The pieces in this collection are our reflections on the ongoing inequities in education that have been amplified or illuminated by the COVID-19 global crisis. We hope our reflections help readers consider how education work might respond to and address these inequities.

All of these pieces were written during early May 2020—prior to the death of George Floyd and the global movement that ensued. Though the reflections in the collection predate George Floyd’s killing, many of the issues raised in this collection are part of the same unequal system that produces Blak/Black death, through the virus and beyond.

We are all staff or higher degree research students from the Social Transformations and Education Research Group at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education.

Our pieces meditate on the ways the teacher has been positioned through the crisis and what this says about how our society sees teachers (Amy McKernan); the many roles played by schools in the pursuit of mass schooling (Nicky Dulfer); the politics of expertise (Jessica Gerrard); schools futures and Indigenous history (Ligia (Licho) López López); possibilities for investing in community as key to education (Sophie Rudolph); opportunities for rethinking the local in relation to global problems (Rhonda Di Biase and Bonita Cabiles); and the importance of attempting to understand each student’s emotional life and journey in supporting learning communities (Michelle Cafini).

Our Pivoting Teachers By Amy McKernan

So what does “mass schooling” mean to us now? By Nicky Dulfer

Saving education: Trust me I’m an expert By Jessica Gerrard

Ancestral 2020 vision: Chronicle of a death foretold By Ligia (Licho) López López

Here’s our chance to refocus on education for community, not just for the economy By Sophie Rudolph

Turning global adversity into advantage: Working towards education for all By Rhonda Di Biase and Bonita Cabiles

Which boat were you in? by Michelle Cafini

Our pivoting teachers

By Amy McKernan

In my job I teach teachers. Some of my students are working to qualify as teachers, some are teachers already established in the profession. This semester, I have been deeply concerned for my students who also teach. They worked through the term one holidays to accommodate two possible futures – a return to school as we knew it and an about-face to distance learning.

They ‘pivoted’, and now they must ‘pivot’ again. They sit in my webinars with grey faces, tired and quiet, somehow still submitting assignments amongst all of this. Somehow, they are still determined to become more knowledgeable, more skilled, and better teachers.

My teacher students have worked even longer hours than before, implementing a whole new way of teaching, and redeveloping months and years of planning for a completely different world. They have drawn on considerable reserves of expertise and ingenuity to keep their school students learning, all the while closely monitoring wellbeing, and performing the emotional labour of caring.

I have watched over the weeks as the teachers in my classes have become withdrawn, resigned to the fact that they were the last to be considered in this global pandemic, that the decision to close schools appeared to be based not on the possible threat to teachers’ wellbeing, but on the economic wellbeing of families who must work and the safety of grandparents who might need to babysit.

I’m not suggesting that the needs of families should not be a factor in decision-making, of course they should. But the silence on teachers’ safety, including the safety of the many immunocompromised teachers, has been deafening. No one seems to acknowledge the likely mental and physical health issues teachers face as they managed the increased workload of teaching students both in and out of the classroom.

There has been an implicit assumption that teachers will take up a significant burden in this crisis. As is so often the case, teachers have little agency and little voice in making the big decisions that affect them. The evident lack of concern for teachers throughout the discussions of school closures has been so sadly reflective of the disrespect afforded to the profession in this country that I supposed I shouldn’t be shocked.

Most of us, including the parents currently supervising the schooling of their children at home, do not have a great deal of insight into the demands of teaching. If we did, teaching would be among the highest paid professions in the country, without question. It is my hope that in the future, when COVID-19 is a memory and the economy is returning to life, the students who are now witnessing their teachers’ innovations are learning that actually no, not just anyone (your parents) can do what teachers do. I hope the respect teachers truly deserve will grow.

I hope eventually we will see clearly the sacrifices teachers made during this crisis (and the way they were sacrificed). I hope we start to understand how important teachers are, and value them enough to stop sacrificing them in the name of economic gain. I hope, ultimately, those exhausted teachers sitting quietly in my webinars will, at last, receive the respect befitting their status as some of Australia’s most essential workers.

