Day Three (counting the pre conference day), December 3, 2024.

Table of contents

- Housing affordability and the teacher shortage

- An exploration of the use of AI-embedded Augmented Reality Glasses on primary student learning experiences

- Courageous and collaborative. Above all, hopeful

- Symposium – AI system development and validation for educational and career pathways

- From hip-hop to the Barrier Reef – culturally and linguistically diverse education

- Blak Out Tuesday

- Vox pops*

- Structurally adjusted: An analysis of the Mongolia education policies on teachers following the transition to democracy

- Making educational change with silent dialogues and methodological intimacy

We will update here during the day so please bookmark this page. Want to contribute? Contact jenna@aare.edu.au

Our EduResearch Matters social accounts are:

Housing affordability and the teacher shortage

This post is by Scott Eacott, UNSW

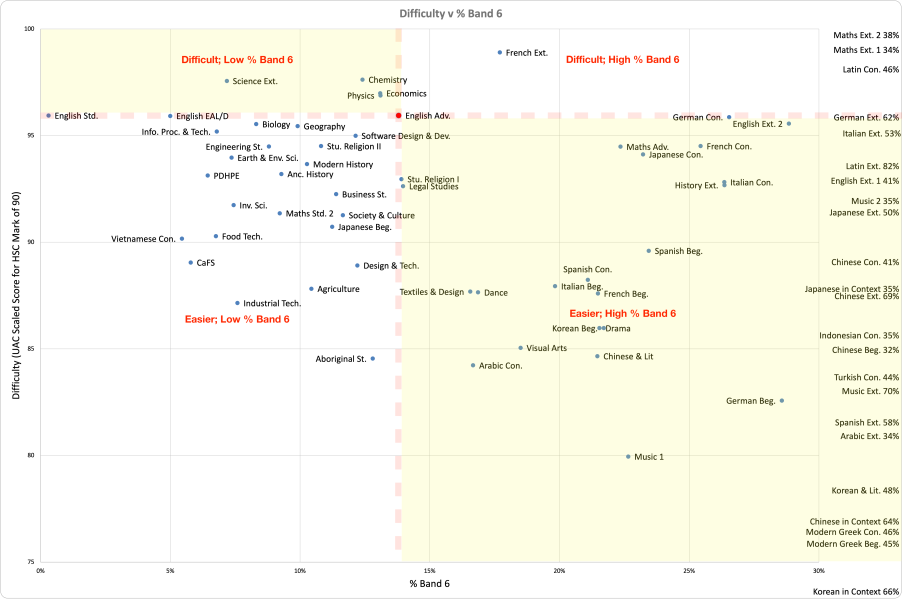

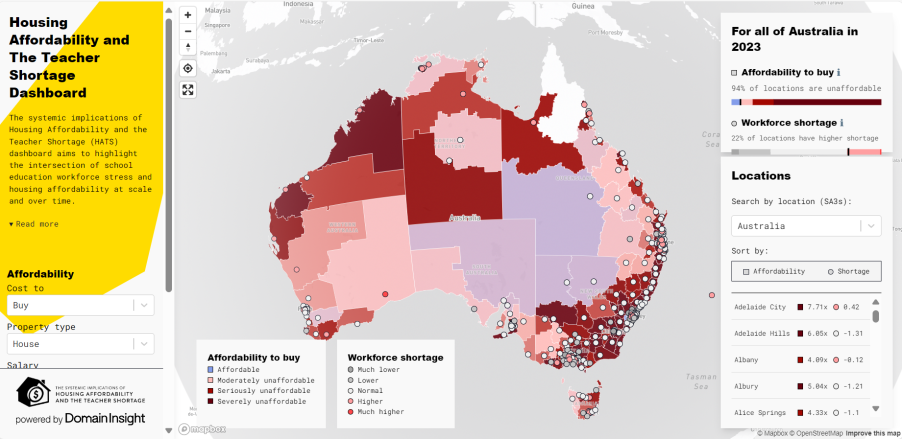

As part of a symposium on geospatial analysis in education, I introduced the Housing Affordability and the Teacher Shortage (HATS) dashboard.

