Around the world nations have experienced significant growth in their immigrant populations, including an increase in immigrant students. The way schools respond to this has a significant impact on how well immigrant students adapt to and succeed in school.

Although there are many success stories, there are also immigrant students who struggle at school. They are then at risk of missing out on vital educational and job opportunities after school. This impacts individual students as personal potential is unrealised. It also impacts at the national level because immigrants have and always will be a key part of nations’ social and economic development.

We need to understand how to support immigrant students in overcoming academic challenges and supporting their educational wellbeing.

Our study

In a recent research study published in the Journal of Educational Psychology, we harnessed the Academic and Cultural Demands-Resources (ACD-R) framework to investigate the factors that are important for nurturing immigrant students’ academic motivation and achievement. We used the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) data from Australia and New Zealand—two countries with a history of receiving migrants to live and raise their families. PISA is a worldwide study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of 15-year-old school students’ learning and performance in mathematics, science, and reading.

Two main parts of PISA are a student survey and a school leader survey. In a previous study, we focused on the student survey and how teachers can support individual immigrant students. This present study focused on the school leader survey and how whole-school action can support immigrant students.

The ACD-R Framework

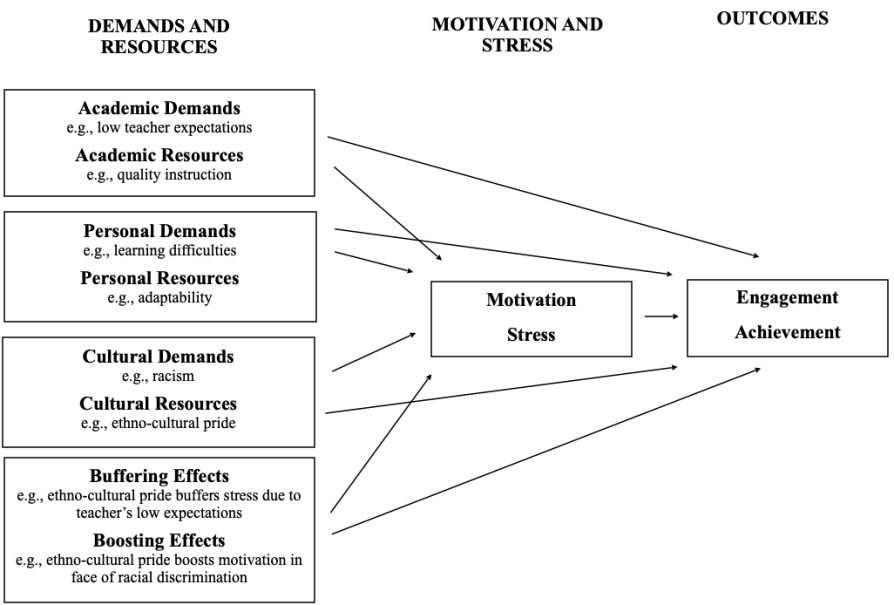

Under the ACD-R framework, demands are features of the learning process or learning environment that can get in the way of students’ educational progress – while resources help and support students’ educational development. These demands and resources may be academic factors or ethno-cultural factors that impede or assist students’ educational pathways.

Participants in Our Research

The research involved 545 schools across Australia and New Zealand) and nearly 5000 immigrant students.

The school leaders were asked to report on key features of their school, including the various demands and resources present in the school. We then linked their responses to the motivation and achievement scores of the immigrant students in their school (summarized from the PISA student survey). This enabled us to examine the whole-school factors that are associated with the academic development of immigrant students in the school.

The Measures in Our Study

The main measures in our research were drawn from survey items administered to school leaders asking about the academic and cultural demands and resources in their school. Academic demands were assessed via two measures. The first tapped into the extent to which school instruction was hindered by staffing and resourcing issues, what we call a resource shortage. The second asked about the extent to which students’ learning was hindered by the nature of teaching (e.g., teachers not meeting individual students’ needs), referred to as hindered learning. Academic resources were assessed with a measure which asked about the extent to which students were provided with resources to support their learning, referred to as student assistance (e.g., rooms where students can do their homework).