Dr Amy McKernan is an early career academic at the Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne. Her research broadly investigates teaching and learning with confronting histories and narratives of trauma, violence and injustice. She is a teacher educator in the sociology of education, international education, and educational research methodologies.

Back to top

So what does “mass schooling” mean to us now?

By Nicky Dulfer

For the first time in my living memory, onsite school attendance has had to cease. Mass schooling, which has been described as a way of providing universal educational access through school attendance, has been disrupted in Australia and around the world.

We have closed schools and opted for distance and remote learning models to help contain the spread of COVID-19. For the vast majority of our 3.8 million students, this involves students attempting to learn in their home environments with their teachers providing content, support and feedback remotely.

As a result of school closures in Australia many people are just discovering how many roles schools fulfil. To students in unsafe homes, schools can provide sanctuary; to the hungry, food; to the homeless, shelter; to the scared, security; to the lonely, friendship; and to the isolated, a sense of belonging. For those of us who have worked in disadvantaged school settings this is not surprising. Schools have long been a proxy home for many students. School libraries can create safe places to sit quietly and read, school breakfast clubs can ensure everyone has the chance to eat something at the beginning of the day, school homework clubs can provide equipment and staff to support students who need some extra help, and school teachers can provide a valued adult relationship for students who seek connection and support. This is not to say that everything about mass schooling is positive.

To many students attending school can mean isolation, bullying, violence and ridicule. It can mean being taught to be ashamed of personal cultural heritage and difference. It can be a place that is not safe or inclusive. For many students, schools are just another place in which they are not valued.

Mass schooling has meant that schools are also often sought after as places to institute certain political agendas. Governments have long understood this. In the 1970s the Whitlam government instituted the Disadvantaged Schools Program as a way of ensuring schools could help support those students who needed it most. Until the 1980s students used to sing ‘God Save the Queen’ at every assembly as way of ensuring the Colonial past erased all that had gone before. The Howard government offered additional financial support to schools if they flew the Australian flag. Mass schooling is also seen as a way of instituting social agendas as schools are a way of reaching all students. In the 1950s the Menzies government, concerned with malnutrition among children, instituted the school milk program. In the 2000s concerns around obesity led to significant changes in what is available at the school canteen. Now, students all around the world are being educated on the correct way to wash their hands in classrooms.

Thus, school sites are often used to perpetuate both helpful and harmful political and social agendas.

In the time of COVID-19 one thing that has become very clear is the dependence of modern society on mass schooling. The provision of mass schooling serves the dual economic function of allowing parents to work whilst educating their children to be useful to the workforce in the future. It also serves the social function of transmitting the social norms of society to students. Additionally, mass schooling has been used as a place in which equity has been supported.

I believe one of the few good things to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic is the revitalised conversation within our communities about what it is that mass schooling does, can and should do.

Nicky Dulfer is a Senior Lecturer at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne. Her research areas of expertise include issues of inequality and pedagogy within secondary education.

Back to top

Saving education: Trust me I’m an expert

By Jessica Gerrard

Dr Norman Swan comes on the radio and I shush my partner. Dr Norman Swan has become a national treasure.

COVID-19 is apparently going to save experts. After years of the apparent growth of ‘populism’ and of the political denial of climate change, it appears it has taken this horrendous virus to demonstrate the utility of expert knowledge.

In the absence of political leadership, in the days and weeks after COVID-19 made its way to Australian shores, it was Dr Norman Swan – ABC Radio National’s health editor – who interpreted and disseminated the medical evidence on COVID-19. It is, of course, experts who are racing to find a vaccine and providing medical care.

Meanwhile, the Australian government has kept universities out of its cornerstone JobKeeper policy, throwing casuals – and the higher education sector – to the curb. There’s even reports of universities asking volunteers to cover teaching because of staff cuts. For permanent staff workloads have increased and universities (and the sector’s union) have already put pay slashes on the table.