Developed in collaboration with Small Multiples, and powered by Domain Insights, the HATS dashboard aims to highlight the intersection of school education workforce stress and housing affordability at scale and over time. It uses large-scale administrative data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), and Australian Property Monitors (APM), and standard metrics of affordability such as Demographia housing affordability ratings, and the threshold levels used by the Rental Affordability Index (RAI) published by National Shelter, Community Sector Banking, Brotherhood St Laurence, and SGS Economics & Planning.

The dashboard enables users to toggle between renting or buying, units or houses, and for graduate or top-of-the-scale teacher salaries over the period 2011-2023 (with annual updates planned), at the Statistical Area 3 level. In doing so, it is not limited to any one sector or state / territory.

It is important to note that the HATS team recognises the complexity of housing affordability and school education workforce issues, and that the dashboard provides best estimates based on the data available and it is only one source of information to inform ongoing debates. At the same time, it is a useful conversation starter for looking at longitudinal trends in median sales and rental costs for the teacher workforce. As teacher salaries struggle to keep pace with housing costs, and the availability and quality of teacher housing remains problematic, tools like the HATS dashboard can help government, stakeholders, systems, and educators to better understand how best to meet the needs of the profession.

An exploration of the use of AI-embedded Augmented Reality Glasses on primary student learning experiences

This blog is by Steven Kolber, University of Melbourne

Presenters: Gretchen Geng, Flinders University; Amanda Telford, Australian Catholic University; Kathy Green, Australian Catholic University; Yue Zhu, Zhejiang Normal University; Ningqing Liang, Hangzhou Lingban Technology Co., Ltd (ROKID); Zhou Yueliang, Zhejiang Normal University

Gretchen presented on a large collaborative research study which will continue to develop over the coming years. Flinders University, ACU and Rokid are collaborating to make this an ongoing reality.

The distinction between AR: Augmented Reality, where additional information is overlaid onto a view of the real world.

VR: Virtual Reality is where a person is consumed by the focus of a virtual reality, and they are disconnected from the ‘real world’.

VR is not ideal for young students, because that cannot clearly differentiate between the real and the virtual worlds at such a young age. AR however can be used as a learning tool as students are still engaged with their lived reality.

Students might be bored by, say dinosaur fossils in a museum, but through AR goggles they might actually begin to see what these dinosaurs looked like when they were alive. And make the space of a museum more engaging through this new emerging technology. AI allows for communication with the goggles themselves as a possibility for further learning avenues.

Using seven primary school teachers from two schools, researchers and teachers co-designed lesson plans to suit their student cohorts. Students are able to interact with the virtual world through different types of ‘embodiment’, such as grabbing and grasping virtual objects. The question being explored is whether these embodiments are different to those accessible via say an iPad or laptop.

Teachers and students were learning alongside one another, and the goggles can be linked to a TV at the front of the class so that the remainder of the class can follow along with.

Another project looked at ‘smart dinosaurs’ where 100, year 1 and 2 primary students completed drawings before and after an AR learning experience. For example, the vast majority of students will draw a T-Rex as though they are the only example possible of a dinosaur. They learnt about the size of dinosaurs in comparison to themselves and of the diversity of these dinosaurs as a small example.

As you can already picture, this makes the classroom quite a different space, where students are engaged and excited about the interactive elements of this type of learning.

Courageous and collaborative. Above all, hopeful

Navigating Hope and Challenge: Leadership for Pacific Learners and Schools in Crisis

Presenters: Tufulasi Taleni and Mohini Devi

The following post is written by Mark LaVenia, University of Canterbury

The Conch’s Call: Leadership for Change

A resounding horn filled the room, its vibrations unmistakable—a call to action, unity, and reflection. This was the Foafoa, the sacred conch shell, heralding the start of Tufulasi Taleni’s presentation at the Australian Association for Research in Education conference. The conch, conceptualised by Tufulasi as the “Caller of Hope,” symbolises connection—bringing people together to address urgent and profound matters that impact the health, safety and wellbeing of the community. Tufulasi, a trailblazer in Pacific education from the University of Canterbury, invoked its sound to frame the session on educational leadership, shared with Mohini Devi of the University of Fiji.

Both presentations highlighted the transformative potential of leadership, with Tufulasi advocating for culturally grounded, proactive approaches and Mohini reflecting on the challenges of leadership in the face of natural disasters. Together, they offered a powerful exploration of how leadership can either empower communities or leave them adrift.

