Complex trauma is increasingly recognised as a hidden epidemic. It is estimated that one in four Australians suffer the effects of complex trauma. In response, the application of trauma approaches has expanded significantly across school settings. Advice about how to respond to trauma in school classrooms is available. However, when it comes to higher education, we’re only just beginning to catch up, underlining the need for a better understanding of this area.

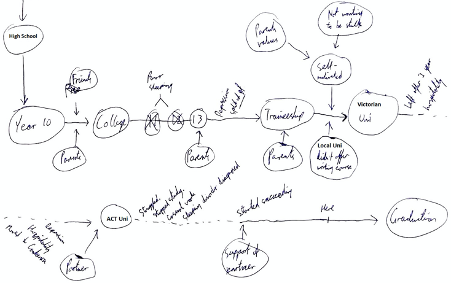

Many students bring complex trauma into their university experience. For some, this trauma is linked to earlier life experiences such as abuse, loss of family members, systemic disadvantage or time in care. For others, it’s the experience of university itself that can cause or compound harm. Unclear processes, inflexible assessments, and a lack of cultural safety can all affect student wellbeing in ways that aren’t always recognised. These may intersect with other on-campus sources of trauma, such as the high rates of sexual violence on campus.

Not just distress

This is not just a matter of individual distress, it’s a matter of equity. Students affected by trauma are more likely to be members of communities already identified by universities as priorities for inclusion and support. These include those from low-income backgrounds, First Nations students, disabled students, LGBTQ+ students, and refugee-status backgrounds, among others.

Trauma awareness in higher education is important for at least four reasons.

- To enhance learning outcomes, creating environments where all students can engage more effectively.

- To prevent re-traumatisation by recognising and reducing unintentional harm.

- To support equity for students navigating trauma alongside their studies.

To fulfil social responsibility by understanding and working to reduce the social conditions from which trauma originates.

Trauma-informed teaching and mental health services are vital but fulfilling social responsibility also demands action. Universities’ research expertise and community influence place them in a unique and powerful position to examine the structural factors that create trauma. These include poverty, discrimination and institutional violence, and to advocate for systemic changes that address root causes rather than simply managing consequences.

Trauma is both a personal experience and a social phenomenon

Most discussions of trauma in higher education rely on clinical understandings. While useful, these approaches come from specific cultural and historical contexts. Cultural historian Ruth Leys reminds us that trauma is not a fixed concept. Its meaning has changed over time—from moral injury to psychological shock, to neurobiological response. These shifts are shaped by history, culture, and politics. In education, we need to be mindful of which versions of trauma we rely on, and what they might leave out.

Indigenous scholars in Australia and internationally offer sophisticated understandings. These perspectives emphasise collective and intergenerational trauma, and recognise how ongoing systems such as colonisation, racism, and dispossession contribute to harm. For these thinkers, trauma isn’t always a past event. It’s a present reality. However, resilience and healing are also emphasised. Such perspectives can expand how we think about student wellbeing and what it means to create safe and inclusive learning spaces.

Importantly, responding to trauma is not just the job of counsellors or academic staff. Every person who interacts with students has a role to play, from tutors and supervisors to front-desk staff and senior leaders. A ‘whole of university’ perspective foregrounds the need for deep reflection about how systems, language, and everyday practices within the academy may impact students. These are students who are already doing their best to manage difficult circumstances.

Listening, not assuming

In our own conversations with students and educators, we’ve heard how trauma can impact concentration, relationships, assessment navigation, and more. We have begun to think of the impacts of trauma as an overlooked aspect of intersectionality, which can imbricate other minority positions and disadvantages. For instance, when students struggle to access support designed specifically for them, this can heighten distress and create a secondary trauma that damages trust in institutions.

Yet, especially when trauma experiences or inequities are not disclosed or known, what helps is not always more support, but more flexibility. Trauma-informed practice can’t be one-size-fits-all. Instead, this approach needs to be adaptable, attentive, and rooted in the realities of student experience. Adopting a critical stance that deliberately questions ‘taken for granted’ approaches or perspectives can also help us begin to unpack what may be deeply unsettling expectations and practices for some students.

Help shape a better future for students

Our team has recently begun a new research project. It focuses on trauma awareness in higher education. We want to understand how student trauma shows up in university spaces. And we also want to know how institutions might respond in ways that are more equitable, inclusive, and supportive. We intend to benchmark understandings of trauma across members of the higher education community. We’ll use this knowledge to create practical initiatives grounded within higher education realities.

If you work in Australian higher education and are interested in participating, you can find out more about the project here.

Sarah O’Shea is lead investigator in the Higher Education Equity Research Unit and Maree Martinussen is a researcher in social class and higher education equity , both at Charles Sturt University.