Noella Mackenzie and Martina Tassone explore structured literacy, whole language and balanced literacy. This is the fifth post on reading to celebrate Book Week. What we’ve covered so far:

One: How to find your way through the reading jungle

Two: What really works for readers and when

Three: What is the Simple View of Reading?

Four: What is the Science of Reading?

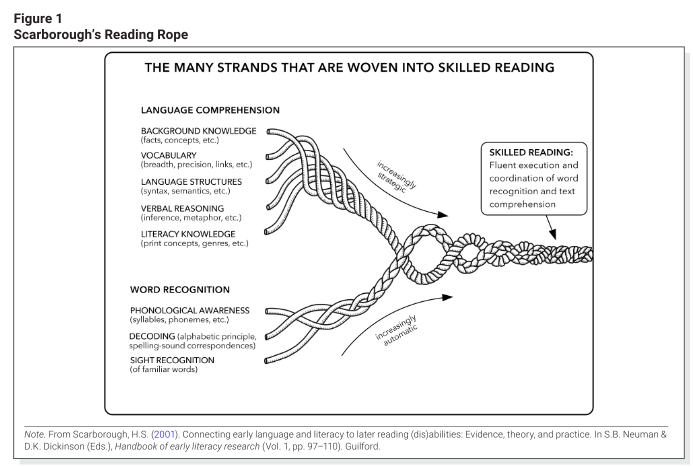

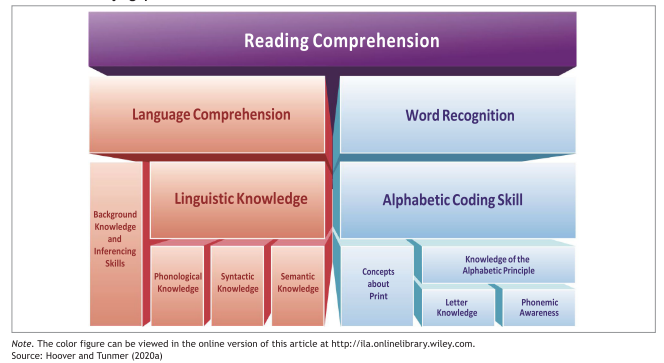

Reading models do not automatically translate to classroom practice. Instead, it is the knowledgeable and skilful teacher who translates models or theories into classroom practice. A teacher’s beliefs may steer them towards a particular model or theory.

For example, teachers who believe reading for meaning is critical at all stages of reading, are more inclined to align with a model that embeds meaning throughout all stages of instruction. In contrast, a teacher who believes decoding is at the heart of reading, will align more comfortably with a model or theory that requires a strong emphasis on phonics and decodable text use.

The reality of Australian classrooms

The teacher who has access to multiple models and a range of possible pathways, can work flexibly. This caters for the diversity of students that is the reality of Australian classrooms in the current landscape.

Key features of Structured Literacy (SL) are identified as:

‘(a) explicit, systematic, and sequential teaching of literacy at multiple levels— phonemes, letter–sound relationships, syllable patterns, morphemes, vocabulary, sentence structure, paragraph structure, and text structure; (b) cumulative practice and ongoing review; (c) a high level of student– teacher interaction; (d) the use of carefully chosen examples and nonexamples; (e) decodable text; and (f) prompt, corrective feedback’.

However, SL appears to apply ‘principles of industrial production: linearity, conformity and standardisation’ at a time when we should instead be promoting ‘a creative revolution in education’. Structured Literacy (SL) is a term often used by commercial phonics programs designed for children with dyslexia or reading difficulties.

Commercial programs in question

The quality of commercial programs has also been questioned. Researchers examined over 100 Commercial phonics programs and found considerable problems. For example:

- One program introduced the sound /t/ but then provided a follow-up activity that featured words in which the /t/ phoneme did not occur, for example the word ‘the’.

- Another example was an activity where children had to identify words that commenced with the /æ/ phoneme such as ‘A’ for apple, but also included images representing words that do not contain /æ/, as in ‘A’ for apron.

Researchers were also concerned that the linguistic inaccuracies in some of these programs could confuse both teachers and children. Some also used gimmicks and avoided using correct terms to describe phonemes-graphemes. An additional concern was raised about commercial programs used in pre-schools. It required children to engage in ‘busy’ work, such as colouring in worksheets, as well as drill, practice and memorisation. The ‘individual needs of students and the professional autonomy of teachers’ are de-centred by commercial programs .

There is no research to demonstrate the benefits of SL scripted programs for mainstream classes . There is no research to demonstrate the benefits of SL scripted program for typically developing readers who make up 85-90% of students in most classrooms. SL programs are designed for the 10-15% of children experiencing learning to read difficulties.

Why our students need skilled teachers

We believe students need knowledgeable and skilled teachers who can create differentiated teaching opportunities to meet the needs of all children; commercial programs simply cannot provide this.

Whole Language instruction refers to an approach which focuses first and foremost on whole texts. It uses these to teach the small parts of language, including words and letters. In the 1980s and 1990s, whole language was a growing movement of teachers, bearing affinities with learning centred, literature-based, multicultural classrooms in the UK and other parts of the English-speaking world including New Zealand and Australia. Whole language teachers use authentic texts or trade books (children’s/ Young Adult fiction, non-fiction, poetry, magazines, etc.) and children’s writings rather than readers and textbooks.

Some advocates of whole language believe that “for some children, a minimum of teaching, and sufficient exposure to print supported by interaction with more advanced readers including family members, is enough to learn to read”. However most children will need explicit instruction to learn how to read.

Whole language is sometimes incorrectly confused with balanced literacy

Balanced Literacy (BL) describes an approach used by many teachers in Australian classrooms until recent policy changes. BL continues to be the dominant approach in Canada, continually successful on the international literacy stage. However Ontario has recently added a Synthetic Phonics element to their curriculum. A Balanced Approach is also common in the republic of Ireland, which consistently does very well in international assessments. The term ‘balanced’ is used to describe how a knowledgeable teacher works to respond to constantly shifting student needs, in the day-to-day teaching of Literacy. There are five ways to balance literacy learning:

- Balancing reading and writing,

- Balancing phonics and comprehension,

- Balancing Informational texts and Narrative texts,

- Balancing direct instruction with dialogic approaches, and

- Balancing whole class instruction and small groups.

BL also offers a teacher a way of being able to cater for the diverse needs of their students. BL classrooms also focus on oral language and include shared reading, guided reading, independent reading, read aloud and writing activities that help students make connections between their reading and writing.

A brand new model

The Double Helix of Reading and Writing is a new instructional reading and writing model. The authors argue that their “model provides a rationale and evidence base for a balanced approach to teaching reading and writing . . .[and argue that] the practice of systematic phonics teaching should be carefully integrated with other main elements in reading and writing lessons and activities in early years and primary education”.

Tomorrow: the impact the media has on the teaching of reading

Noella Mackenzie is an adjunct associate professor at Charles Sturt University. Her areas of research and expertise include the teaching and learning of literacy. Martina Tassone is a senior lecturer in teacher education at the University of Melbourne. Her research interests include literacy teaching, learning and assessment in the early years of schooling.