In these sorts of moments, a defensive move is understandable: we have to save education, right? Higher education, after all, is the place in which experts are produced. And isn’t now, of all times, the time to be protecting and nurturing the production of expertise? Defending the worth of and possibility for education for our future?

Expertise, however, is neither neutral nor categorical. Experts do not float disinterestedly above social relations. They are made by society and they have a vested interest in making particular versions of society. Eugenics, phrenology, conversion therapy, hysteria diagnoses – and dare I say it, even JobKeeper – were all driven to some degree by experts.

Expertise rests upon divisions between experts and so-called ‘laypeople’, and this division is marked by power. It also rests upon structural inequalities of education. Despite the vast expansion of higher education, contemporary society is built on a fallacy, not actuality, of social mobility for all. Hierarchical divisions in educational achievement are the bedrock of educational institutions, as are inequitable divisions in labour.

COVID-19 is apparently going to save experts, but it is cleaners who are saving us all.

Expertise is not just about producing knowledge: it is also practiced in relation to the ‘unknown’. The boundaries between the known and unknown are shaped by what we think it is possible to know about; what the social, technological and political relations of the day make possible to know about; and what is strategically denied (*cough* climate change).

COVID-19 demonstrates that the current moment is not defined by a withering of expertise, but its reconfiguration in relation to what is known and unknown (and asserted to be known and unknown) in the function of modern capitalist democracies.

Indeed, the recent proposals that materially de-value the humanities and social sciences demonstrate that the current Australian government is centrally concerned with the form and function of expertise. In this proposed reform particular forms of expertise are recognised as valuable above others.

Moreover, it’s no coincidence that at the time of rising post-truth there is concurrent fetishization of evidence and data. Particularly in education, data metrics are increasingly valued political assets: university and journal rankings, student evaluation surveys, impact scores, citation rates, h-indexes are all presented as numerical proxies for the value of university work.

So, what exactly are we saving? What education are we declaring an interest in for the future?

Perhaps at the very least, not one that unthinkingly asserts expertise as an unproblematic elixir. And not one that presumes that the production of expertise necessarily relies on divisions in labour and systems of meritocracy that structurally require unequal access to education and outcomes of it.

Shush, Dr Norman Swan is back on the radio.

Dr Jessica Gerrard researches the changing formations, and lived experiences, of social inequalities in relation to education, activism, work and unemployment. She works across the disciplines of sociology, history and policy studies with an interest in critical methodologies and theories.

Back to top

Ancestral 2020 vision: Chronicle of a death foretold

By Ligia (Licho) López López

Part II

Wati’t, will you tell me the rest of that origin story?

The one where another life begins in the future.

Right. The story of a future inhabited by peculiar beings who will call themselves Humans. Thousands of years from now, in the year 2020 entities from the virus world will decimate thousands of them. Humans will be forced to flee. They will mistakenly think of the virus in the only frame they know: War. So in the first months of a rising decade in the 21st century, they will wake up and will feel as if bombs were dropped on them as they have dropped bombs on others. With no time to pack their bags stuffed with Human supremacy, and the rest of their useless belongings including belonging itself, they will lose being and becoming Human.

What will those planes of existence look like Wati’t?

Full of wonder and wilderness! At first they will be afraid of what they will encounter. With no Normal saint or Economy god to misguide their existence, they will be swept with bewilderment. The first thing they will realize is that they are just one more element of an endless constellation and not the centre of it. Some of the cleverest ones, well they will not be that clever, really! but some of them will smuggle their useless concept of the Individual which will have no currency in other planes. Their existence will be relational. Upon entry to these unfamiliar planes of existence, Humans will disappear and become a collective of moving particles. Friction, magnetism, and sonic waves, not Identities, Borders, or Institutions, will characterize their movements in the new planes.

