“We help you get started on your teaching journey in Australia”. — AITSL

Amid the 2025 federal election furor, migration became a central issue. Opposition Leader Peter Dutton proposed cutting permanent migration and capping international students. He blamed recent arrivals for pressure on housing, healthcare, and education. “Labor’s brought in a million people over two years”, he said, citing record migration and housing strain.

While Dutton stopped short of claiming migrants are “lowering standards”, his rhetoric mirrors a global trend in right-wing populism. In March 2025, the US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to dismantle the US Department of Education. He fulfilled a campaign promise to return school control to states—raising concerns over equity and federal support.

Both leaders framed migration as a threat to national capacity and cultural values. This revealed a deeper ideological project: the re-bordering of education under the guise of standards and control. Migration becomes a strategic focal point—mobilised to rally electoral support by casting it as both a cultural disruption and a structural burden to national institutions.

A more polished message

In contrast, the AITSL presents a more polished message: “Australia is popular for many things… a safe country with a friendly and relaxed culture… we can help you get started on your teaching journey”. Yet the AITSL portal also codifies a logic of superiority—positioning Australia’s education system as globally exceptional, its teachers as stewards of excellence, and its structures as the source of “evidence-based tools”.

This nation-branding rhetoric appears inclusive on the surface. But as our discourse analysis reveals, it constructs a one-way narrative of giving. Migrant teachers are positioned as beginners—“starting out”—even when they arrive with decades of experience. Their role is not to enrich the system, but to assimilate into it. As Mahati, a respected English teacher from India in Nashid’s doctoral study, reflected: “I had been teaching English for over twenty years across continents—India and Uganda—before I came to Australia. But here, I had to redo everything. It felt like I was invisible”.

The real costs are tangible. Laura, a cherished English teacher from the Philippines and participant in Nashid’s doctoral study, told us: “I took the IELTS test four times plus a review over two years. It cost me nearly four months’ salary in pesos. I had everything else ready—but the language requirement kept holding me back”.

Far from isolated

This issue is far from isolated. Migrant teachers frequently encounter inconsistent and retroactively enforced policy barriers. This occurs even amid a critical shortage of teachers and skilled migrants in education. While not representative of all, the stories of Amarjit, Anya, Reza, and others—such as Archana, Jigna, Joy, Hossein and his wife, Mahesh, Nishni, Samia, and Shurma—reflect recurring themes emerging from our shared work and Nashid’s doctoral research with immigrant teachers. Reza, a science teacher from Bangladesh, completed his Initial Teacher Education in Victoria. When he enrolled, the Victorian Institute of Teaching (VIT) required a lower IELTS threshold. But by the time he graduated, the benchmark had shifted significantly. “Academic IELTS: at least 7.0 in Reading and Writing and 8.0 in Speaking and Listening, on one TRF (Test Report From), taken within 24 months”.

An overall IELTS score of 7.5 or 8.0 can still be rejected if one skill—such as Writing at 6.5—falls below the required threshold. As scholars argue, this rigid, decontextualised format reflects a neoliberal and neocolonial gatekeeping logic. It marginalises qualified multilingual teachers through standardised measures detached from real-world communication.

Reza explained: “I kept failing. One time I got 8 in listening but 6.5 in writing. The next time it was the reverse. After two years, I gave up and returned home”.

One teacher’s journey

He continued teaching—at an international college in Bangladesh—while repeatedly sitting for the IELTS test. Over time, each attempt brought him close, but never across the threshold required by Australian standards. After two years of emotional and financial strain, his family suggested he apply through New Zealand. There a score of 7.0 across all bands was still accepted. He met the criteria, registered with the Teachers Registration Board of South Australia (TRBSA), and used this to apply for skilled migration with family sponsorship—gaining an additional 10 points. From there, he transferred his registration to the Victorian Institute of Teaching (VIT) and finally settled in Melbourne.

This narrative is part of a broader trend of policy drift: where teacher migration frameworks become increasingly exclusionary, often without recognising their global contributions, lived experiences, and situated knowledge of those navigating them. By contrast, NESA now offers more flexible pathways, including English testing exemptions for internationally trained teachers with relevant experience or English-medium qualifications.

State-level discrepancies

These state-level discrepancies expose a fragmented and inequitable accreditation landscape. Since 2022, our research and public engagement have informed national discussions and policy change. An article by the Australian Associated Press (AAP)—syndicated across 100+ media outlets— amplified the undervaluation of skilled migrant teachers, contributing to recent NESA reforms on English language proficiency test exemptions for internationally trained teachers.

Quang, a respected English teacher from Vietnam with four English-medium postgraduate degrees (two from Vietnam, two from Australia, including ITE/Secondary), shared a similar experience. “I passed everything—teaching practicum, assessments, I even got distinctions. But I still had to sit for another English test to register in NSW”.

This was only because two of his Australian degrees did not meet the four-year study requirement.

He started teaching as a CRT later. The principal introduced him to others by saying, “This is our new Vietnamese English teacher”. He wasn’t offended, even when told that others had laughed upon hearing that—but he understood what it signified.