Cultural demands are represented by immigrant socio-economic disadvantage. This refers to the proportion of immigrant students in a school experiencing socio-economic disadvantage. Cultural resources comprised cultural learning, shared cultural values and immigrant student language support.

Motivation was assessed through measures of self-efficacy (students’ belief in their capacity to attain desired academic outcomes) and valuing (their belief in the usefulness and importance of what they learn).

Achievement was based on students’ achievement on the PISA mathematics, science, and reading tests.

In all our analyses we accounted (controlled) for school location, school type (non-independent, independent), staff/student ratio, average class size, and percentage of immigrant students in the school—so we knew that any significant demand and resource findings were above and beyond any influence due to school location, etc.

Our results

The study identified four demands and resources that were significantly associated with immigrant students’ motivation and achievement:

- Student assistance and cultural learning (academic and cultural resources) that had positive effects.

- Resource shortage and immigrant student socio-economic disadvantage (academic and cultural demands) that had negative effects

In addition to these significant demands and resources, we also found immigrant students’ motivation was significantly linked to their academic achievement. Immigrant students who believed in themselves (self-efficacy) and saw the relevance, importance, and usefulness of school (valuing) were likely to achieve highly.

Strategies for Schools

These findings point to six areas of whole-school action, each attending to a significant demand, resource, or motivation factor in the study.

- Resource shortage (academic demand). Our study signalled various aspects of school-level resource shortages that need attention when supporting immigrant students, including inadequate teaching- and learning-related infrastructure (e.g., teacher shortages) and a lack of educational materials, resources, and learning spaces.

- Student assistance (academic resource). At the same time, we found academic resources in the form of student assistance played a supportive role for immigrant students. Our study indicated such resources include provision of staff to help with homework and study, practical help and relational support from teachers that help immigrant students develop their academic skills and provide a sense of belonging at school.

- Immigrant socio-economic disadvantage (cultural demand). Schools may look to target the barriers that disadvantaged immigrant families can experience if they are socio-economically disadvantaged. In our research, we identified “agency” as one factor and suggested schools can work with immigrant parents and ethnic communities to design and implement linguistically and culturally responsive interventions (e.g., authentic school involvement of immigrant students’ cultural community) to empower families in the process of supporting immigrant students, especially those that have newly arrived to the country.

- Cultural learning (cultural resource). Promoting this involves schools fostering learning about diverse cultures and the histories of these cultures. This can be strengthened through curriculum that provides a nuanced and authentic representation of diverse ethnic and cultural groups both locally and globally.

- Self-efficacy (motivation). Boosting students’ self-efficacy can involve teachers breaking schoolwork down into manageable chunks for students to experience smaller successes as they learn (this builds confidence through tasks), encouraging students to recognize their academic strengths (that also builds academic confidence), and teach students how to challenge negative beliefs that may be undermining their self-confidence.

- Valuing (motivation). There are three types of valuing that can be nurtured. The first is attainment value, which involves explaining to students how what they learn at school is important. The second is intrinsic value, which involves setting schoolwork that arouses curiosity or is enjoyable. The third is utility value, which involves making it clear to students how what they learn is relevant to their lives or to the world more broadly.

Our research shows how to implement whole-school action to support immigrant student cohorts. The findings demonstrate that attending to cultural demands and resources, alongside academic factors, has significant potential for optimising immigrant students’ educational development through school and beyond.

Andrew Martin is Scientia Professor of Educational Psychology and chair of the Educational Psychology Research Group, School of Education at UNSW. He specialises in student motivation, engagement, learning, achievement, and quantitative research methods. Gregory Arief D. Liem is associate professor in the Psychology and Child & Human Development Academic Group at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His research focuses on student motivation and engagement. Rebecca Collie is Scientia Associate Professor in Educational and Developmental Psychology at UNSW. Her research interests focus on motivation and well-being among students and teachers, psychosocial experiences at school, and quantitative research methods. Lars Erik-Malmberg is professor in education at the University of Oxford. His research interests are in quantitative research methods and students’ academic development. Tim Mainhard is professor of educational sciences at the University of Leiden. His research interests are in teacher-student interactions, student motivation, learning, and wellbeing.