards (particularly 1.4 and 2.4) require teachers to understand and respect Australian histories and be capable of delivering education to Indigenous students. There are compulsory courses now in teacher education programs, yet, many teachers continue to report that they aren’t confident in practising the many aspects of Indigenous education.

In response, we decided it was important to listen as teachers said they weren’t confident in doing this key part of their professional roles.

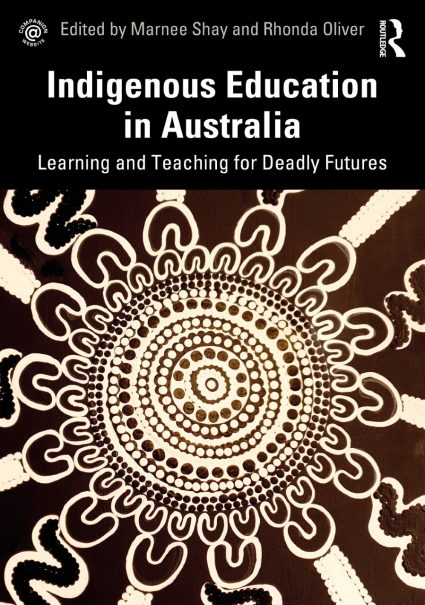

We wanted to create resources to support them in this work, along with the other resources already developed. We felt there was an urgent need to bring together some of Australia’s top educators to develop and deliver a strengths-based book, “Indigenous education in Australia – Learning and Teaching for Deadly Futures”.

We have come together as Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal collaborators for this book because we share a strong desire to see all of the excellent policy reforms that have happened in Indigenous education in Australia come to life. Marnee, who has several research projects in schools around Queensland and has been coordinating Indigenous education coursework for pre-service teachers at the University of Queensland, and Rhonda, who is also regularly in schools in Western Australia for her research and is also the Head of the School of Education at Curtin University, have for too long witnessed the impact of the deficit perceptions that frame Indigenous students and their families.

To us, there are still large inequalities needing to be addressed.

That is why we decided at the beginning of this project that a strengths approach must underpin the framing of the book. That is, our work would start from a position where we emphasise the strengths of Indigenous peoples, their capacities and capabilities. Indigenous peoples are experts in their lives; and if there are problems then the problem is the problem, the person is not the problem. There is a power in stories which reimagine change.

Yes, power in reimagining change but also power in the many opportunities for educators to learn more about the richness and wealth of embedding Indigenous knowledges and perspectives into Australian classrooms. As one of the world’s oldest continuing cultures with 65, 000 years of knowledge and history, if we as educators don’t embed the full histories of this Country, we will effectively rob all Australian students of understanding the Country they call home.

As Indigenous knowledges and perspectives are a national cross curriculum priority, we know educators are eager to ensure they can develop authentic, accurate curriculum. There are chapters in the book that help educators understand how to locate suitable resources and materials and how to work in partnership with local communities in ensuring the curriculum is as localised as possible.

There are many examples across chapters in the book of positive outcomes that have resulted in schools and communities working together to achieve outcomes for their students. There is also a chapter that provides another tool or framework called ‘YARNS’ – this tool aims to support teachers to think critically and with rigour in relation to the types of materials and sources they introduce into their classrooms.

The chapters use literature, research and practical experience to inform discussions about different aspects of Indigenous education. That is, within each chapter there has been an attempt to translate research and theory into practice, focussing in particular on the question: what can teachers can do in their practices to incorporate Indigenous education in their professional practices? There are chapters that speak to the diversity of Indigenous learners, how to support the identities of Indigenous students, how to support students from diverse language backgrounds. As editors, along with the authors of each chapter, emphasis is given to the ideas that: Indigenous students are diverse and unique; that there is no one way of supporting Indigenous learners, and that excellent and innovative teaching practices should serve students positively from all cultural backgrounds.

The story of our book came to life through the painting on the front cover of the book. This was done by Elder, educator, artist and Honorary Senior Research Fellow, Aunty Denise Proud. Aunty Denise tells the story of two knowledge systems coming together, using black and white symbolically to represent Indigenous and non-indigenous people sharing, learning and collaborating for brighter futures of young people. The Aboriginal symbols for people are used, the smaller U shape symbols represent the children/young people and the larger U shape symbols represent the adults who support and nurture them with the rich knowledges of this Country.

The field of Indigenous education has been led by ground-breaking Indigenous education scholars: Professors Nerida Blair, Peter Buckskin, Tracey Bunda, Paul Hughes, Kay Price, Lester Irabinna Rigney, Cheryl Kickett Tucker, Jay Phillips, Lynette Riley, Grace Sarra, Chris Sarra – there are far too many to mention all by name, but we recognise the hard work and tenacity of these scholars who paved the way for the opportunity to create the space where we can continue to support educators to improving their awareness and understanding, and their practices in relation to Indigenous education. We also acknowledge the Elders, parents and community members who have shown incredible persistence and patience in advocating for better outcomes for their children and young people; and of course the many school leaders and teachers who have been doing this work constructively and effectively, sometimes in the face of resistance and complexity.

We have brought together an impressive list of authors for this book who have written about a wide range and diversity of topics. Some are well established voices in the field, and some emerging. We tried to find a balance of voices including practitioners and researchers, but we recognise that there are many more voices and stories yet to be told in this space.

We have also curated a podcast series to accompany the book. The link to the podcast series will be available on the Routledge page and anyone interested will also be able to access the podcasts through their usual podcast app. The podcasts are yarns with authors about their journeys in Indigenous education and where they talk about key topics in their chapters.

The book is by no means a ‘one stop shop’ – but we believe the book will be a useful resource for anyone interested in strengths-based approaches to Indigenous education. This book may also be of interest to people working in policy settings as many of the ideas put forward in the book are evidence-based and speak to the current Indigenous education policy setting. We hope the book makes a positive contribution to the already excellent array of resources available to educators in Indigenous education.

“Indigenous education in Australia – Learning and Teaching for Deadly Futures”: a new strengths-based text book for pre and in-service teachers on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education (Routledge)

Marnee Shay is an Aboriginal educator and researcher and a senior lecturer in the School of Education at the University of Queensland

Rhonda Oliver is professor and head of the School of Education, Curtin University, Australia.