This is the second in a series of posts on education priorities for the 2025 federal election. Today’s posts are about boosting the teacher workforce.

If we’re genuine about addressing the teacher shortage and retaining the excellent teachers we already have in the system – not just recruiting more of the ‘best and brightest’ so we can burn them out – we could start by making the decision to stop infantilizing teachers.

For example, it’s common to read about “teachers being left to fend for themselves” in the classroom because of a lack of standardised curriculum resources that would do the thinking for them and take the load off. It’s a line that dates to a Grattan Institute report from 2022 that’s been taken up with great enthusiasm by some sections of the media (like here and here, and here for the glorious metaphor of “rudderless teachers”, this time attributed to the current Minister himself).

Part of the problem is the disconnect between what the work of the teacher is and what most of the population thinks the work of the teacher is.

We might think that because we went to school, and/or have kids who go to school, that we know what teachers do: the job is to show up at the front of the class from 9am to 3pm every day for a scant 40 weeks a year. Right?

Wrong. That would work if teaching was a performance (although even then they’d presumably need to do a little rehearsal?). But it’s not.

Conditions for learning

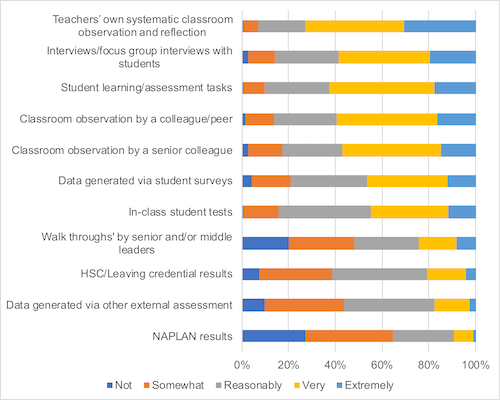

The actual job of the teacher is to create the conditions for learning. For everyone in the class – that’s usually 25 to 30 individuals at a time. To do that effectively, you need to know every one of those students. You need to understand what they bring into the classroom. What they already know. What they’re passionate about. What their strengths are. What they need to work on. Whether they had breakfast this morning. And so on. This is not a newfangled idea: it’s based on decades of research across both psychology and sociology of education.

And that’s what’s wrong with the relentless messaging about how great it would be if all teachers used standardised lesson plans and resources – the so-called “low variance” approach. I’d argue that it’s very last century, but the truth is that the idea of a one-size-fits-all school experience doesn’t just belong in the 20thcentury, it belongs in the dark ages. Anyone who thinks we can standardise our way to an education system that will prepare our young people for the turbulent times they’re going to navigate, hasn’t been paying attention for at least 20 years.

Kids need access to powerful knowledge

And the same is true for the baseless idea that knowledge somehow gets magically transmitted from the brain of the teacher to the brains of students. Kids need access to powerful knowledge, there’s no doubt about that. And they need teachers who can help them learn it, provide feedback along the way when they get things wrong, and drive them to expand and improve in their learning. But we won’t get there with scripted or standardised lessons that spray the classroom with ‘knowledge’ (let’s call it ‘content’) in the hope that some of it will stick.

