Federal Education Minister Jason Clare has unveiled the biggest shake-up in schooling policy in decades, announcing plans to merge four national education agencies—ACARA, AITSL, AERO, and ESA—into a single Teaching and Learning Commission (TLC). The idea is to bring core areas of curriculum, assessment, reporting, teaching standards, research, technology and data under one roof, rather than leaving them fragmented across multiple bodies.

Clare’s agenda is ambitious. At a speech delivered this week, he presented the TLC as a bold and targeted solution to Australian education’s most troubling challenges, including declining Year 12 completion rates, underperformance in disadvantaged communities and deeply entrenched inequities.

He shone a bright light on public schools, highlighting that the proportion of students completing Year 12 has fallen “from about 83 percent to as low as 73 percent” over the past decade. By contrast, completion rates in Catholic and Independent schools have remained high and stable. Public schools, Clare argued, “play an outsized role in educating some of the most disadvantaged children” and must be at the centre of efforts to lift outcomes and close equity gaps.

The proposed TLC is designed to align with the Better and Fairer Schools Agreement (BFSA), the new 10-year national funding deal (2025–2034) signed between the federal government and all states and territories. Clare described the BFSA as “a $16 billion investment” that commits all governments to lift outcomes and tackle inequity.

The BFSA includes a suite of reforms and targets designed to lift student performance, address student wellbeing and mental health, attract and retain teachers, tackle inequalities and improve access to evidence-based professional learning and curriculum resources.

Not exactly a surprise

As bold as this looks, the TLC idea is not entirely new. As David de Carvalho, former ACARA Chief Executive Officer, pointed out this week, the writing has been on the wall for years.

Debate about the suitability of the “national architecture” of Australian schooling has been long-standing. The potential for agency mergers was raised explicitly in the 2019 Review of the National Architecture for Schooling in Australia, led by Simone Webbe. While that review stopped short of recommending one single body, it did explore merging ACARA and AITSL. Ministers showed little appetite for such structural change at the time, but the idea lived on in policy backrooms.

When I conducted research for my book The Quest for Revolution in Australian Schooling Policy, I interviewed more than 80 senior policymakers. Many were deeply dissatisfied with the existing national machinery, describing it as fragmented, duplicative and incoherent. They spoke of blurred responsibilities, overlapping mandates, and uneven power relations when federal, national and state agencies jostle for influence.

I am now conducting another round of interviews with senior policymakers as part of a new project funded by the Australian Research Council, and the same themes keep repeating. Australia has developed a patchwork of multiple national agencies tasked with different aspects of schooling, but it lacks a coherent forum capable of strategically steering the system as a whole. This absence of a national compass for long-term policy design and coordination is precisely what Clare’s proposal seeks to address.

The landslide victory of the Albanese government has created a rare window for bold reform. The TLC proposal comes at a moment where dissatisfaction with existing arrangements, the promise of new policy solutions and favourable political conditions have converged to make once-unlikely changes possible.

But is it a good idea?

For decades it has become increasingly difficult to see “who is steering the ship” of Australian schooling policy. While federal influence has rapidly expanded, so have national organisations that have varying relationships to Australian jurisdictions and schooling sectors.

Greater national coherence through a TLC could help provide some clarity. But there is also a dangerous flipside.

Diversity across our federation has long acted as a safeguard against over-centralisation and the domination of short-term political agendas. The fact that states and territories retain the constitutional authority to govern schools is at the very core of what it means to be a federation. It ensures that no single level of government can fully dominate and that local contexts and sectoral priorities have legitimate roles in shaping education.

In his classic text Seeing Like a State, anthropologist James Scott provides a compelling set of historical evidence to show the issues that emerge when humans seek to homogenise systems. Scott shows that while the logic of standardisation seems to make sense—because in theory it allows for greater control over inputs and outputs—reality always bites back.

This is the double-edged nature of the TLC proposal. If it delivers, then equity and performance across our schools may finally improve. But if its policies fail, the whole system will feel the impact. In a federated model, policy missteps can often be contained within jurisdictions. In a more national model, the whole nation is at risk.

