When it comes to new teachers, there is an expectation that they are “classroom ready” from day one on the job.

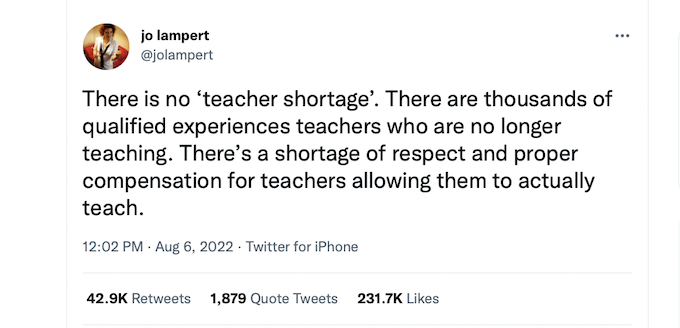

Yet there is mounting evidence that new teachers are being sent into schools that are short-staffed and where experienced teachers are leaving the profession, feeling high levels of stress and burn out.

Clearly, even at the best of times, teaching is a complex profession. Developing proficiency to work in this kind of context requires time, experience, and supported opportunities for feedback and reflection.

“Classroom readiness” has become a buzzword in education policy and teacher education; all initial teacher education providers need to assess graduates’ readiness through Teaching Performance Assessments.

Given that it is so challenging to create workplaces that keep experienced teachers in the profession, our research looked at these expectations of new teachers. We conducted a scoping review to examine what ‘classroom readiness’ means, and whether or not it can – or should – be assessed.

Assessing new teachers’ classroom readiness

We found that classroom readiness is conceptualised in three broad ways: as adherence to a set of regulations and standards; as a policy construct; and as a professional journey.

Given the requirement that all initial education providers assess pre-service teachers through Teaching Performance Assessments according to teacher professional standards, it is not surprising that much of the literature defines classroom readiness according to these standards. There has been an ongoing discussion about the suitability of this approach for some time. Back in 2009, Connell described teacher standards this way:

What teachers do is decomposed into specific, auditable competencies and performances. The framework is not only specified in managerialist language. It embeds an individualised model of the teacher that is deeply problematic for a public education system. The arbitrariness of the dot-point lists means that any attempt to enforce them, on the practice of teachers or on teacher education programmes, will mean an arbitrary narrowing of practice. (p. 220)

As a policy construct, classroom readiness is used by governments and regulatory bodies to justify reforms in teacher education, and to reassure the public that teacher educators are held to high standards. This approach has seen initial teacher education providers absorb the high costs associated with implementing and moderating teaching performance assessments.

Finally, others describe readiness as an ongoing journey of growth and development rather than a fixed state that can be measured at a single point in time. Even the best beginning teachers continue to learn and adapt as they encounter new challenges and contexts. This view argues that they should not be expected to be fully prepared from the start. Authors in this final group instead advocate for adequate recognition of the complex and relational aspects of teaching that cannot be assessed in a TPA.

The problem with “readiness”

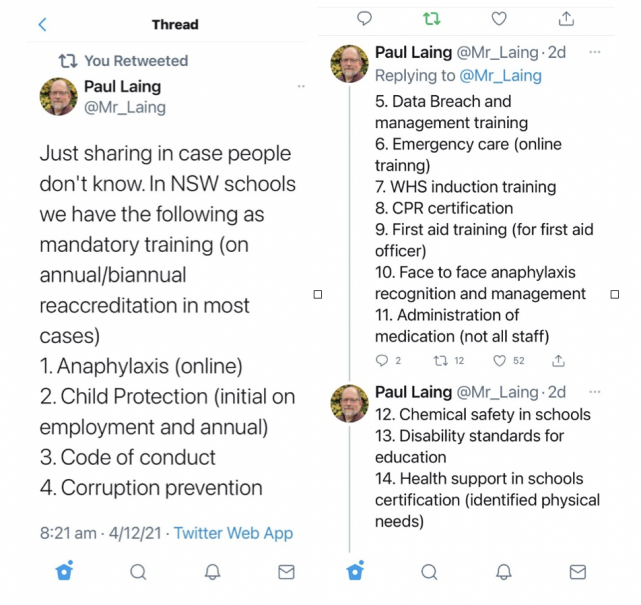

The first problem with the rhetoric of ‘readiness’ is that it has the potential to place unrealistic expectations on beginning teachers. Assessing readiness through a narrow lens that has a focus on planning, teaching, assessment and reflection has the potential to gloss over the support that new teachers really need.

Teachers’ work is primarily relational in nature and measuring classroom readiness overlooks aspects of teaching that are hard to quantify, but yet are foundational for teaching and learning. Teaching is complex and one assessment cannot capture the diverse contexts and level of adaptability and resilience required of beginning teachers.

The second problem with readiness is that there is no agreement across the literature, or even in policy itself, about how it could be possible to assess whether a new teacher can do everything from supporting students experiencing complex trauma, through to managing excessive workloads. The OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 indicates that Australian teachers report higher levels of stress than the OECD average and that 30% to 50% of all teachers leave the profession in the first five years. This is the context into which new teachers find themselves. A serious question is whether it is realistic for anyone to be ‘ready’ for these circumstances; and if so, how it would be possible to assess readiness to work in these conditions.

It takes a system to support beginning teachers

It is not realistic to expect that just because new teachers can plan and teach a lesson during a supervised placement, they are fully prepared for the complex schools where they are likely to work. In fact, expecting beginning teachers to work independently from day one, without sufficient ongoing mentoring, risks reinforcing the very conditions that push more experienced teachers out of the profession.

It is undoubtedly important that ITE programs equip pre-service teachers with strong understandings of curriculum and assessment, teaching practices, and student diversity. However, if we want beginning teachers to have long and rewarding careers, they must be met with appropriate support once they enter the profession. Recent research shows that beginning teachers need support that is specific to their context, which requires sustained government investment.

This is not to say there are any easy solutions for how to support new teachers. Experienced teachers are already operating at their limits, particularly in hard-to-staff schools where teacher shortages and turnover have substantially increased the workload of experienced teachers. Without adequate resourcing for time release, reduced teaching loads, professional development and networking, mentor teachers themselves risk burnout, further compromising the support new teachers need.

It is understandable that policy makers and systems want assurance that new teachers are ready to tackle the demands of the job from day one. However, the real-world complexities of teaching mean that no amount of preservice teacher preparation can full equip graduates for every situation they will encounter. What beginning teachers need are fair workloads, ongoing mentoring, opportunities for collaboration, and access to professional learning that is responsive to the evolving demands of their specific school context.

A professional journey of growth

Rather than viewing classroom readiness around a set of standards to be achieved by the end of a degree, we should view it as the beginning of a professional journey of growth. New teachers require time, support, mentorship and opportunities to reflect and learn as they navigate the demands of their early years in the classroom.

Nerida Spina is an associate professor at the Queensland University of Technology in Australia. Nerida’s research expertise is teaching and leadership for equity and social justice. Rebecca Spooner-Lane is an associate professor at the Queensland University of Technology. Her research explores the professional development and career progression of teachers from graduate to lead teacher. You can find her on LinkedIn. Elizabeth Briant is an associate lecturer at the Queensland University of Technology. Her research explores contemporary social conditions that shape the growing use of private tutoring in Australia. Julia Mascadri is a senior lecturer at the Queensland University of Technology. Her research interests include pedagogical practice in early childhood education, educational leadership, and assessment in initial teacher education. You can find her on LinkedIn