03 February 2025, Canberra, ACT: The Isolated Children’s Parents’ Association (ICPA) Australia is

calling on the Federal Government to commit to critical funding increases and new support

measures to ensure equitable education access for geographically isolated students. ICPA Australia

says rural and remote families are being left behind by an outdated education support system that

fails to keep pace with rising costs and increasing needs.

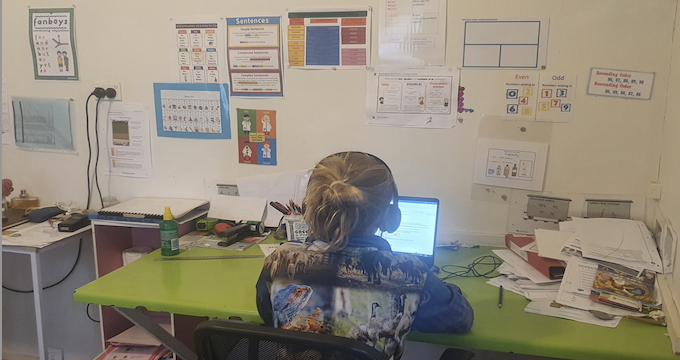

Karen Peel and Patrick Danaher reveal what they have learned about distance schooling in Australia.

Thousands of children learn remotely in Australia.

And fundamental to the delivery of distance schooling is the commitment of what we call the remote education tutor (RET) who functions as a conduit between the distance schooling teacher and the student.

Our research shows that the requirement of providing a supervisor in the remote schoolrooms is creating a sense of educational marginalisation. This can particularly impact on mothers, who are often expected to be the support providers for their children with no remuneration.

The work of the RET is essential for quality and equitable education for children living in these distant locations.

But we treat RETs and say, for example, teachers’ aides, very differently.

The equivalent roles of RETs and teacher aides

Let’s compare the support offered to distance education students by the RET with the work of teacher aides employed to assist in general schooling classrooms in Australia. Over the past four decades, schools increased the number of teacher aides employed, to assist teachers in providing quality education for students.

That’s exactly what RETs do. Unlike RETs, teacher aides get paid.

There is the direct comparison which reveals the inequality in distance schooling and the significant cost, both personally and financially, to geographically isolated families.

So how did we get to this?

Who performs the role of the RET in Australian distance schooling?

Research tells us there are two distinct groups of RETs: governesses, who are employed as RETs in a paid position; and mothers, who facilitate their own children’s education in the home schoolroom.

Governesses cost a fortune and – often with limited or no training – they learn on the job.

For many geographically isolated families, meeting the cost of employing an RET is not a reality. As such, mothers are left with restricted rights and few choices. Moreover, they receive no income for completing the complex role of the RET, and limited acknowledgement for undertaking this essential and mandated educational position.

Acknowledgement and remuneration for the RET

The parents who attended the 2024 Queensland Isolated Children’s Parents’ Association (ICPA) conference conducted in Townsville, Australia unanimously voted for a proposal to provide suitable acknowledgement and remuneration for RETs. The same proposal was met with the same enthusiasm 50 years previously.

So why hasn’t the move for educational equality for families living in geographically isolated locations gained traction? Could it be that mothers are just expected to make sacrifices?

The mother as the RET

States and territories mandate that students 12 years and under must be supervised by an adult for the whole school day. And mothers do that while also juggling with other responsibilities and the management of this substantial and time-consuming task.

Compare that to the mothers of children beginning mainstream schooling. There are opportunities for them to return to paid employment and contribute to the family income. Mothers in geographically isolated locations don’t have that option. They have to undertake the role of the RET. These duties can extend for several years, depending on the number of children in the family.

Groups such as the ICPA repeatedly advocate for the role that rural women play in educating their children. But politicians – and the rest of us – should be forced to acknowledge how hard it is to access compulsory education for families living in geographically isolated locations.

Researching mothers as RETs in Australian distance schooling

We wanted to know how mothers felt about their roles as RETs.

Here’s what we found. They positioned themselves dutifully to meet the demands of their dual identities. They understood that where they lived created the need to educate their child/ren through distance schooling.

But they were all aware of the comparison between the equitable rights of mainstream schooling and those of distance education.

One mother/RET pointed out the inequities and financial burdens of being positioned to fulfil the RET role. She said, “Because we are geographically isolated, me doing this role is our only choice unless we want to send our kids to boarding school, which costs a lot of money.”

Another mother/RET was critical of the perceived inequity of financing the work of teacher aides in the mainstream schooling without there being an equivalent commitment to financing the work of the RET.

However, there was acceptance by the mothers of their duties as RETs, accompanied by a sense of responsibility. They recognised the significance of their role for their child/ren’s education.

This was clearly articulated in the statement: “I taught all my kids to read. A half an hour lesson with a teacher online isn’t going to teach a kid to read.” Much of the responsibility for teaching reading goes well beyond the limited time available in the online lessons with the school-based distance education teacher.

Another mother/RET made it clear that she “is not a teacher but is willing to learn how to provide the very best start for [her] child’s education”. She identified her RET position as a “duty of care”, and herself as a “volunteer” performing “a hugely underestimated role”.

What is the role of the RET?

Substantially, the lack of understanding and underestimation of what the RETs’ role entails are of concern.

One mother/RET proudly lamented, “I think I have done a pretty good job with the kids, but it’s that lack of value and recognition”.

What was especially significant in this research were the challenges for the mothers performing the dual roles of being the caregiver and the RET. This tension cannot be overestimated.

One mother/RET admitted, “I do struggle and think that, if you were just the teacher, you’d be a little bit more patient, whereas being the mother as well, it definitely blurs.”

Recognising the dual identities of mothers as RETs

Recognition of the dual identities of the mothers as RETs, who facilitate their child/ren’s successful learning outcomes, affirms this substantive position. Our research underscores the importance of establishing a system of government support for financial compensation so this work can extend to being more than a labour of love.

Karen Peel is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Education at the University of Southern Queensland, Australia. She is an experienced classroom teacher having taught in Australian schools across decades of educational transformations. Her research interests include the implementation of practices for effective teaching and self-regulated learning, classrooms cultures that support positive behaviour and contemporary issues in education that impact outcomes for students and educators. She is on LinkedIn.

Patrick Danaher is Professor in the School of Education at Excelsia University College, and Professor Emeritus at the University of Southern Queensland, Australia. Patrick has continuing research interests in rural education, including the educational aspirations and outcomes of occupationally mobile families such as circus and show people who travel through regional, rural and remote communities. More broadly, he is interested in formal education’s ambivalent capacity to perpetuate sociocultural marginalisation and to contribute to sociocultural transformation. He is on LinkedIn.