A real danger lies in assuming neat designs from above can steer the realities on the ground. Perhaps, in this moment, the government would do well to remember the advice of another TLC (the 1990s R&B pop group): “don’t go chasing waterfalls” and “stick to the rivers and the lakes that you’re used to”—unless, of course, they’re absolutely sure the system is ready for the plunge.

Oh, and then there’s politics

On paper, the political logic behind the TLC is easy to grasp. Clare will have a compelling argument to make to state and territory ministers when they next meet at the Education Ministers Meeting (EMM). A streamlined agency promises national leadership, coherence, less duplication and greater accountability. It also allows Clare to show his government is prepared to be bold on education reform.

Even if ministers agree to progress the TLC, the politics of implementation will be fraught. While Canberra funds schools generously, it does not run them. Schooling is constitutionally the responsibility of the states and territories, and any reform that muddies this division of roles is bound to be politically difficult. Moreover, states and territories rarely speak with one voice, and even when they do, they approach these debates with different histories and vested interests.

The influence states can exert over national agencies is also a major point of debate. The governance of ACARA and AITSL provides an important precedent. When ACARA was established in 2008, it was set up as a co-owned body, with state and territory ministers given the right to nominate board members. Catholic and Independent schooling sectors were also granted representation.

AITSL, by contrast, is a Commonwealth-owned company with an independent board of experts rather than jurisdictional nominees.

These contrasting models highlight the delicate politics of shared authority and the constant negotiation required between federal, state, territory and sectoral interests.

A key question is what the governance structure of the TLC will be. Will states retain nomination rights, as with ACARA, or will expertise be privileged over representation, as with AITSL? And what role will Catholic and Independent representatives have at the decision-making table?

These are delicate politics to navigate, and if ministers or sector representatives feel their role in steering national education is weakened, resistance will be fierce.

The stakes are high

The Albanese government has the mandate, the means, the resources, and the political capital to drive major change in Australian schooling. And the problems to tackle are real.

Falling Year 12 completion rates, entrenched disadvantage in public schools, teacher shortages, flat results, and declining student engagement are all urgent and pressing. As Minister, why wouldn’t Clare seek to tackle them head on?

Yet more money, new targets and a super agency will not be enough to turn the tide. Reform must also build cultures of collaboration, trust and professional engagement within schools. History shows that reforms which sideline the professional wisdom of teachers rarely produce lasting improvement. If the TLC is to succeed, the teaching profession cannot be an afterthought: it must be in the driver’s seat.

For decades, the default formula of Australian governments has been to set tighter targets and impose more top-down directives. There is little evidence this approach delivers sustained gains.

Regardless of whether the TLC succeeds or fails, it represents another step in a decades-long shift towards federally driven national reform. Any federalism scholar will tell you this runs counter to the principles of federalism and the benefits of subsidiarity.

The creation of a TLC is being sold as a solution. It may well become the foundation of meaningful reform. But it could just as easily centralise risk in ways that make the system more fragile rather than more resilient.

Jason Clare’s gamble is clear. If the TLC works, it could be the engine of a new era in schooling reform. If it sinks, the whole ship goes down with it.

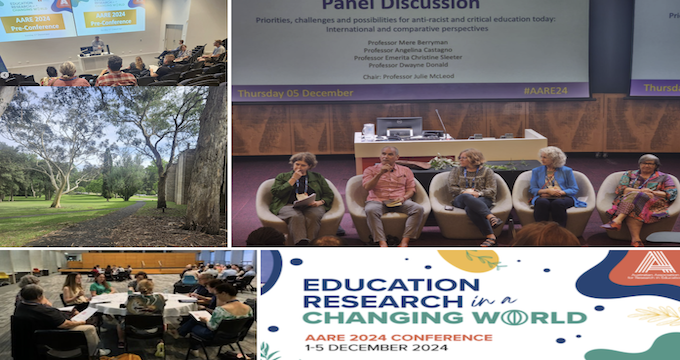

Images of Jason Clare from his Facebook page.