The Australian early childcare sector is experiencing a relentless surge in media attention. It has exposed significant concerns about children’s safety and the quality of early childhood education (ECE) across Australia. Coverage includes multiple and widespread abuse incidents, inappropriate discipline, unsafe sleep practices, serious mistreatment, and seemingly ineffectual regulation.

Evidence from the Early Learning Work Matters project points to systemic issues sitting beneath the diverse array of significant concerns across the Australian ECE sector. In ECE, where educator-child interactions are known to be the most significant contributor to individual child outcomes and service quality, educators’ experiences of work and children’s experiences of ECE are inextricably interwoven.

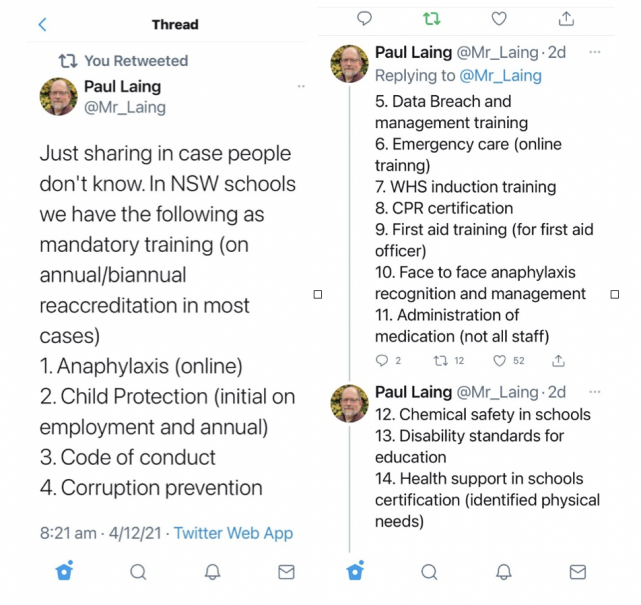

Current concerns around the diminishing quality of educator training programs, increasing casualisation of workforce, along with high turnover rates, attrition, and burnout – are all related to the current concerns around child safety. And yet quality education and care is about so much more than ‘just’ child safety – child safety should be a given.

Early Learning Work Matters

Our latest publication from the Early Learning Work Matters project focuses on educator workload. We surveyed 570 Australian ECE educators. They reported widespread concerns including heavy workloads, particularly non-contact work, regular unpaid hours, and limited and inconsistent access to entitled breaks. Critically, over 70% of educators reported feeling concerned that children are not receiving enough of their time. They also reported that educator workloads in their service are so heavy that they are reducing quality for children. Overall, educators report the nature of their workload and working conditions are reducing their capacity to engage in quality interactions, and to provide a quality program overall.

In the current climate, conditions for both educators and children at large are suboptimal. Genuine and meaningful reform requires thoughtful consideration of the system dynamics that have evolved allowing the current concerning conditions and associated risks to develop.

Systems Theory is an interdisciplinary framework that examines how different parts of a system interact and align to produce outcomes—often in complex, dynamic, and sometimes unintended ways. Rooted in the work of thinkers like Ludwig von Bertalanffy and refined through fields such as ecology, and organisational studies, Systems Theory encourages us to look beyond individual components to understand the interdependencies, feedback loops, and structural conditions that shape behaviours and outcomes.

We need a whole-of-system approach

The diverse concerns evident across ECE in Australia do not need a diverse array of isolated inquiries and solutions. What we need is a whole-of-system approach. That’s an approach where all concerns, such as risks to child safety, heavy workloads for educators and concerns around diminishing quality of educator training, are not separate but treated as facets of the same complex situation.

A key insight from Systems Theory is that elements within a system—people, organisations, regulations, funding flows—respond to the incentives and motivators embedded in the system design. These incentives can be explicit (such as financial rewards or compliance requirements) or implicit (such as reputational pressures). Critically, systems tend to ‘produce what they are designed to produce’. That doesn’t mean they necessarily produce their stated goals, or societal good more broadly. Rather, systems produce what the system design incentivises and promotes.

What’s the big picture?

To understand the ‘big picture’, we first need to ask: what does the current system incentivise and promote? And then critically, how can we shift this, such that quality education and care for young children remains front and centre?

In Australia, where 70% of long day care services are operated by for-profit providers, and 32% are large providers, Systems Theory offers a powerful lens for analysis. When profits and market competition are primary motivators, incentives may prioritise cost efficiency, occupancy rates, and shareholder returns over pedagogical quality or child wellbeing. This can shape service delivery in subtle but systemic ways, for example: limiting educator-child ratios, reducing opportunities for professional development, or skewing investments away from relational, high-quality interactions, toward standardised, scalable models.

As part of an earlier phase of the Early Learning Work Matters project, degree-qualified early childhood teachers were interviewed about their experiences and perspectives of work. Several participants commented on their experience of competing demands, with one sharing: “You’re constantly trying to keep all these different parties happy, and that’s before you even get to the kids, which really should be the number one, but aren’t”.

Not just the experiences of a few

At times like this, it is important to note that these are not just the experiences of a few, these are not isolated concerns. These are representative of system issues underpinning the sector at large.

A systems-informed analysis does not simply criticise individual providers but interrogates how regulatory settings, funding mechanisms, workforce conditions, and market structures interact to produce current patterns of care. It asks: what and who does the system currently reward, and what or who is neglected? Further, what are the system goals and how are other system elements aligned with them? Crucially for ECE, a systems-informed analysis should ask: what kind of system design do we need to ensure that the best interests of young children—rather than commercial returns—are the driving force of early education provision?

Understanding and applying Systems Theory in this way helps shift the focus. It shifts the focus from symptoms to structures, and from individual cases with isolated interventions to meaningful systemic change.

No more reactive policy

How can we do this? We need more reporting transparency. And we need more largescale data and more quality research. That’s to better understand the scope and complexity of issues we are now facing. We must give voice to our educators — they are the ones on the ground working in this system day-by-day. We need to understand the complexity of the issues our educators are experiencing. And finally, we need to take a big picture perspective to understand our ECE system in its entirety.

No more reactive policy. No more band aid solutions, and knee-jerk reactions. A coordinated and cohesive approach to system design is needed. We need that to safeguard children’s wellbeing at a minimum — and beyond that, to support every young child to flourish and thrive.

Erin is a Lecturer in Early Childhood Education at the University of Sydney, and an early childhood teacher, with a Bachelor of Education and over 15 years working with children from birth to five years of age.

Rachel is Professor of Social Impact at the University of Technology Sydney and an internationally recognised expert in education. She has a long track record of diverse social science research looking at education, work, health, management, leadership, and broader human development.