Remember that genius Human invention they called Schools? Well before being forced by the 2020 virus entity to flee the world as they knew it, Schools were Institutions. In these planes Schools will be sites of encounter. They will be located throughout and will not require a building called “school” for learning to take place. Because some habits are hard to die, some of them will invoke obsolete modern ideas to say “schools are the best place for children to learn.” But the majority of them having learned the lessons from the 2020 pandemic will ask: To learn what? To learn how? To learn whose knowledges? Can knowledges be owned? What counts as learning? What learning counts? Where, with what, and with whom can learning take place? In the new plane of existence, they will realize that moulding children into rubrics, test scores, statistics, international comparative data, and the next capitalist battalion of citizens will bring their demise. It will by 2020 and will again after 2020.

Instead of learning to become settler colonialists, at the site of encounter children will teach and learn about colonialism and the history that forced them to seek refuge in new planes of existence. Instead of taking, children will learn to borrow and give back in full respect of the sentient beings they will be in commune with. Children will return to their wilderness without the Human fear of “being backward” or “falling behind.” That will be pre 2020 history. Colour codes for children’s bodies will no longer be the norm. In fact, there will be no norms, gender or otherwise. There will not even be ‘children’ as the category upon which ‘adults’ manage and attempt to control the/their futures. Through wondering into the histories of human grids and classificatory regimes through online or VR learning, they will regain a sense of humility. That will be the ultimate social and emotional learning lesson resulting in new worlds unfolding. How marvellous!

Maltyox wati’t

Dr López López is a Caribbean, Queer, and Brown scholar of Indigenous background whose life begins in Abya Yala. She has lived, researched, taught, and learned in continental Africa, Europe, the US, and Australia. Her interdisciplinary research is situated at the intersection of curriculum studies, Indigenous and race studies in education, and youth and visual studies.

Back to top

By Sophie Rudolph

On my daily local walk I pass a primary school which now has a sign on the gate saying there is limited access to the school while remote learning is in place. The ‘learning from home’ situation has meant parents and carers have been asked to supervise and facilitate learning that is set out and guided by teachers remotely. Teachers have been asked to transform their lessons and connect with students and families in unfamiliar ways, many going to extra lengths to reach those who have limited digital resources at home.

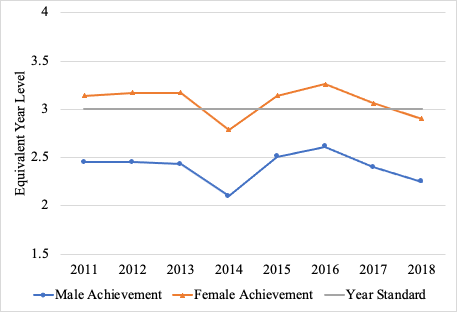

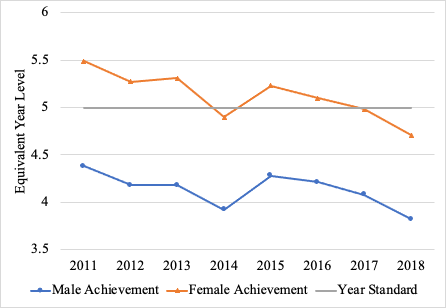

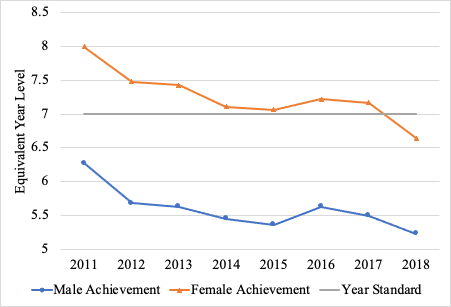

In recent decades education has become highly focused on the product of learning – NAPLAN results, PISA results, ATARs, marks and degrees are tallied, scrutinised, lamented, celebrated and compared. This focus on product both overshadows the process of learning and undermines education as a social good – in and of itself valuable. It can easily position teachers as technicians and students and parents as consumers, concerned primarily with their own individual success. However, education is much more than this and rarely is the lived reality of education so stark and straightforward.