Untangling the Tangled Net: Tufulasi Taleni’s Vision

Tufulasi drew from his Samoan heritage and decades of experience to present a framework for leadership grounded in Pacific cultural values. His Soalaupulega Samoa Theory (SST) is inspired by the traditional Samoan practice of Matai (chiefs) collaborating to solve community challenges. It is both culturally rigorous and solutions-focused, tackling the systemic barriers that hinder Pacific learners’ engagement and achievement.

Using the metaphor of a tangled fishing net—complex, laborious, yet vital— Tufulasi explained the urgent need to untangle the educational challenges facing Pacific students in New Zealand. These include cultural disconnection, systemic inequities, and the erasure of Indigenous knowledge. Effective leadership, he argued, is relational, optimistic, and visionary. Leaders must “lead from the front,” nurturing new leadership while aligning school cultures with the identities and aspirations of Pacific learners.

Timidity in the Face of Crisis: Mohini Devi’s Findings

In contrast, Mohini Devi’s research examined the preparedness and responses of school leaders in Fiji to natural disasters. Through interviews with leaders across diverse settings, she painted a picture of unpreparedness and systemic constraints. Leaders often lacked comprehensive disaster plans, adequate resources, and the confidence to act autonomously, leaving them reliant on government directives.

Mohini’s findings revealed a troubling timidity—a reluctance to step outside comfort zones or take risks on behalf of their communities. The cascading effects of disasters, compounded by emotional and psychological tolls, highlighted the critical need for resilience, communication, and proactive leadership.

Leadership at a Crossroads: Hope or Hesitation?

The two presentations, though focused on different contexts, converged on a crucial point: leadership matters. Tufulasi’s framework embodies strong, culturally rooted leadership that prioritises community wellbeing and educational equity. Mohini’s study, on the other hand, underscored the consequences of a leadership void—where inaction and dependence on external authorities stifle progress.

Together, they prompt a reflection: How can leaders move beyond timidity to embrace their role as navigators of hope and change? As Tufulasi’s metaphor of the Foafoa reminds us, leadership is not merely about directing—it is about connecting, uplifting, and transforming.

Closing Reflection

The session left attendees with a resounding challenge: to reimagine leadership as a deeply relational, proactive force capable of addressing the tangled nets of systemic inequities and crises. Tufulasi’s call to action was clear—leaders must draw from cultural strengths and navigate with purpose.

For the Pacific and beyond, the path forward lies in leadership that is courageous, collaborative, and, above all, hopeful.

Symposium – AI system development and validation for educational and career pathways

This post is by Ben Zunica, University of Sydney

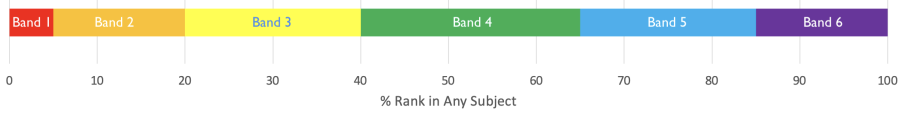

Jihyun Lee and Ali Darejeh outlined two projects they are working on that are centred around generative AI for advising students on their career pathways for students from Year 10 at school to University course selection and subsequent work places.

The authors have developed AI learning systems to support student career advising for high school students, as they are often unaware of their passions and the range of available options that are open to them. This learning system uses a combination of technology including Python and ChatGPT-4o-mini. The AI would help guide them to choices that are aligned to their aptitudes, interests and values. It is also anticipated that the AI system will provide a more personalised service than traditional online job quizzes.

The system was tested with 20 participants aged 18 – 25 years of age. Participants reported that the AI support system was well received and was superior to online job quizzes.

The presenters went forward to discuss their second project, using AI to predict student admission to medical school, which was developed using what previous research suggests is most pertinent to the outcome of admission. They showed a video demonstration where the user inputs data and then predicts whether they would get into medical school and then gives the user feedback on how they can strengthen their application. They tested on past applicants who were accepted and rejected. Findings showed that the participants who used the system enjoyed using it and found it was helpful in advising them on whether medical school is an option for them.

There are some limitations which include the small number of participants and the difficulty in developing prediction systems, as humans are unpredictable and statistical prediction is very challenging.

This presentation showed the ability of generative AI in helping students at high school and university find career paths that are open to them and fit their particular tastes.