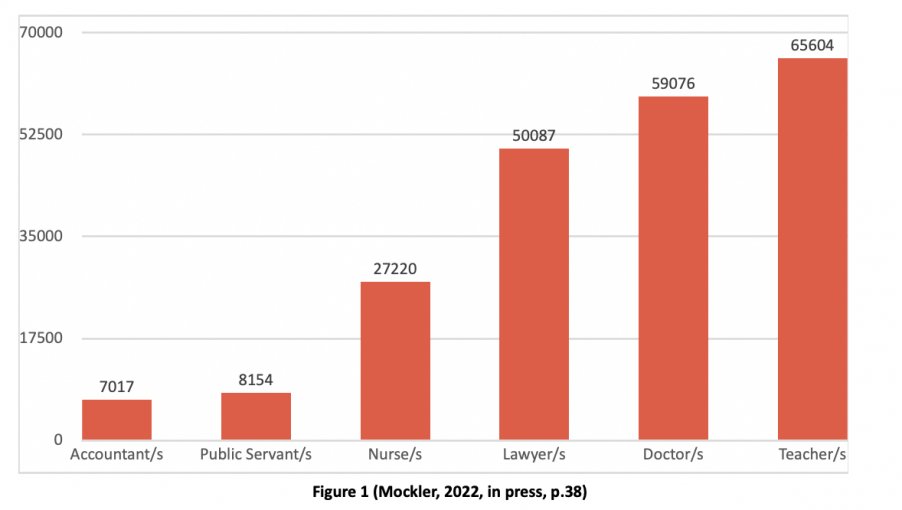

It’s time to recognise that teachers have specialised, professional knowledge that goes beyond what you might have imagined while sitting in a classroom for 13 years. Just like doctors, physiotherapists, lawyers and IT specialists have specialised knowledge that is, effectively, what we pay them for. The difference is that we expect (and hope) that our brain surgeon knows more about brain surgery than we do, while we seem quite comfortable subjecting teachers’ knowledge to some kind of pub test.

Teachers are human

The more we assume that teachers need think tanks or economists or politicians or anyone else to ‘help them fend’, the more it feeds the teacher shortage. Teachers are human. If they don’t feel valued, and are constantly exposed to arguments about their work mounted by people with strong views but next to no actual knowledge of their work, it’s hard to keep showing up.

Respect matters. Valuing what teachers actually know and do, and recognising that it’s complex and that laypeople (and that includes politicians) might not necessarily understand its intricacies would be a pathway to reinstating trust in the teaching profession. And that might just be the perfect place to start in supporting a vital profession in crisis.

Nicole Mockler is professor of education at the Sydney School of Education and Social Work at the University of Sydney and Honorary Research Fellow at the Department of Education, University of Oxford. Her research focuses on education policy, teachers’ work, and education and the media.

Dr Nicole Mockler is an Associate Professor in Education at the University of Sydney. She has a background in secondary school teaching and teacher professional learning. In the past she has held senior leadership roles in secondary schools, and after completing her PhD in Education at the University of Sydney in 2008, she joined the University of Newcastle in 2009, where she was a Senior Lecturer in the School of Education until early 2015. Nicole’s research interests are in education policy and politics, professional learning and curriculum and pedagogy, and she also continues to work with teachers and schools in these areas.

Dr Nicole Mockler is an Associate Professor in Education at the University of Sydney. She has a background in secondary school teaching and teacher professional learning. In the past she has held senior leadership roles in secondary schools, and after completing her PhD in Education at the University of Sydney in 2008, she joined the University of Newcastle in 2009, where she was a Senior Lecturer in the School of Education until early 2015. Nicole’s research interests are in education policy and politics, professional learning and curriculum and pedagogy, and she also continues to work with teachers and schools in these areas.

Nicole Mockler is an Associate Professor in Education at the University of Sydney. She has a background in secondary school teaching and teacher professional learning. In the past she has held senior leadership roles in secondary schools, and after completing her PhD in Education at the University of Sydney in 2008, she joined the University of Newcastle in 2009, where she was a Senior Lecturer in the School of Education until early 2015. Nicole’s research interests are in education policy and politics, professional learning and curriculum and pedagogy, and she also continues to work with teachers and schools in these areas.

Nicole Mockler is an Associate Professor in Education at the University of Sydney. She has a background in secondary school teaching and teacher professional learning. In the past she has held senior leadership roles in secondary schools, and after completing her PhD in Education at the University of Sydney in 2008, she joined the University of Newcastle in 2009, where she was a Senior Lecturer in the School of Education until early 2015. Nicole’s research interests are in education policy and politics, professional learning and curriculum and pedagogy, and she also continues to work with teachers and schools in these areas.