“It shows what people expect: that someone like me isn’t usually seen as an English teacher”.

It’s not just language being measures

What’s being measured isn’t just language. It’s legitimacy. It’s the right to belong.

The AITSL migration guidelines suggest legitimacy flows from only a handful of countries—Australia, Canada, Ireland, NZ, the UK, and the USA—excluding many English-medium post-colonial nations like the Philippines, India, Kenya, Ghana, and Singapore.

Similarly, the “Teaching in Australia” guide constructs the ideal teacher through phrases like “Australian teachers must…”, framing competence as nationalised and native. Even appeals to “multicultural classrooms” fail to acknowledge migrant teachers as co-creators of this richness. Their linguistic and cultural knowledge is seen less as a resource, more as a hurdle.

This mirrors what Sender and colleagues call epistemic monolingualism: a worldview that centres standardised English and Western pedagogies as the only legitimate forms of knowledge. Yet many migrant teachers resist this framing through what we call Hybrid Professional Becoming. They don’t simply assimilate—they reimagine themselves cosmopolitan teachers of English. They engage in translanguaging, build solidarity, and develop culturally responsive pedagogies.

Natalie, a Bangladeshi teacher, shared:

“Sometimes I switch to English, Chittagonian, Jessore dialect, or what’s called standard or non-standard Bangla—not for fluency, but to build trust. It’s about connection and recognising different ways of knowing”.

Quang, reflecting on his students, said:

“They’d ask me, ‘Is my accent okay?’ I’d say, ‘Your English is beautiful. Don’t worry about it’.”

These teachers are already transforming classrooms

Such affective, relational practices disrupt top-down discourses of “support.” These teachers aren’t waiting to belong—they’re already transforming classrooms.

Yet policy rarely reflects this reality. Instead, it reinforces rigid standards and racialised assumptions. As Anthony Welch notes, fast-tracking applicants from English-dominant nations won’t solve the workforce crisis. Australia must confront the systemic devaluation of those already here.

The AARE Election Statement (2025) calls for equity, multilingualism, and recognition of teaching as a global profession. But first, we must name the problem: Australia’s teaching workforce remains bordered by accent, passport, and memory.

So let’s stop asking whether migrant teachers are “ready for Australia”.

Let’s ask whether Australia is ready to learn from the teachers already here— fluent not only in English, but in empathy, hybridity, and the courage to reimagine education.

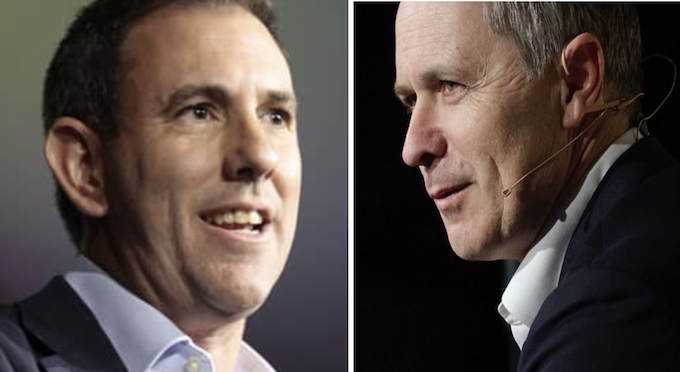

Biographies from left to right

Nashid Nigar teaches at the University of Melbourne and brings 20+ years of experience in language and literacy education, academic writing, and teacher development. Her PhD at Monash Education, awarded the prestigious 2024 Mollie Holman Medal, introduced the framework of Hybrid Professional Becoming—advancing research in multilingual curriculum, teacher identity, and curriculum justice. Her work, grounded in epistemic diversity and equity, informs national policy and supports culturally and linguistically diverse educators globally.

Lilly Yazdanpanah is a lecturer in the School of Education at La Trobe University. Her research focuses on equity and social justice in education, with a particular emphasis on teacher and student identity within English as an Additional Language (EAL) contexts. She has extensive experience teaching in undergraduate and postgraduate teacher education programs across the Middle East, Europe, Central America, and Australia. Before joining La Trobe, she held teaching and research positions at the Faculty of Education, Monash University, specialising in TESOL and General Education.

Sender Dovchin is a Senior Principal Research Fellow and ARC Fellow at Curtin University. Her research focuses on linguistic racism and the empowerment of CALD youth in Australia. She holds a PhD and MA from UTS and serves as Editor-in-Chief of the Australian Review of Applied Linguistics. Recognised as a leading scholar in Language & Linguistics, she has published six books and numerous papers in top international journals.

Rachel Wilson is a leading scholar in education and social impact at the University of Technology Sydney. With a background in psychology, teaching, and research methodology, her work spans education systems, curriculum reform, equity, and leadership. Rachel has extensive experience in research training, educational evaluation, and policy advising, and is committed to advancing quality and justice in education.

Alex Kostogriz is the professor in Languages and TESOL Education within the Faculty of Education at Monash University. He currently serves as the Associate Dean (International) within the faculty. Alex’s ongoing research endeavours are centred around the professional practice and ethics of language teachers, as well as the realms of teacher education and the early experiences of early career educators.