From hip-hop to the Barrier Reef – culturally and linguistically diverse education

This post is by Mutuota Kigotho, University of New England

Gabrielle Morin presented her research on sex education in New Zealand. The research used decolonial methodologies to investigate how sex education fitted within the curriculum in New Zealand. Students found the method responsive to the content being taught. Other methods used included the use of hip-hop to access content.

Mutuota Kigotho presented on ways in which Tim Winton has used fiction to sensitize readers about the Australian landscape, Australian lingo and Australian history. Tim Winton also presents his work that addresses environmental protection, saving the Great Barrier Reef, the Ningaloo Reef, as well as getting Australians to stop dangerous activities such as coal mining in Australia. Tim Winton has shifted his focus to making documentaries to pass his message. Artists need to do more to save the world from the damage inflicted on the country by big multinational entities.

Radha Iyer has used the theory of Practice Architectures to work with her Cultural and Linguistically Diverse students at Queensland University of Technology. She has found that students are more comfortable when content is presented in discourses that are culturally acceptable and in a language that is tailored to assist them particularly when they have only recently arrived in Australia. Some say that terms such as ‘pedagogy’ are new to them and yet lecturers may take such matters for granted.

Blak Out Tuesday

What does school reform in the best interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children look like? Sustained whole-school change in schools

The following post is written by Naomi Barnes, QUT

Kevin Lowe, a Gubbi Gubbi man from southeast Queensland, professor and Scientia Indigenous Fellow at UNSW, got a standing ovation for his Blak Out Tuesday keynote. Blak Out Tuesday is where AARE showcases Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander excellence in education research.

Lowe’s keynote address comes after more than 40 years of disappointment with the lack of progress across all education systems to effectively enhance educational quality and engagement for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students.

While policy failure is pervasive, there is no shortage of evidence about what could improve Indigenous educational attainment. Lowe explains that he is not ever going to say anything new but that he is repeating what has always been known. It is not like Indigenous people are asking for something unusual. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people want to read and write, find success and access the resources that enables them to have a happy life. That is not asking for too much.

Lowe asserted that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people also need representation in schools and administrative roles – ‘to have black faces in the schools working with us and alongside us’.

Statistics of attainment for Indigenous children in Australian schooling have always been a failure of promise. The failure of the Closing the Gap promise is a $40+ billion failure. Where has that money gone? How could taxpayers in this country allow this to happen?

Lowe, a great believer in research (but what research for who and how?), took us through his career of working to improve outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education. He has seen lots of success, but they all fell over because once success was shown, the money was withdrawn and given to another program. Despite this policy funding failure, Lowe noted 5 things common to all successful programs. None of them are new:

- Genuine engagement and acknowledgement of community

- Teachers using impactful practices that are culturally responsive, relational and engaging

- Student identity, language, culture agency and well-being is valued

- Active and shared leadership in teaching and learning

- Value Indigenous knowledge in curriculum and pedagogy

This is complex work. It is not easy. There is no silver bullet because the work of being a teacher of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children is undoing centuries of policy which has isolated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from the school system. The core element of this moral and social enterprise is to support the development of collaborative relationships between teachers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, families, and communities.

Culturally nourishing schools research points to solutions, and in particular, the need to affect systemic and school change, coupled with local relationships and educational governance to form the foundation of a more equitable and responsive education system- one that nurtures the potential of every student and speaks directly to the aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Vox pops*

Stephanie Milford, PhD student, Edith Cowan University (pictured, left), spoke to AARE’s roving interviewer Margaret Jakovac, PhD student from Deakin University. Margaret is around the conference talking to people. Here’s our first one.

*Vox pops are on-the-spot interviews.

What did you take from the pre-conference keynote presentation about generative artificial intelligence (AI)?

“I remember attending the AARE 2022 conference and the buzz around the then new generative AI called ChatGPT. Now, I use it for my PhD in small ways. For example, I use R for computer programing and when there’s an issue, I just put my code in ChatGPT and it will find the missing apostrophe that would have taken me half an hour to find.

“The gen AI presentation provoked critiques about the role of AI for us educators. I’m all for AI, but it has to be used ethically.

“I try to get my students [at university] to self-reflect just subtly when I think they’re using AI. I’ll say, ‘if you have used AI, it’s essential to put in a reference’. Or I ask them if their assignment they’ve handed in is how they normally write.