During the COVID-19 pandemic children and young people have been frequently positioned as an inconvenience – the supervision and care they require being seen as an impediment to ‘restarting the economy’. The government was quick to push for learning to be transferred back to schools so that parents/carers can be freed to return to their roles within the economy. However, this overlooks the unpaid and underpaid labour that is done under regular circumstances to support the economy.

The lessons of this time therefore offer opportunities for valuing and nurturing some of the parts of education that have been disregarded by the shift to focus on educational product. A post-pandemic education system could take seriously what feminist global studies historian Tithi Bhattacharya argues are the ‘life-making’ activities of social reproduction. This is work that is largely done by women or in highly feminised professions and it is work of a social nature, not purely an economic nature. It is the process and relational aspects of education, not the product. Imagine if we thought about children and young people as important, thoughtful and valuable members of our society now, rather than just future workers getting in the way of the economy.

If education were to value community more thoroughly, we might see greater time in schools spent building relationships with local First Nations communities to nurture understanding and awareness of Indigenous knowledge. We might see teachers, students and local community collaborating more to find solutions to problems affecting their communities. We might see curriculum that valued the funds of knowledge that children and young people have for pursuing their learning outcomes rather than waiting for NAPLAN or ATARs to tell us what students can and can’t do. We might recognise that the job of teaching involves emotional work and that teachers require time to recharge so they don’t burn out and leave the profession. We might think about restructuring work so that communities – teachers, students, families, carers and friends – have more time to come together more often to share in the process of learning and living together.

We could take a lead from young people who ask us to imagine what is possible, and work collaboratively to cultivate education communities that care for the human and more than human world, and not just for their ATAR outcomes and unfettered economic growth.

Dr Sophie Rudolph is a Lecturer at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education at The University of Melbourne. Her research and teaching interests centre on issues of education equity, politics and ethics, through historical and sociological analyses.

Back to top

Turning global adversity into advantage: Working towards education for all

By Rhonda Di Biase and Bonita Cabiles

When listening to an expert panel talking about COVID-19, one particular comment resonated with us: “We will learn a lot about the virus, but we will learn more about ourselves”. The subsequent discussion referred to our learning as people, as communities and as nations. We add to this, learning as a global community, and we reflect on this here.

In discussing the race to find a vaccine, this same panel highlighted differences in the way this particular global challenge has resulted in an international collective effort. A spirit of collaboration, not competition, has developed in the race against the virus. Can this global momentum to collaborate be harnessed in new and creative ways in a post-COVID world?

So too does this question apply to our vision for the world we want post pandemic. Can we continue to work together in unprecedented ways? Can our common goal become to realise the vision embedded in the United Nations’ globally endorsed Sustainable Development Goals?These goals include no poverty, zero hunger, good health and wellbeing, quality education, gender equality, and reduced inequalities. This pandemic provides impetus for a more deliberative discourse around issues of equity in education, including how we ‘do aid,’ without reverting to business-as-usual. The vision embedded within the Sustainable Development Goals offers fertile ground for international interdependence working towards education for all.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced a disruption to the status quo of schooling that has exposed more sharply the cracks of education, especially among the most vulnerable. It has powerfully cast a bright light in many countries on what seems to be a perpetual state of crisis in education.

However, financing, which is a key to bridging educational inequities, remains compromised. In the latest UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report, Sustainable Development Goals Secretary-General, Jeffrey Sachs, laments the sobering decline of development aid for education. In the aftershocks of COVID-19, will the global community be willing to work in a spirit of cooperation to ensure equitable education for all; or do we, instead, become inwardly focused and leaner and meaner as nation-states?