“These issues in a way link to my PhD research, which was embedded in digital literacy – parental mediation of device use in children. Parents face conflicting messages: Health advice is antiquated and talks about restricting screen time, taking a harm minimisation approach. But what are students using digital technology for in schools and at home – it can be for productive time. There’s a need for consistent and non-judgmental advice for parents. Maybe for educators and those who educate pre-service teachers, too.”

Structurally adjusted: An analysis of the Mongolia education policies on teachers following the transition to democracy

This post is by Jason van Tol, University of Technology Sydney

Key takeaway points for me from this presentation by Usukhbold Chimegregzen were that while Mongolia was a state socialist country based on subsistence agriculture and animal husbandry from 1921-1990, it implemented ‘democratic’ reforms from 1990 onwards, based on conditions of loans taken from the IMF, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank (ADB). These conditions addressed all facets of social and economic life, including education. One of the effects of these reforms, or “structural adjustments”, was that 30% of the most senior teachers, amounting to 8000 teachers, were “eliminated” (ADB’s term) from the workforce to pave the way for the indoctrination of a new wave of young teachers to implement the new ‘democratic’ reforms, leading to vast increases in inequality, deprofessionalising teaching, and fomenting competition, both in schools and the wider society. Change in economic activity is that Mongolia’s economy is now geared towards exporting copper and coal, primarily to China and Japan. If Mongolians speak out about these ‘democratic’ reforms, they are labelled ‘communists’.

Reflecting on this presentation a few thoughts came to mind:

- The centrality and power of economic institutions (what Michael Hudson calls ‘finance imperialism’)

- The close relationship between education (i.e. schools and universities) and the economy.

- The use of political terms in transparently ideological ways to promote one set of interests (usually corporate ones) and to denigrate others (the common good). While a prima facie view may be that we in Australia are independent of this system of political economy in the Global South, as Jason Hickel has bluntly put it: accumulation in the core depends on dispossession in the periphery.

Finally, I’m thinking of Gert Biesta’s concept of ‘world-centered education’ and that nothing, at all, should be considered ‘off limits’ in education: if we are to understand the world, we must understand and teach about it in its totality.

Making educational change with silent dialogues and methodological intimacy

The following post is written by Junn Kato, PhD candidate, QUT

A Monday afternoon workshop conducted by Dr Sarah Crinall, Professor Mirka Koro, Associate Professor Jill Fielding, Dr Adele Nye, Professor Jennifer Charteris and Dr Angela Molloy Murphy invited participants to be silent on entry to a series of opportunities for entanglements arranged into stations around the workshop space. Drawing on feminist new materialisms, each opportunity offered an entanglement with not only creative materials of beads, wool, glue, lace, paper, texts, images, paints, but also matters of classroom learning and socially just practices as well as matters of social justice. Without a word being spoken, participants were guided, encouraged, playfully provoked and taught through patient and careful demonstrations, as well as opportunities to ponder with things. The multiplicative nature of the workshop meant that there is no single account that could contain or even summarise everything that occurred as a result, so I will simply share a couple of my entanglements and what they taught me.

I initially engaged with a station which drew attention to the terrible price paid by Palestinian children trapped in the Israel-Palestine conflict. The overwhelming volume of names printed on sheets took on more staggering proportions when activities for threading individual beads onto a string to form names, slowed down letters as they slid into place.

Sarah Crinall saw me stuck on this task, and offered a new provocation. A phone in a mug was placed in front of me, showing Mirka Koro on a Zoom call somewhere outside the room. Mirka very patiently guided me wordlessly and remotely through a weaving task I did not master, and I revisited my entanglements with young people who spent time on tasks they did not master. Perhaps I need to do things I find difficult, so I can remember how it feels to struggle, and in remembering, through my own practice, provide better care for those who struggle? At the edge of my peripheral vision, I was aware of colleagues’ becomings-with, their assemblages of texts and text leaving trails of doings, feelings, thinkings and beings across the walls of the room.

In my own research, I have adopted complex materialities as theoretical positions to trace the work of care. Yet this afternoon, applied as pedagogies, I learned how as material practices, these same ideas can be directly applied to produce a generosity in teaching that is about more, not less.