Our question is not unfounded. In news about international cooperation in developing a vaccine for COVID-19 the focus of discussion is already around who or which countries will get access. Will access to any successful vaccine depend on money or kindness, on power or a sense of equity and justice? We ask similar questions about education and aid. We fear that as countries tighten their geographical borders and focus on impending recessions and debt and deficit; the sense of compassion, care, and solidarity may also end within their borders. Low and middle-income countries, after the pandemic will, more than ever, need to work within a global community as they advance their respective national/local agendas of equity, justice, and inclusion in education, that have been exposed through this pandemic.

Local contexts offer extensive experiences and knowledge about how we can (re)think and (re)imagine collaboration to respond to and acknowledging the long-standing educational crisis that COVID-19 has pushed us to confront. Within this discourse, perhaps it is also time to foreground the voices of the local communities to construct ‘glo/b/cal’ cooperation, whereby local conditions are centred in global initiatives and international development.

Rhonda Di Biase is a lecturer at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne. She is currently a co-convener for the AARE Global Contexts for Education SIG. She has previously worked at the Faculty of Education, Maldives National University as part of a post-tsunami aid project focusing on implementing student-centred learning and through an Endeavour Executive Fellowship. Her research interests include active learning reform, teachers’ professional learning and education reform in small states.

Bonita Cabiles is currently a PhD candidate at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne. She is currently a co-convener for the AARE Cultural and Linguistic Diversity (CALD) SIG. Her work explores issues of diversity and power in classroom practices with interest in Bourdieuian sociology and qualitatively oriented research.

Back to top

Which boat were you in?

By Michelle Cafini

American evangelical Christian pastor, Rick Warren, in his video, ‘Ten COVID commandments for emotional health’ states that long after a vaccine has been developed, people will still be dealing with the economic, relational and emotional effect of the virus. His words resonated with me when he said although we have all been in the same storm, people have been in different boats during the storm. Some in yachts, where they have had enough money, a secure job and a nice home to live in during the crisis. Some have been in rowboats, living week to week off savings and where being jobless has been a disaster. Others have been clinging to driftwood, experiencing homelessness, domestic abuse, and alcoholism to name but a few of the consequences of COVID-19.

As schools across the nation begin to re-open after a period of online learning, and staff busily adjust back to face-to-face teaching, it is important to reflect that things will not be “the same” as before. Teachers will be considering the social and emotional wellbeing of their students as they re-commence schooling in person. Things will not and may never be the “same” for some students. The experiences that students have had over the past few weeks and months will be different. While some students may have thrived at home, for others there may be deep emotional scars that may take a long time to heal – the death or illness of a family member, the arguments overheard between parents dealing with the ramifications of unemployment, increased alcohol consumption in the home, anger and abuse that manifested while families were in lock-down, the loss of self-esteem and social skills that are usually being developed during interactions with friends. All of these factors may have a considerable impact on the lives of different students, and the once happy, resilient, confident student in January may not present in the same way in July.

School leaders and teachers will be mindful of the boat their students have travelled in during the storm and may need to provide support for those who have lost their bearings. More than ever, embedding social and emotional learning into the curriculum is important. Young students who were just starting school may need support to foster friendships. Those who have spent lengthy time with caregivers may feel the anxiety of separation and will need to once again develop confidence and trust at school. Students who were just in the throes of transitioning from primary to secondary school and only just adapting to new expectations and routines may need to be assisted to develop social and self-management skills. And those at the end of their school journey may need the motivation to set course again. While many teachers would have been cognizant to look out for this at the beginning of a new year, teachers will be observing their students through a new lens, knowing that the experience of isolation will have had some impact – for some positive, for others not.

When the bell rings, it will never be back to the way it was. When the boats come back into the shore and schooling resumes in its entirety, teachers will be confronting the journey each child has been on. School may be the safe harbour that many of them are needing.

Dr Michelle Cafini has recently commenced employment at the University of Melbourne, teaching units in the Master of International Education (IB). She has over 30 years of experience teaching and leading schools in Victoria and overseas.

Back to top